INTRODUCTION

The printing press is considered one of the most important inventions in history. This device has made it possible for books, newspapers, magazines, and other reading materials to be produced in great numbers, and it plays an important role in promoting literacy among the masses.

It was developed based on early principles of printing, and it has undergone many modifications over the years to meet the needs of people in different eras. The earliest documented evidence of printing dates back to the 2nd century when the ancient Chinese started using wooden blocks to transfer images of flowers on silk. Around the 4th century, woodblock printing on cloth was practiced in Roman Egypt. The Chinese began printing on paper in the 7th century, and they created the Diamond Sutra, the first complete printed book, in 868.

The first movable type printing system was invented by Pi Sheng in China around 1040. This printing device used movable metal type pieces to produce prints, and it made the process of printing more efficient and flexible. Nonetheless, since it was made of clay, it broke easily.

In the 13th century, the Koreans created a metal type movable printing device, which applied the typecasting method that was used in coin casting. By mid-15th century, a number of print masters in Europe were getting closer to perfecting movable metal type printing techniques, and one of them was Johannes Gutenberg, a former goldsmith and stone cutter from Mainz, Germany.

Gutenberg created an alloy that was made up of tin, lead, and antinomy. This alloy melted at low temperature, and it was excellent for die casting and durable in the printing press. It made it possible for separate type pieces to be used and reused. Instead of carving entire words and phrases, Gutenberg carved the mirror images of individual letters on a small block. The letters could be moved easily and arranged to form words. This device was the printing press, and it revolutionized the printing industry.

Gutenberg created an alloy that was made up of tin, lead, and antinomy. This alloy melted at low temperature, and it was excellent for die casting and durable in the printing press. It made it possible for separate type pieces to be used and reused. Instead of carving entire words and phrases, Gutenberg carved the mirror images of individual letters on a small block. The letters could be moved easily and arranged to form words. This device was the printing press, and it revolutionized the printing industry.

In 1452, Gutenberg started printing his most famous project, the Gutenberg Bible. He managed to produce a total of two hundred copies of the bible, and he offered them for sale at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 1455. Gutenberg’s printing press led to a dramatic increase in the number of print shops throughout Europe.

Nonetheless, as the demand for printed materials increased over time, there was a need for a printing press that could produce higher quality prints at a faster rate. In the year 1800, Earl Stanhope from England invented a cast-iron printing press that was capable of producing cleaner and more vivid impressions. Other inventions that followed included the Columbian press, bed-and-platen press, cylinder press, rotary press, Bullock press, linotype machine, and monotype machine.

Today, printing is mostly done with the use of computers, and modern printing devices can produce prints at a much faster rate than those that were used in the past. More printing is done in one second today than in a year during the 15th and 16th centuries. In fact, modern technology has made it possible to print and deliver the printed material in less than twenty for hours. Overnight printing has become widespread and even expected, especially amongst hurried executives needing fast business cards, brochures, and other overnight printing services.

PRINTING TODAY

Today, printing is very different from the process used in Gutenberg’s workshop. By modern standards, Gutenberg’s printing process may seem slow and tedious; compositors put type together by hand, and a skilled compositor could assemble 2,000 characters or letters in an hour. A computer can arrange the same number of characters in about two seconds.

Today, more words are being printed every second than were printed every year during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Today, more words are being printed every second than were printed every year during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Until the nineteenth century, printers completed each step of printing by hand, just as they did in Gutenberg’s printshop. As technology evolved, inventors adapted these new technologies to revolutionize printing. Steam engines and, later, electrical engines were incorporated into the design of printing presses. In the 1970s, computers were integrated into the printing The Printing Press Gets Recast in Cast Iron In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, inventors began modifying the printing press by making parts of the press out of metal instead of wood.

Earl Stanhope of England created a printing press with a cast-iron frame. In 1800, he invented the Stanhope Press, which was the first book press made completely out of cast-iron. The press also featured a combination of levers to give the pressman added power. It created powerful, cleaner impressions, which were ideal for printing woodcuts and larger formats.

The Columbian Press, invented in 1816 by George Clymer of Philadelphia, was also an iron hand press. It could print 250 copies per hour. The press was noteworthy because it used a series of weights and counterweights, making it relatively easy for the printer to increase the force of the impression and raise the platen after each impression. The eagle mounted on the top of the press served as both a patriotic symbol and a counterweight. Like Gutenberg’s press, these platen presses had a flat surface bearing the paper, which was pressed against the flat-inked plate.

