Shared by Joe Arevalo

Definition

Maltese is part of the family Hamito-Semitic also called Afro-Asiatic languages. Within this family, it is part of the group of Semitic languages. Current Maltese, who is the heir of Arabic Maltese is historically part of the Sicilian-Arabic, with siqili (Arabic Sicilian, now defunct), one of the dialects Ifriqiyan Arab, relexification from superstrate mainly Sicilian and Italian, to a lesser extent French and more recently English is clear, from the twentieth century, a standard language that has regional varieties or topolectes.

In morphological typology, Maltese is an inflected language that combines bending with internal chips of Arabic to terminations of synthetic languages, Sicilian and Italian. In syntactic typology, Maltese is an SVO language like that is to say that the normal order of the sentence is subject – verb – object.

Maltese is the language spoken in Malta, the islands of Malta and Gozo. At independence, on September 21, 1964, Maltese was proclaimed the national language. Together with English, maltese is one of the two official languages of the country.

Maltese is also one of the official and working languages of the European Union. Maltese is not only the only Semitic language of the European Union but it is also the only Semitic language that is transcribed using an alphabet based on Latin script, however, enriched diacritics as point suscrit or bar included.

History

The Maltese language has the distinction of being simultaneously one of the oldest languages (ninth century) still alive and one of the newer languages (1929) formalized by an alphabet, a spelling and a grammar.

The chrono-cultural framework

Prehistory

The first inhabitants of the Maltese archipelago arrived by sea from Sicily, the neighbouring island (1). Carriers of the culture of ceramics Stentinello, they implanted the Neolithic economy on the islands (2). Their habits were those of the Sicilian shepherds. The flint used to make the stone tools were brought over from Sicily. Lamellae and Obsidian tools reveal imported materials from the islands of Pantelleria and Lipari, off Sicily. In all likelihood, they spoke the language of their origins, that practiced in Sicily, but experts have no information about it.

The evolution of the Maltese population is parallel to that of Sicily. When it passes the Stentinello culture to the culture of Serra d’Alto ceramics and then to the culture of pottery by Diana in Sicily. The culture of Ghar Dalam makes way in Malta to Skorba Gray (4500 -4400 BC.) and later to Skorba red (4400-4100 BC.). The end of the fifth century BC. saw the arrival, always from Sicily, of a new wave of farmers with the culture of San Cono-Piano Notaro pottery – marked by a new funeral rite: the body is placed in a tomb. These newcomers enliven the culture existing in the archipelago. The lithic components of this phase reveal traits from Sicily and Calabria.

The temples period (3800-2500 BC.) reveals a typical Maltese culture impossible to relate to a continental culture (3). The Maltese population, and with it his tongue following for over a millennium and a half an evolution of its own. Attendance at temples and frequent rearrangements are inferred social organization centered on these temples. The temple was also a market place – a place for the redistribution of wealth. This social organization required a complex communication.

This Temple Period ends with the disappearance of the builders of the megaliths circa 2500 BC (4). A new population, imigrated from Sicily, bringing over a culture totally different (5). They revived Maltese civilization slowly repopulating the islands. The archaeological material, weapons in bronze, for example, show that these new inhabitants were Warrior People from of Sicily and South Italy. Around 900 BC. BC a new ethnic group landed on the islands. Their pottery indicates that they originated from the culture of the “pit falls” in Calabria. This population, renewed the link between Malta, Sicily and southern Italy. They will go down in Maltese history as those introducing writing.

Antiquity

“Malta inaugurated the long series of times which made her not only a reflection of the history of others“: with this sentence Alain Blondy summarizes the approach to this phase in the history of the Maltese Archipelago, i.e. according to their colonizers in succession.

At the centre of the Mediterranean, between the eastern and the western basins, in the middle of the strait that separates Sicily from Tunisia, with its high cliffs on the southwest coast and its natural harbours on the north-east coast, Malta is an obvious relay. Classical authors such as Diodorus Siculus, already pointed to the strategic location of Malta on the Phoenician sea routes. (6)

The Phoenicians, great navigators, using Malta as from 10th century BC., as a stopover on their way to fetch copper from the Iberian peninsula. The Mediterranean Sea was the sea of the Phoenicians at that time. They established a colony on the Maltese Islands about 725 BC.

The Phoenicians, great navigators, using Malta as from 10th century BC., as a stopover on their way to fetch copper from the Iberian peninsula. The Mediterranean Sea was the sea of the Phoenicians at that time. They established a colony on the Maltese Islands about 725 BC.

“The inhabitants of Melita is a colony of Phoenicians, who traded up in the western ocean, made a warehouse of this island, its situation at sea and goodness of its ports made it very favourable to them “.

With trade, the Phoenician settlers also brought their own language and alphabet. Through the epigraphic testimony, it is accepted that the name of the island of Gozo (Maltese Ghawdex) comes from the Phoenician Gaulos (registration of II or III century Gawl called the Phoenician settlement on the site of present Victoria ).

