Referenda Results

Introduction |

Only seven referenda have ever been held in Malta; one of them was a purely local one in Gozo.

Professor John C. Lane of Buffalo University, New York, says, of referenda in Malta and Gozo, that “it is remarkable that no referendum (except the 1870 referendum) received the approval of a majority of all the registered voters, because often substantial numbers of voters did not cast a vote“. Lane is an expert on electoral processes and voting systems and has compiled a most informative website on Maltese elections and referenda. He was in Malta in 1996 to see at first hand how our proportional representation system worked.

It is important to note that in any case he is on the side of those who subscribe to the calculation of referendum results on the basis of ‘valid votes’, that is the votes cast by actual voters. After all, this has always been the position recognised by the Maltese legal system and was not changed when the Referenda Act was discussed by Parliament and amended in October, 2002.

Referring to the way referendum figures are reproduced by various authors, Lane has to register that ‘the referenda results involve a problem in respect to the total number of voters’. In particular he refers to Edith Dobie (Malta’s Road to Independence, 1967), Joseph Pirotta (Fortress Colony: The Final Act, Vol. II, 1991) and Edgar Mizzi (Malta in the Making, 1995) as reporting ‘the figure of all registered voters which would include, for instance, voters who were deceased between the time the electoral register was compiled and the polling day’.

On the other hand, he says, Remig Sacco (L-Elezzjonijiet Generali, 1986), Michael Schiavone (L-Elezzjonijiet f’Malta, 1992) and Henry Frendo (The Origins of Maltese Statehood, 1999) go for “the number of voters who were issued their voting documents”. These are the ‘eligible voters’, and it is on these that Lane bases his computation of the official referenda results, although he gives all the available figures for invalid votes and for votes not withdrawn from the Electoral Office.

Obviously, the problem lies with the calls for boycotts made in the case of three nationwide referenda.

The first referendum to be held in Malta was that of 1870 when the question put to the electorate was: ‘Are ecclesiastics to be eligible to the Council of Government?’. At the time only a small section of the population (one could call them the landed gentry) had the right to vote.

In 1956 Maltese and Gozitans were called to cast their vote in a referendum on the Labour government’s ‘Integration with Britain’ proposal. Voting was held on February 11 and 12, 1956. It is pertinent to note that voters were allowed to be accompanied into the polling booth by a ‘trusted friend’ who could help them cast their vote. From a legal point of view the Yes vote carried the day, but the total of those voting against, those abstaining or invalidating their vote, the deceased, and the ‘non-voters’ exceeded the yes vote by almost 10 per cent.

In the Constitution referendum of 1964 the electorate was called to answer the question: “Do you approve of the constitution proposed by the Government of Malta, endorsed by the Legislative Assembly, and published in the Malta Gazette?”

The Nationalist government was obviously for a Yes vote, while the Labour Party told its members to vote No. The Christian Workers Party and the Progressive Constitutional Party asked the electorate to abstain from voting while the Democratic Nationalist Party opted for invalidation of the vote or a blank vote.

Voting took place on May 2, 3 and 4, 1964. Once again, the Yes vote carried the day. But once again one has to go to historians Frendo and Pirotta to understand why the British government, influenced by decisions at a time when military logistics were going through great changes and Malta’s strategic position was gradually diminishing, opted to honour the official Yes result.

Under a Labour government, a referendum was held in Gozo in 1973 on the abolition of the Gozo Civic Council; only voters registered in Gozo could cast their vote.

The question, a loaded one if ever there was one, ran as follows: “Do you want Gozo to remain different from Malta, that is, not only having its own representatives in Parliament, chosen from Gozo, but also representatives in the Gozo Civic Council which, amongst other powers, has that of imposing special taxes on the Gozitans to be spent according to the wishes of the people of Gozo?”

The majority of the few who voted were in favour, but the Gozo Civic Council instructed the Gozitans to boycott the referendum precisely because of the loaded nature of the question.

Voting took place on November 11, 1973. Mr Mintoff abolished the council, as seems to have been his intention all along.

The European Union referendum was held on March 8, 2003 answering the question: “Do you agree that Malta becomes a member of the European Union in the enlargement that will take place on May 1, 2004?”. A narrow majority voted in favour of joining but the opposition Labour Party rejected the results. Supporters of the Nationalist party celebrated the result of the referendum but the Labour leader Alfred Sant did not concede defeat and said the issue would be settled at the upcoming general election. He argued that only 48% of registered voters had voted yes and that therefore a majority had opposed membership by voting no, abstaining or spoiling their ballot. The day after the referendum the Prime Minister called the election for the 12 April as expected, though it was not required until January 2004.