Newspaper and magazine presses were often large, specially constructed machines that would produce many copies as quickly as possible. Mechanized Presses In 1824, Daniel Treadwell of Boston first attempted to mechanize printing. By adding gears and power to a wooden-framed platen press, the bed-and-platen press was four times faster than a handpress. This type of press was used throughout the nineteenth century and produced high-quality prints.

In 1812, Friedrik Koenig invented the steam-driven printing process and dramatically sped up printing. The Koenig Press could print 400 sheets per hour. Richard Hoe, an American press maker made improvements to Koenig’s design, and in 1832 produced the Single Small Cylinder Press. In a cylinder press, a piece of paper is pressed between a flat surface and a cylinder in which a curved plate or type is attached. The cylinder then rolls over the piece of surface and produces an impression over the paper. Cylinder presses were much faster than platen and hand presses and could print between 1,000 and 4,000 impressions per hour. In 1844, Richard Hoe invented the rotary press. A rotary press prints on paper when it passes between two cylinders; one cylinder supports the paper, and the other cylinder contains the print plates or mounted type. The first rotary press could print up to 8,000 copies per hour. Larger rotary presses, containing multiple machines, made printing large newspaper runs possible.

In 1812, Friedrik Koenig invented the steam-driven printing process and dramatically sped up printing. The Koenig Press could print 400 sheets per hour. Richard Hoe, an American press maker made improvements to Koenig’s design, and in 1832 produced the Single Small Cylinder Press. In a cylinder press, a piece of paper is pressed between a flat surface and a cylinder in which a curved plate or type is attached. The cylinder then rolls over the piece of surface and produces an impression over the paper. Cylinder presses were much faster than platen and hand presses and could print between 1,000 and 4,000 impressions per hour. In 1844, Richard Hoe invented the rotary press. A rotary press prints on paper when it passes between two cylinders; one cylinder supports the paper, and the other cylinder contains the print plates or mounted type. The first rotary press could print up to 8,000 copies per hour. Larger rotary presses, containing multiple machines, made printing large newspaper runs possible.

In 1865, William Bullock invented the Bullock Press, which was the first press to be fed by continuous roll paper. The use of roll paper is important because it made it much easier for machines to be self-feeding instead of fed by hand. Once threaded into the machine, the paper was then printed simultaneously on both sides by two cylinder forms and cut by a serrated knife. The press could print up to 12,000 pages per hour, and later models could produce 30,000 pages per hour. The first roll papers were over five miles in length.

Today, roll paper is still used in many presses. Mechanical Composition Until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, all type was set and composed by hand, as in Gutenberg’s workshop.

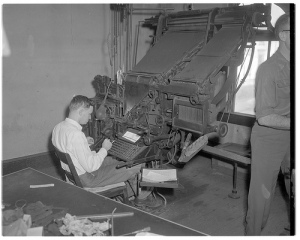

Monotype and Linotype machines changed the printing process because they used mechanical means of setting type, which was much more efficient than hand composition. In a Linotype machine, an operator would type on a keyboard similar to a typewriter, which produced a perforated band of paper. The band was then decoded by a machine that cast type from hot metal.

Monotype and Linotype machines changed the printing process because they used mechanical means of setting type, which was much more efficient than hand composition. In a Linotype machine, an operator would type on a keyboard similar to a typewriter, which produced a perforated band of paper. The band was then decoded by a machine that cast type from hot metal.

These machines cast a whole row of type at a time, so if an operator made an error it meant the whole line would have to be retyped and recast. Invented in 1889, the Monotype machine worked much like the Linotype machine. A monotype operator would similarly type out a text.

Each key stroke produced a perforated tape. The operator then tore off the tape and ran it through a separate casting machine, which produced a mould containing matrices for each character. Monotype had the advantage of being easier to correct because it was possible to remove a single letter of type, rather than having to recast a whole row of type. Monotype also produced a finer quality type, so it was frequently used in the book trade, while linotype was often used at newspaper presses because of its speed and economy.

Although some of the printing techniques we have discussed are still used, many have been revolutionized by the invention of computers. Today, a student using a personal computer is simultaneously doing the jobs of author, editor, and compositor.

Offset printing

Offset lithography is one of the most common ways of creating printed matter. A few of its common applications include: newspapers, magazines, brochures, stationery, and books. Compared to other printing methods, offset printing is best suited for economically producing large volumes of high quality prints in a manner that requires little maintenance.

Offset lithography is one of the most common ways of creating printed matter. A few of its common applications include: newspapers, magazines, brochures, stationery, and books. Compared to other printing methods, offset printing is best suited for economically producing large volumes of high quality prints in a manner that requires little maintenance.

Many modern offset presses use computer to plate systems as opposed to the older computer to film work flows, which further increases their quality.

Advantages of offset printing compared to other printing methods include:

- Consistent high image quality. Offset printing produces sharp and clean images and type more easily than, for example, letterpress printing; this is because the rubber blanket conforms to the texture of the printing surface.

- Quick and easy production of printing plates.

- Longer printing plate life than on direct litho presses because there is no direct contact between the plate and the printing surface. Properly developed plates used with optimized inks and fountain solution may achieve run lengths of more than a million impressions.

- Cost. Offset printing is the cheapest method for producing high quality prints in commercial printing quantities.

- A further advantage of offset printing is the possibility of adjusting the amount of ink on the fountain roller with screw keys. Most commonly, a metal blade controls the amount of ink transferred from the ink trough to the fountain roller. By adjusting the screws, the gap between the blade and the fountain roller is altered, leading to the amount of ink applied to the roller to be increased or decreased in certain areas. Consequently the density of the colour in the respective area of the image is modified. On older machines the screws are adjusted manually, but on modern machines the screw keys are operated electronically by the printer controlling the machine, enabling a much more precise result.[7]

Disadvantages of offset printing compared to other printing methods include:

- Slightly inferior image quality compared to rotogravure or photogravure printing.

- Propensity for anodized aluminum printing plates to become sensitive (due to chemical oxidation) and print in non-image/background areas when developed plates are not cared for properly.

- Time and cost associated with producing plates and printing press setup. As a result, very small quantity printing jobs may now use digital offset machines.

Early Printing in Malta

Nowadays, it is a fact that we are inundated by an enormous amount of printed matter that finds its way through our letter boxes. Sometimes the amount is so copious that we simply do not find the time to go through it all, despite the colorful presentation. It has not always been this way.

The history of printing does not run into thousands of years – although early civilizations did manage to find ways and means of leaving their mark through other methods.

Printing as we know it went through several phases. First came the “creative period” (circa 1300) when block printing arrived in Europe from the East, followed by a period stretching to the beginning of the 19th century when technical advances were tried, tested and consolidated until finally, by the end of the century, printing eventually turned into an industry which today uses the latest technology that has revolutionized it.

Printing in Malta goes back to the second period. It was Grand Master Lascaris who put the introduction of printing on the Order’s agenda.

Printing in Malta goes back to the second period. It was Grand Master Lascaris who put the introduction of printing on the Order’s agenda.

Jean Paul Lascaris de Castellar was elevated to the highest office in June 1636. A few months later, he attempted to set up a printing press within the Order’s domain. Despite his best efforts, nothing came easy to Lascaris – as William Zammit maintains in “Printing in Malta,” the Grand Master’s innovative idea struggled through a rough period.

By the 1630s, printing in Catholic Western Europe had spread extensively. It was not only the big cities that boasted printers and printing presses, but also much smaller towns with modest populations. Such presses for example existed in Sicily and other small towns in Southern Italy.

Due to the close proximity between Malta and Southern Italy, the Knights used the services of Italian presses for their needs. Lascaris, worried by the Knights’ growing secularization and abduction of religious vows, wanted to provide them and the reading Maltese public with printed material that would increase their religious fervor and devotion. After all, wasn’t it he who in 1656 built the “maglio” (The Mall) gardens in Floriana to keep the knights away from drinking, gambling and other vices? Lascaris was determined to have his printing press in Malta – a fact that can be attested from his well documented letters to his representatives in Rome between 1637 and 1640. Lascaris insisted that the 1631 revision of the Order’s statutes should be printed in Malta under his jurisdiction, but bearing the required approval by the Roman Curia. This could not materialize unless his bid to have a printing press on the island was accepted. The Grand Master sent the statutes for approval by the Roman Curia in 1637 – an approval that never arrived. Lascaris instructed Fra Carlo Aldobrandini, his Ambassador in Rome, to indicate to the Curia that once the all important approval was acquired he intended to bring a printer to Malta. Still, proceedings dragged on, but Lascaris remained relentless and kept urging Fra Valence (appointed ambassador after Aldobarandini’s office came to an end) to get the much awaited approval so that he could set up the printing press. Finally, after years of waiting in which nothing or very little progress was made, Lascaris had to concede defeat.

It was then that Pompeo de Fiore, a Sicilian, entered the foray. It was he who introduced the first printing press to Malta in 1642. De Fiore was not a printer himself, but was the owner of several properties; and also provided the Order with its intake of fresh bread from his bakery at Old Bakery Street in Valletta, which was bombed during WWII.

He was in close contact with influential members of the Order who were able to help him avoid paying hefty fines as well as receive compensation upon several tenements of his properties in Floriana being pulled down because they were deemed a danger to the new fortifications. His three daughters were also accepted as nuns in the Order’s convent of St. Ursula.