The main issue in the 2003 election was EU membership and the Nationalist party’s victory enabled Malta to join on the 1 May 2004.

A private member’s bill was tabled in the House of Representatives by Jeffrey Pullicino-Orlando, a Nationalist Member of Parliament. The text of the bill, which had been changed twice, did not provide for the holding of a referendum. This was eventually provided for through a separate Parliamentary resolution under the Referenda Act authorising a facultative, non-binding referendum to be held.

The Catholic Church in Malta encouraged a “no” vote through a pastoral letter issued on the Sunday before the referendum day. Complaints were made that religious pressure was being brought to bear upon voters.

The divorce referendum was held in Malta on 28 May 2011 to consult the electorate on the introduction of divorce, and resulted in a majority of the voters approving legalisation of divorce. At that time, Malta was one of only three countries in the world, along with the Philippines and the Vatican City, in which divorce was not permitted. As a consequence of the referendum outcome, a law allowing divorce under certain conditions was enacted in the same year. Parliament approved the law on 25 July. The law came into effect on 1 October 2011.

The seventh Referendum, on Spring Hunting, was held on Saturday 11 April 2015. This was the first referendum to be held after a petition brought by the public in terms of the law. More than 50% of electors have to turn up and vote in a referendum for the outcome to hold. Some 75% of the eligible voters cast their preference at this referendum, which was more than the 71% cast in the referendum on divorce In 2011. The “yes” camp won the spring hunting referendum which meant that the hunting practice in spring continued in Malta.

1956 Integration Referendum11-12 February 1956

Voting was held on February 11 and 12, 1956. It is pertinent to note that voters were allowed to be accompanied into the polling booth by a ‘trusted friend’ who could help them cast their vote. From a legal point of view the Yes vote carried the day, but the total of those voting against, those abstaining or invalidating their vote, the deceased, and the ‘non-voters’ exceeded the yes vote by almost 10 per cent. A good look at history, especially as recorded by Henry Frendo and Joseph Pirotta, would show that the British government’s decision not to abide by the decision taken by the ‘valid voters’ had little to do with the actual result. In simple terms, the British cabinet, influenced mostly by the Admiralty, had had second thoughts. The underlying principle of the proposals for closer association with Great Britain was complete equality of status between the two peoples . The Opposition Party boycotted the referendum. Out of a total electorate of 152,823, the number of people who cast their vote was 90,343 or 59.1 per cent “Yes” votes were 67,607 and “No” votes 20,177; the number of invalid votes amounted to 2,559. The Question “Do you approve of the proposals as set out in the Malta Government Gazette of the 10th January, 1956?”

The Result:

* of these 3,287 did not collect voting document

Aftermath 77.02% of voters were in favour of the proposal, but owing to a boycott by the Nationalist Party, only 59.1% of the electorate voted, thereby rendering the result inconclusive. There were also concerns expressed by British MPs that the representation of Malta at Westminster would set a precedent for other colonies, and influence the outcome of general elections. In addition, the decreasing strategic importance of Malta to the Royal Navy meant that the British government was increasingly reluctant to maintain the naval dockyards. Following a decision by the Admiralty to dismiss 40 workers at the dockyard, Dom Mintoff declared that “representatives of the Maltese people in Parliament declare that they are no longer bound by agreements and obligations toward the British government…” (the 1958 Caravaggio incident). In response, the Colonial Secretary sent a cable to Mintoff, stating that he had “recklessly hazarded” the whole integration plan. Dom Mintoff resigned as Prime Minister, and Giorgio Borg Olivier declined forming an alternative government. This led to the Islands being placed under direct colonial administration from London, with the MLP abandoning support for integration and now advocating independence. In 1959, an Interim Constitution provided for an Executive Council under British rule. While France had implemented a similar policy in its colonies, some of which became overseas departments, the status offered to Malta from Britain constituted a unique exception. Malta was the only British colony where integration with the UK was seriously considered, and subsequent British governments have ruled out integration for remaining overseas territories, such as Gibraltar. In 1961, the Blood Commission provided for a new constitution allowing for a measure of self-government and recognizing the “State” of Malta. Giorgio Borg Olivier became Prime Minister the following year, when the Stolper report was delivered. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1964 Constitution Referendum2, 3 & 4 May, 1964 |

In the Constitution referendum of 1964 the electorate was called to answer the question: “Do you approve of the constitution proposed by the Government of Malta, endorsed by the Legislative Assembly, and published in the Malta Gazette?“

In the Constitution referendum of 1964 the electorate was called to answer the question: “Do you approve of the constitution proposed by the Government of Malta, endorsed by the Legislative Assembly, and published in the Malta Gazette?“

The Nationalist Government was obviously for a Yes vote, while the Labour Party told its members to vote No. The Christian Workers Party and the Progressive Constitutional Party asked the electorate to abstain from voting while the Democratic Nationalist Party opted for invalidation of the vote or a blank vote.