In June 1642, Fiore submitted a petition to the Grand Master to operate a printing press from the premises in the bakery. He also asked for a monopoly over printing in Malta for himself and his successors, and for his employees to be exempted from performing military duty. Lascaris approved all requests and signed the required license provided that all manuscripts be submitted to the grand master’s censor. In fact, it was the question of censorship that led to the printing press’ early demise. It was Fiore’s wish that the person appointed by the Grand Master to carry out the duty of censor in the Order’s name should be the Vice-Chancellor. He would have to perform his duty as censor together with the Inquisitor, whose censorship mechanism over the local press went back even before the issue of the license by Lascaris and the actual setting up of the press.

On March 8, 1642, de Fiore was summoned by the Inquisitor Giovanni Battista Gori Pannellini to take a solemn oath as required by the Council of Trent. On April 19, Cardinal Barberini on behalf of the Congregations of the Holy See informed the Inquisitor in Malta that censorship was to be his prerogative. A three-way struggle ensued between the secular, the inquisitorial and the diocesan over the control of the press, and continued over a number of years.

This meant that the Order did not encourage any further development as its Grand Master had no control over it. As a result, very few works were published and its output came to an end in 1655. Fiore’s exclusive rights to run the printing press came to an end at the same time and the family was elevated to nobility.

Another 100 years had to pass before an agreement which settled the thorny question of censorship was reached by the Holy See and the Order. In the meantime, all printing requirements were printed abroad. A State press eventually started operating in 1756 after the imprimatur issue was settled in 1746. The 1756 press has survived to this day as the Government Printing Press, being the oldest printing establishment in Malta.

Press Freedom and Early Newspapers in Malta

In 1836 Lord Glenelg, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, had issued instructions for the immediate abolition of censorship on newspapers. But the abolition of press censorship soon became a complicated issue.

In 1836 Lord Glenelg, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, had issued instructions for the immediate abolition of censorship on newspapers. But the abolition of press censorship soon became a complicated issue.

Ferdinand II, King of the Two Sicilies feared that a free press in Malta could be used by Italian liberals to bring about a revolution in his kingdom. Bishop F.S. Caruana and the Vatican were afraid to come under attack by Protestant and anticlerical publications.

Some 250 priests from a total of 750 set up a committee to show their support for a free press so long as the Church was protected. Conservative people considered political debate as dangerous for the order and stability of the colony. The Government was also afraid that military secrets could leak out to the press.

In the end, Lord Glenelg decided to grant the liberty of the press together with a law of libel to protect the interests of the Catholic Church.

The liberty of the press was proclaimed by the Governor in the Council of Government in 1839. Newspapers were published in Italian, English or Maltese. There were political, religious, cultural, commercial or satirical newspapers. Newspapers were mostly read in taverns, cafes, clubs and offices. The reading market was small and their financial resources limited. Most newspapers closed down after a few years. The British Government started issuing newspapers that defended its policies against criticism. The free press had one long-term effect – it gave the Maltese liberal leaders a new platform from which to attack the policies of the British Government and to spread their ideas and policies among the people.

The granting of press freedom by the British in March 1839 had a significant impact on the development of Maltese journalism. The newly acquired freedom of speech served as a spur not only to the hundreds of Italians exiled in Malta, who could give vent to their nationalistic aspirations which were to lead to the unification of Italy 150 years ago, but also to a consistent number of Maltese intellectuals, who were encouraged to start writing not only in Italian but also in their native tongue.

Despite the fact that many of these newspapers written in Maltese were short lived, mainly because of financial reasons but also because of the various polemics, diatribes and insults that were traded between various editors and contributors, they contributed enormously to the popularisation of the Maltese written language, which at the beginning of the 19th century was still in its infancy, without any fixed orthographic rules.

It is also thanks to the pioneering work of Maltese journalists-literati that the stabilisation of a Maltese alphabetic code was achieved. The end result of such journalistic work was the creation of the Għaqda tal-Malti alphabet in 1924.

Apart form their “linguistic-alphabetic” function, Maltese 19th century newspapers served as a medium for the spread of political ideas and ideals as well as a mouthpiece for the castigation of “bad” morals and behaviour in Maltese society, on the example of Addison and Steele’s Spectator. Religion also had a role to play in these newspapers.

In fact, some of the earliest writers and editors of the period were Anglican pastors like James Richardson and George Percy Badger who, through their newspapers in English, but also in Maltese (L’Arlecchin, Il-Kaulata), together with others like Is-serp tal-Bronz, might have made some attempt at proselytising the Maltese. Their writings obviously brought about the reaction of pro-Catholic newspapers.

These 19th century newspapers also devoted quite a lot of their space to the local theatre scene. This interest in theatre in Malta is typical of a number of other publications that did not last long, and also of the longer-lived Nafras u Colombu (November 1860 – possibly October 1862) edited and partly written by Carmelo Camilleri, comic actor and producer, and author of short farcical plays, who is an important figure in our 19th century theatre history. Camilleri, however, incurred the enmity of a number of other newspapers such as Il Furetto, Il Hatar and, most deadly of all, Bertoldu, edited by the sharp-tongued priest Giuseppe Zammit, known as Brighella, who did not refrain for passing even personal insults about.

Some Printing Presses in Malta

The Salesians Press

St.Patrick’s School opened its doors in 1904. The principal objective of the school has always been to promote boys attending the school, with a mixture of academic knowledge together with technical skills in a particular trade.

St.Patrick’s School opened its doors in 1904. The principal objective of the school has always been to promote boys attending the school, with a mixture of academic knowledge together with technical skills in a particular trade.

Boys graduating from the school would have a package that will help them throughout their lives, mainly to obtain employment and strive independently.

Printing was one of the trades taught. The school provided the practical exposure to students by means of the printing press, set the academic side of this trade. A niche area was identified and together with operating the school, the Salesians started to provide printing services to the general public. This area of business developed along the years with the printing services showing constant growth in innovative products, tailor made services.

Veritas Press

Veritas Press knows its origin to the printing press at Zebbug, Malta.

Veritas Press knows its origin to the printing press at Zebbug, Malta.

This humble beginning was the work of a number of SDC Members who back in the 1920’s came together as a small community to create what was in those days known as Tipografia Museumina. These members started off with a small printing machine, that could print a maximum area, the size of about A4.

St George Preca, the Founder of the SDC, used to visit this press whenever he needed to print any of his writings. Some of the most common writings of Fr Preca, such as A Letter on Meekness, The Great Book, and The Watch, were all printed at this press. They still had no linotypes to compose these books at this stage and therefore had to use movable types to prepare the text.

In the 1950’s, these Members moved the printing press from Zebbug to the SDC Zabbar Centre and some years later, the press moved to a large newly-built premises, more commonly known as Istitut Sagra Familja.

The management of press embarked on a new project, that of printing newspapers. This brought about a number of changes, linotypes were introduced, and a big Duplex Rotary printing machine was bought. The name of the Press was changed firs to Stamperija Sagra Familja (Holy Family Press), and then to Veritas Press.

The management of press embarked on a new project, that of printing newspapers. This brought about a number of changes, linotypes were introduced, and a big Duplex Rotary printing machine was bought. The name of the Press was changed firs to Stamperija Sagra Familja (Holy Family Press), and then to Veritas Press.

For a number of years, a daily newspaper called Il-Haddiem (The Worker) was printed at Veritas, together with a good number of books and magazines, amongst them Kliem il-Hajja (The Word of Life).

It was in 1979 that the core group of these SDC Members felt that they were not in a position to continue to shoulder the responsibility of running the press, thus in January 1980 the SDC Administration created a body to administer the Press.

In October of the same year, the general direction of Veritas was entrusted to Mr John Formosa sdc. A second major restructuring programme for Veritas Press ensued. This included the buying of a modern two-colour offset printing machine, as well as other ancillary machines to help in the finishing processes such as: a folder, gluer and a thread-stitcher. At this time, all the pre-press work was still out-sourced to other presses.

This came to an end in the mid1980’s, when the press developed its own type-setting department as well as dark-room, thus enabling it to do all the pre-press in house. As in all other fields, technology brought about great changes in the printing industry, therefore Veritas had to embark once more on buying and introducing bigger two-colour printing machines as well as image-setters that could produce its own films for mono or four colour separations. Today, apart from a number of established clients, mainly Schools, Local Councils, Factories, Businesses and individuals, Veritas Press, is responsible for all the printing needs of the Society of Christian Doctrine, M.U.S.E.U.M.

This came to an end in the mid1980’s, when the press developed its own type-setting department as well as dark-room, thus enabling it to do all the pre-press in house. As in all other fields, technology brought about great changes in the printing industry, therefore Veritas had to embark once more on buying and introducing bigger two-colour printing machines as well as image-setters that could produce its own films for mono or four colour separations. Today, apart from a number of established clients, mainly Schools, Local Councils, Factories, Businesses and individuals, Veritas Press, is responsible for all the printing needs of the Society of Christian Doctrine, M.U.S.E.U.M.