Voting took place on May 2, 3 and 4, 1964. Once again, the Yes vote carried the day. But once again one has to go to historians Frendo and Pirotta to understand why the British government, influenced by decisions at a time when military logistics were going through great changes and Malta’s strategic position was gradually diminishing, opted to honour the official Yes result.

Out of the 156,886 people entitled to vote, 129,649 cast their votes or 83.4 per cent. The number of “Yes” votes was 65,714 and the number of “No” votes was 54,919 while 9,016 votes were declared invalid.

The Question:

“Do you approve of the constitution proposed by the Government of Malta, endorsed by the Legislative Assembly, and published in the Malta Gazette?“

The Result:

| The Referendum of 1964 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice | Votes | % Registered Voters | % Votes Cast | %Valid Votes |

| In Favour | 65,714 | 40.38 | 50.69 | 54.47 |

| Against | 54,919 | 33.75 | 42.36 | 45.53 |

| Registered Voters | 162,743 | 100 | ||

| Non Voting* | 33,094 | 20.34 | ||

| Votes Cast | 129,649 | 79.66 | 100 | |

| Invalid Votes | 9,016 | 5.54 | 6.95 | |

| Valid Votes | 120,633 | 74.12 | 93.05 | 100 |

* of these 5,899 did not collect their voting document

Aftermath

It was effectively a referendum on independence, as the new constitution made the country an independent nation on 21 September 1964.

1973 Gozo Referendum.11 November, 1973 (note that only voters in Gozo could cast votes)

The question, a loaded one if ever there was one, ran as follows: “Do you want Gozo to remain different from Malta, that is, not only having its own representatives in Parliament, chosen from Gozo, but also representatives in the Gozo Civic Council which, amongst other powers, has that of imposing special taxes on the Gozitans to be spent according to the wishes of the people of Gozo?” The majority of the few who voted were in favour, but the Gozo Civic Council instructed the Gozitans to boycott the referendum precisely because of the loaded nature of the question. Voting took place on November 11, 1973. Out of 15, 621 people entitled to vote, 195 cast their votes or 1.25%. The number of “Yes” votes was 137 and the number of “No” votes 41, while 17 votes were declared invalid The Question: “Do you want Gozo to remain different from Malta, that is, not only having its own representatives in Parliament, chosen from Gozo, but also representatives in the Gozo Civic Council which, amongst other powers, has that of imposing special taxes on the Gozitans to be spent according to the wishes of the people of Gozo?” The Result:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

2003 European Union Referendum8 March, 2003 |

A referendum on joining the European Union was held in Malta on 8 March 2003. A narrow majority voted in favour of joining but the opposition Labour Party rejected the results. The victory of the Nationalist Party in the 2003 general election confirmed the result of the referendum and Malta joined the EU on 1 May 2004.

A referendum on joining the European Union was held in Malta on 8 March 2003. A narrow majority voted in favour of joining but the opposition Labour Party rejected the results. The victory of the Nationalist Party in the 2003 general election confirmed the result of the referendum and Malta joined the EU on 1 May 2004.

The Maltese referendum saw the highest turnout, and the lowest support for joining, of any of the nine countries that held referendums on joining the EU in 2003.

The European Union referendum was held on March 8, 2003 answering the question: “Do you agree that Malta becomes a member of the European Union in the enlargement that will take place on May 1, 2004?”

Out of 297,881 registered voters, 270,650 votes were cast or 90.86%. 3,911 votes were invalid, with 143,094 in favour and 123,628 against.

The Question:

“Do you agree that Malta becomes a member of the European Union in the enlargement that will take place on 1 May 2004?”