Veritas Press has weathered a number of difficulties especially in today’s modern competitive environment. Yet when considering its size and compared to others much bigger printing presses, it is still very competitive, and equipped well enough to keep old clients and to attract new ones too.

Government Press

One of the most popular employees at the government printing press when this was located at the Grandmasters Palace in Valletta and later at St James Cavalier, also in the capital city, was Guzeppi Farrugia, endearingly known as Zeppi tac-Comb.

One of the most popular employees at the government printing press when this was located at the Grandmasters Palace in Valletta and later at St James Cavalier, also in the capital city, was Guzeppi Farrugia, endearingly known as Zeppi tac-Comb.

His job was to ferry the “slugs” up to the roof of the palace. Each line of copy was made of lead and after use these slugs were melted to be used again by linotypists.

On the palace roof, Mr Farrugia fired a forge in which he melted the slugs and poured the molten lead in moulds shaped like ingots for the lead to be re-used. A linotype (a trade name) was a typesetting machine operated by a keyboard and cast an entire line of text as one solid slug of lead. The lead was melted in a sizeable pot forming part of the linotype machine. The government printing press changed over from letterpress and the use of lead to offset in the early 1990s. “The government printing press was the last press on the island to hang on to linotype,” Mr Sammut recalled. When he joined the civil service as an apprentice, Mr Sammut received a salary of £13 a month. In 1971, after applications were issued for the post of printer, Mr Sammut sat for the exam and placed first.

At that time, the staff complement at the press was about 110; today it amounts to 60. “We were responsible for big print jobs such as the national lottery tickets, the results of that lottery and the applications for tickets because tickets were sold world-wide. “At that time there were many agents selling national lottery tickets to punters in other countries. “We used wooden fonts to print posters. “In the case of the weekly lotto, we used to print 1.25 million tickets a week in quadruplicate.

This job was so extensive that two employees from the now defunct Lotto Department spent almost all of their time at the press.”

In 1975, the press migrated to St James Cavalier and spent 20 years there. It is now at the Marsa industrial estate. “The Cavalier was not an ideal place for a press because the machines was laid out on several floors. There was only one lift which when out of order meant hardship for the workers because they had to carry each page containing so many slugs of lead. “This was particularly tiring especially when we were preparing voluminous works such as the electoral register. “The same applied to the printing of the national budget which meant printed copies of the English and Maltese versions of the speech by the Minister of Finance, the estimates and the economic survey.” When printing the budget, the telephones at the press were disconnected to avoid leaks to the media and to importers, especially details about the price of food and alcoholic beverages that could have changed. “We were ferried home by charabanc, at times getting home two hours after one left the press because the driver had so many stops to offload passengers along the way! “It was not unusual for a policeman to call for you at home to get back to the press in order to tackle an urgent job.”

In 1975, the press migrated to St James Cavalier and spent 20 years there. It is now at the Marsa industrial estate. “The Cavalier was not an ideal place for a press because the machines was laid out on several floors. There was only one lift which when out of order meant hardship for the workers because they had to carry each page containing so many slugs of lead. “This was particularly tiring especially when we were preparing voluminous works such as the electoral register. “The same applied to the printing of the national budget which meant printed copies of the English and Maltese versions of the speech by the Minister of Finance, the estimates and the economic survey.” When printing the budget, the telephones at the press were disconnected to avoid leaks to the media and to importers, especially details about the price of food and alcoholic beverages that could have changed. “We were ferried home by charabanc, at times getting home two hours after one left the press because the driver had so many stops to offload passengers along the way! “It was not unusual for a policeman to call for you at home to get back to the press in order to tackle an urgent job.”

The printing press has a formidable history going back to June 28, 1756 when the Order of the Knights of St John set it up. The first copy of the Government Gazette was printed in 1813 and, although Malta was then under British rule, the gazette was printed in Italian, the language of the courts and of the government for so many centuries. “At that time, the gazette was completely hand set letter by letter. Today’s gazette has more or less kept to the original layout.

Although computers have taken over many of the manual tasks, there will always be the need for hard copies. “It is true, though, that lotto tickets, the Gozo Channel ferry tickets, bus tickets and museum tickets are now printed on the spot by specialised machines.

“Also, before the advent of computers, the Government Gazette had a print run of 3,000 copies but the demand has now gone down to 1,000 copies, most probably because the information is available online. “Alas, computers have taken away the joy and pride of the master printers of the pre-digital world. “One of toughest tests for a printer in those days was to print a court of arms of Malta in a four colour letterpress process and then add gold and silver. If you were capable of printing such a crest, you were capable of printing anything.”

Reminiscing about the good old days, Mr Sammut explained that each apprentice used to be assigned to one of the master printers who was paid an extra shilling (the equivalent of today’s 12c) daily for having an understudy.

“Also because of the amount of lead in the air emanating from the linotype machines, printers were given half a bottle of milk everyday and they had their blood tested for lead content every three months. “There were times when the three months turned into six. At the time the level of awareness about health hazards at work was nothing like it is today,” Mr Sammut recalled.

Progress Press

Progress Press was actually set up as a political printing press by Lord Strickland. He bought his first printing machines in 1921 and the press was formally set up in 1922.

Progress Press was actually set up as a political printing press by Lord Strickland. He bought his first printing machines in 1921 and the press was formally set up in 1922.

Strickland needed his newspapers to fend off the political rivals. By 1927 he was Head of the Ministry (Prime Minister) having formed an alliance (the compact) with the Labour Party.

The press took its name from Il-Progress, a weekly evening newspaper which Strickland started publishing some months before buying his first printing machines.

The first two machines were bought in July 1921 and Progress Press was set up in what is now Republic Street next to the Church of Sta Barbara. The name ‘Progress’ captured the mood of the country at the time, the dawn of self-government.

The first building to host Progress Press consisted of a large entrance, an office, three rooms where the printing machines were installed, a printers’ office, a store room and a number of other rooms. The press was valued at £3,340.

The first milestone for the new press was reached on February 3, 1922 when Strickland launched an English supplement to Il-Progress – The Times of Malta – a title which 13 years later was to become a daily national newspaper. In 1924 a bilingual newspaper – The Times of Malta u ‘l Progress, was launched.

New ground was broken with Ix-Xemx (The Sun) an afternoon daily which was launched on September 22, 1928. This was the first ever Maltese language daily, reaching a circulation of over 4,000, high for that time.

Its purpose, the newspaper said, was to fight ‘the poisonous vipers’ that were crushing Malta’s name under their feet.

Ix-Xemx was banned by the Church on May 6, 1930 and Strickland, on the following day, turned Il-Progress into a daily. When that too fell foul of the Church, Progress Press launched Id-Dehen as another daily, which was later similarly banned. Il Berka (Il-Berqa) then followed.

In time, Progress transformed itself from a political to a commercial enterprise, with the newspapers becoming national rather than political.

In 1931 the press moved to 341 St Paul Street, taking over a building built in 1910 and used as a cigarette-making factory by Constantine Colombos. During the time of the Knights, the same site was occupied by the Palace of the Fountains, of which nothing survives.

In 1931 the press moved to 341 St Paul Street, taking over a building built in 1910 and used as a cigarette-making factory by Constantine Colombos. During the time of the Knights, the same site was occupied by the Palace of the Fountains, of which nothing survives.

Strickland House, as it has been called since, was bought out of a loan of €5,564 provided by Lady Strickland. By 1948 the value of the building was estimated at £22,000.

Strickland House was hit twice by bombs in the second world war but the production of the newspapers was never halted. Strickland, however, had taken the precaution of dispersing his newsprint warehouses. He also set up some printing machines at his residence, Villa Bologna – just in case.

In the decades following the war, Progress Press developed as a major commercial printing press while continuing to print the newspapers.

A socialist mob badly damaged the premises and some of the machines on October 15, 1979 during a political protest, and the front part of the building had to be rebuilt.

A socialist mob badly damaged the premises and some of the machines on October 15, 1979 during a political protest, and the front part of the building had to be rebuilt.

But the biggest problem to face the press over the years was the space it needed for its machines. Walls were demolished and the configuration of machines was altered in a manner which amazed foreign engineers, but the company eventually had to bow to the inevitable and decided to move out of Valletta.

The contract for the land in Mrieħel was signed in June 2009. The contract of works followed a month later and the project began in September 2009. Exactly a year later, Progress Press began printing The Times at the new premises.

Apart from ancillary machines, 15 major units of equipment were transferred, including a computer-to-plate machine, three printing machines, four folders, three guillotines, a stitcher, and a book binder.

The transfer created logistical challenges, both in terms of equipment haulage as well as production planning. Layout and space restrictions in Valletta implied that structural changes had to be made to the building and walls were torn open to create passageways for the equipment’s exit. Additionally, specialised scaffolding was required at the rear of the building to facilitate safe lowering of the machines to street level onto the hauling trucks. To create minimum disruptions possible to production, the transfer was planned and executed in phases. This enabled part-production to proceed in Valletta while initial equipment was dis-assembled, hauled and re-assembled at Mrieħel.