The Result:

| The Referendum of 2003 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice | Votes | % Registered Voters | % Votes Cast | %Valid Votes |

| In Favour | 143,094 | 48.04 | 52.87 | 53.65 |

| Against | 123,628 | 41.50 | 45.68 | 46.35 |

| Registered Voters | 297,881 | 100 | ||

| Non Voting | 27,231 | 9.14 | ||

| Votes Cast | 270,650 | 90.86 | 100 | |

| Invalid Votes | 3,911 | 1.31 | 1.45 | |

| Valid Votes | 266,722 | 89.54 | 98.55 | 100 |

Aftermath

Supporters of the Nationalist party celebrated the result of the referendum but the Labour leader Alfred Sant did not concede defeat and said the issue would be settled at the upcoming general election. He argued that only 48% of registered voters had voted yes and that therefore a majority had opposed membership by voting no, abstaining or spoiling their ballot. The day after the referendum the Prime Minister called the election for the 12 April as expected, though it was not required until January 2004.

The main issue in the 2003 election was EU membership and the Nationalist party’s victory enabled Malta to join on the 1 May 2004.

2011 Divorce Referendum.28 May 2011

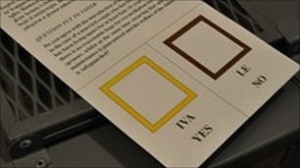

The Catholic Church in Malta encouraged a “no” vote through a pastoral letter issued on the Sunday before the referendum day. Complaints were made that religious pressure was being brought to bear upon voters. The divorce referendum was held in Malta on 28 May 2011 to consult the electorate on the introduction of divorce, and resulted in a majority of the voters approving legalisation of divorce. At that time, Malta was one of only three countries in the world, along with the Philippines and the Vatican City, in which divorce was not permitted. As a consequence of the referendum outcome, a law allowing divorce under certain conditions was enacted in the same year. Question Ballot papers had both English and Maltese questions printed on them. The English version of the question put to voters was as follows:

Taqbel mal-introduzzjoni tal-għażla tad-divorzju f’każ ta’ koppja miżżewġa li tkun ilha separata jew tkun ilha ma tgħix flimkien għal mill-anqas erba’ (4) snin, u meta ma jkun hemm l-ebda tama raġjonevoli ta’ rikonċiljazzjoni bejn il-miżżewġin, filwaqt li jkun garantit manteniment adegwat u jkunu mħarsa t-tfal?

The Result:

Although for the referendum the whole country was considered as a single constituency, taking into account electoral districts, only three out of thirteen voted “no” to the referendum question |

|||||||||||||||||||||

2015 Hunting Referendum.

11 April 2015

The process leading to the first referendum organised as a result of a nationwide petition was kicked off in the summer of 2013, when green party Alternattiva Demokratika and a group of environmental NGOs – BirdLife Malta, the Coalition for Animal Rights, Din l-Art Ħelwa, Flimkien għal Ambjent Aħjar, Friends of the Earth Malta, Gaia Foundation, Greenhouse Malta, International Animal Rescue Malta, Moviment Graffiti, Nature Trust and the Ramblers Association of Malta – joined forces to form the Coalition Against Spring Hunting (CASH).

The Referenda Act allows for the holding of an abrogative referendum if it is backed by at least 10% of the electorate, a figure which in 2014 translated to some 34,000 people. But no attempt to organise one has been successful till 2014: a petition AD had organized in 2005 to reform rent laws had been unsuccessful.

The main hunters’ association FKNK and the St Hubert Hunters filed a Constitutional case listing their objections to the referendum over 22 pages. On 9 January 2015 the Constitutional Court made a decision to allow a referendum on Spring hunting to take place. The Prime Minister, at a press conference, said that the referendum will be held on Saturday 11 April 2015.

This is the first referendum to be held after a petition brought by the public in terms of the law. More than 50% of electors have to turn up and vote in a referendum for the outcome to hold.

Petition

By November 2013 over 44,000 people signed the petition calling for a referendum to end spring hunting on Malta. The petition called for an abrogative referendum to remove the legislation that allows spring hunting. At least 10 per cent of the Maltese electorate (that can vote in a general election) must sign the petition with details as printed on their ID card for the referendum to be allowable – around 34,500 people.

Referenda Act: Declaration for the holding of a Referendum. We the undersigned persons, being registered as voters for the election of members of the House of Representatives, demand that the question whether the following provision of law, that is to say Framework for Allowing a Derogation Opening a Spring Hunting Season for Turtledove and Quail Regulations (Subsidiary Legislation 504.94 – Legal Notice 221 of 2010) should not continue in force, shall be put to those entitled to vote in a referendum under Part V of the Referendum Act.

Att dwar ir-Referendi : Dikjarazzjoni għaż-Żamma ta’ Referendum. Aħna hawn taħt iffirmati li aħna persuni rreġstrati bħala eletturi għall-elezzjoni ta’ membri fil-Kamra tad-Deputati qegħdin nitolbu li l-mistoqsija dwar jekk dawn id-disposizzjonijiet tal-liġi li ġejjin, jiġifieri Regolamenti dwar qafas biex tiġi permessa Deroga li tiftaħ l-istaġun għall-kaċċa tal-gamiem u summien fir-Rebbiegħa (Leġislazzjoni Sussidjarja 504.94 – Avviż Legali 221 tal-2010) għandhomx jibqgħu jseħħu, għandha ssir lil dawk il-persuni bil-jedd li jivvutaw f’referendum skont it-Taqsima V tal-Att dwar ir-Referendi.

On 16 December 2013 the FKNK launched its own campaign, to collect signatures for a petition to amend the Referendum Act so as to “protect the rights, interests, and privileges for all minorities.” The Petition was signed by over 104,000.

In October 2014 FKNK told the Constitutional Court that a referendum to abolish spring hunting cannot be held because it breaches Malta’s EU Treaty obligations. The hunting federation, FKNK, argued that the referendum sought to abolish a legal notice that implemented provisions of the Birds Directive, which Malta was obliged to transpose as a result of EU accession. An abrogative referendum cannot be held to remove certain laws such as those that emanate from treaties the country has ratified. “Removing the legal notice will mean that the balance between bird protection and recreational needs mandated by the Birds Directive and confirmed by the European Court of Justice is lost,” the federation argued.

The objection filed by lawyer Kathleen Grima was one of others listed in a 22-page submission made to the Constitutional Court asking it to reject the petition and stop the abrogative referendum. According to the Referenda Act it is the Constitutional Court that will decide whether the referendum can be held after hearing submissions for and against. Objections can only be made on very limited grounds concerning a point of law.

The Coalition to Abolish Spring Hunting collected more than 44,000 signatures calling for the holding of an abrogative referendum to strike out the 2010 legal notice that makes spring hunting possible. The hunting federation noted that the Referenda Act prevented the holding of a referendum to abolish any legislation of a fiscal nature. While acknowledging that the spring hunting legal notice was not “strictly” fiscal legislation, FKNK said that it had elements of a fiscal nature when it referred to the acquisition of a hunting licence. Hunters insisted that the coalition’s drive to remove the whole legal notice also went against the spirit of the Referenda Act. The federation argued that an abrogative referendum could be held to abolish “a part or parts” of a law but not to remove a law in its entirety. The coalition’s proposal went against good public order, the federation added.

The legal challenge noted that according to law, the proponents of a referendum had to be more than five and not more than 10, identifiable and the first to sign the petition. Hunters insisted the proponents could not be identified in the petition and so it was not possible to verify whether the legal condition was satisfied.

On 9 January 2015 the Constitutional Court, made up of Chief Justice Silvio Camilleri, Mr Justice Giannino Caruana Demajo and Mr Justice Noel Cuschieri found no grounds for the referendum not to be held.

Campaign

Shout – the ‘No’ to spring hunting referendum campaign was launched on Saturday 17 January 2015 by the Campaign for the Abolition of Spring Hunting.

The campaign, entitled Sping Hunting Out (Shout),was based on providing information through a number of spokespersons who included Moira Delia, Renzo Spiteri, Joe Mangion, Frank Zammit, Carina Camilleri, Seb Tanti Burlo, Iggy Fenech, Nick Morales and Saviour Balzan.

Question

Ballot papers had both English and Maltese questions printed on them.

The English version of the question put to voters was as follows:

“Do you agree that the provisions of the Framework for allowing a Derogation opening a Spring Hunting season for Turtle Dove and Quail Regulations (subsidiary legislation 504.94) should continue in force?”

The Maltese version was:

“Taqbel illi d-dispożizzjoni tar-‘Regolamenti dwar Qafas biex tigi permessa Deroga li tiftaħ l-Istaġun għall-Kaċċa tal-Gamiem u tas-Summien fir-Rebbiegħa’ (Leġislazzjoni Sussidjarja 504,94) għandhom jibqgħu fis-seħħ?”

The Result:

The Result:

The Referendum of 2015Choice Votes Percentage In Favour

126,434 50.44% Against

124,214 49.56% Invalid or blank votes 2,509 Total votes 253,157 100.00% Voter turnout 75%

Aftermath

The “yes” camp won the spring hunting referendum which meant that the hunting practice in spring continued in Malta.