The transfer created logistical challenges, both in terms of equipment haulage as well as production planning. Layout and space restrictions in Valletta implied that structural changes had to be made to the building and walls were torn open to create passageways for the equipment’s exit. Additionally, specialised scaffolding was required at the rear of the building to facilitate safe lowering of the machines to street level onto the hauling trucks. To create minimum disruptions possible to production, the transfer was planned and executed in phases. This enabled part-production to proceed in Valletta while initial equipment was dis-assembled, hauled and re-assembled at Mrieħel.

When the first transferred modules were operational in Mrieħel, a second module at Valletta was dis-assembled and transferred. This proceeded successively for a three-month period until all equipment and production was operating from Mrieħel towards end of March 2010. All equipment underwent a specialised cleaning and maintenance programme before reassembly.

Web printing on coated paper is a production line which enables Progress Press to enter the high volume market, particularly that of door-to-door material. Progress Press’s capability of reaching volumes ranging between 20,000 and 300,000 “with ease” enables the company to bid for international business on high volumes in a competitive market.

MALTESE NEWSPAPERS

A key date in the history of journalism in Malta is 1839. The British introduced for the first time the liberty of the press. Liberty of the press was achieved through the work of Giorgio Mitrovich. The change of government in Britian also helped to achieve it. That particular decade in Europe was characterised by the revolutionary spirit which had its genesis in France in 1789.

The last two centuries saw several papers each of them advocating the cause of its publisher. Some were anti British. Some favoured the Italians. Some wanted a stronger papacy. A few others tried to appeal to the working class.

THE PROGRESS PRESS

The first newspaper to be published by this press was IL-BERQA. It was a daily paper but took a vacation on Sunday. The first issue was published on 28 May 1930. The last issue was on 30 November 1968. Three years later THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA was published. For a period of time Mabel Strickland was its editor.

THE TIMES OF MALTA was first published in 1935. Today THE TIMES is Malta’s only daily. What dominated these newspapers was culture. Front pages were usually dominated by foreign news. The papers favoured British presence on the islands and were considered as organs of the Strickland party.

THE UNION PRESS

The union print is a property of the GWU – Malta’s largest trade union. The union was founded by Reggie Miller.

As time passed the Union print papers carried across the message of the MLP headed at time by Duminku Mintoff. Miller himself was the editor of THE TORCH which remained bilingual up to 1959.

Between the years 1958/67, the editor of IT-TORCA was John Attard Kingswell. November 1962 witnessed the birth of L-ORIZZONT a daily still existing today with the subtitle “indipendenti ta’kuljum”. Another paper to be published by this press in the fifties was IS-SEBH edited by Joe Micallef Stafrace lawyer and former MLP deputy. It also published IL-HELSIEN which was registered twice in its history. Firstly it was issued as a daily between 1958 and 1967 and re-issued again between 1980-88. It was replaced later on by KULLHADD edited by Felix Agius and Evarist Bartolo.

THE LUX PRESS

A very active press in postwar Malta was LUX PRESS run by Anthony Micallef, known as “is-sur Tonin”. It published the organs of the following parties:

MALTA TAGHNA for the Partit Demokratiku Nazzjonalista led by H. Ganado, and for the Nationalist Party IL-POPLU.

The former party was an offshoot of the latter. Dr. Eddie Fenech Adami was the editor of IL-POPLU. Il-POPLU was published weekly. Both newspapers had 4 pages and were priced at 2d.

THE CHURCH PRESS

The 20th Century witnessed a number of church papers. The first Catholic paper was LEHEN IS-SEWWA. It was published by Azzjoni Kattolika. Another paper was IL-HAJJA which boasted of repecting the intelligence of its readers. It was later replaced by the weekly IL-GENS.

THE NATIONALIST PRESS

The PN started to own a press of its own in 1970. The first paper to publish was IN-NAZZJON TAGHNA. Before the elections of 1987 Eddie Fenech Adami was the editor of this daily. IL-MUMENT was started a year later. Its first editor was Michael Refalo.

OTHERS

1989 saw the publication of a forthnight paper published by a newly born party founded by Toni Abela and Wenzu Mintoff after their expulsion from the MLP. The party was called Alternattiva Demokratika and their paper L-ALTERNATTIVA.

Three years later another weekly in English was launched – THE MALTA INDEPENDENT owned by a group of businessmen. The Standard Publications also publish THE MALTA BUSINESS WEEKLY.

THE PEOPLE and THE PEOPLE ON SUNDAY had a very short history, spanning over just a couple of years between 1996 and 1998. Their tabloid style did not capture much public support and had to cease publication. The staff of the newspapers were employed by Network Publications who continued to publish THE BUSINESS TIMES every week. The same publishing house started the MALTA TODAY in 1999.

Do you know where fliers for shows (ex. Drag shows in Strada Stretta) would be printed, please?