The Greeks also settled in the seventh to the fifth century BC. and apparently peacefully shared the islands with the Phoenicians. This implies that the Greek language may have been used on the islands in parallel to the Phoenician.

It was in Malta that two cippi, dated second century BC, were found in the seventeenth century. They were dedicated to the god Melqart, Lord of Tyre and they had a bilingual Phoenician / Greek inscription. In 1758 this enabled a French archaeologist, Father Jean Jacques-Barthlemy, to decipher the Phoenician alphabet.

It is commonly accepted that the name Malta comes from the Greek meli Malta (“Honey”) or melita (“bee”). Melita is also the name by which Malta is still often called in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

With the decline of Phoenicia under the battering of the Assyrians and Babylonians, the Maltese Islands came under the control of Carthage in 480 BC. (7) In 218 BC. the archipelago was conquered, with the help of Maltese, by the consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus. The islands were for several centuries under the control of the Romans who recognized the Maltese as “socii (allies) of Rome. Archaeologists who have studied the Punic and Roman sites in the archipelago all note the persistence of Punic culture. (8) (9)

But the Maltese, eventually adopted the lifestyle and culture of Rome, and perhaps began to practice the language of the Romans, that is Latin (10). It was during this period that the Maltese culture acquired one of its features (11). In 60 AD the Apostle Paul of Tarsus in the company of the Evangelist Luke was shipwrecked on the island (12). This was followed by the conversion to the Christian Religion of the Roman procurator Publius, first bishop of Malta and future Bishop of Athens. The cultural profile of the Maltese population is difficult to identify, inscriptions in Greek, Latin and also in a Punic dialect cannot rule in favour of one language over another for the entire period.(13)

Malta suffered all the vicissitudes of the Roman Empire: the occupation of the barbarians – the Vandals, probably around 445, and the Ostrogoths in 477. But when Sicily was resumed back into the Eastern Roman Empire East in 535, following the action of Belisarius, the islands of Malta and Gozo were incorporated into the empire, l remained so until the Arab conquest in 870 that marked the early Middle Ages.

Middle Ages

Historians have few documents describing the conquest of Sicily by the Aghlabid Arabs. Similarly, the capture of Malta is poorly documented and most documentation is mainly in Arabic and no new source is known since 1975. (14)

Archaeological studies have revealed two phenomena:

1. an enrichment and development of Byzantine trade,

2. Defence setting the site of Mdina in parallel with the rise of Muslim.

The fortress city of Mdina was taken August 28, 870, and demolished. The population was certainly taken into slavery. “After (the conquest) the island of Malta remained an uninhabited ruin.

Historians are still debating this (15), but what is certain is that the island was repopulated by Arab-Berber settlers and their slaves from 440 of the Hegira (1048-1049). At that time, in a Byzantine action on Malta, Muslims offered to free slaves and to share their property with them if they agree to take up arms at their side to counter the attack as actually happened. After the defeat of the Byzantines, the Muslims even allow mixed marriages and the creation of Rahal, freehold landowner field, was the result of this action. (16)

Registration in the fifteenth century gives a list of names of these rahal with an undoubtedly Arab name, demonstrating the widespread use of the Arabic language. One problem remains for linguists: all the names in Maltese, with the notable exception of the name of the islands of Malta and Gozo, is of Arab origin. However, replacement of one language to another has never, in any country, erased all the old gazetteers. Thus Latin has not erased the names Celtic, while in Malta, Arabic place names erased Punic, Greek and Latin.

The Aghlabid occupation ended in 921. The Fatimids in Malta lasted until the Norman Conquest in 1091, more than two centuries. In fact, this Norman victory does not change much in the archipelago. The Normans settled in Sicily and Malta was managed remotely via their barons.

Norman tolerance allowed Muslims to stay put. The Maltese Islands continued to practice Arabic Maltese, the Arabic dialect, which in time will evolve independently of its mother tongue. This is the only plausible explanation for the permanence of Arabic in Malta when it disappears quickly from Sicily during the reign of the Normans.

The 1240 census, one hundred and fifty years after the Norman Conquest, written by a priest, Father Gilbert, counted about 9000 inhabitants in Malta and Gozo, including 771 Muslim families, 250 Christian families and 33 Jewish families. Apparently they all lived in harmony. Maltese poets of that time, Abd ar-Rahmm Ramadan ibn Abd Allah ibn as-Samant, Utman Ibn Ar-Rahman As-Susi nicknamed as Abu Al Qasim Ibn Al Ramdan Maliti wrote in Arabic.

Finally, between 1240 and 1250, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor expelled Muslims and laid the foundation of the Maltese language.

Meanwhile, the Normans gave way to Hohenstaufens in 1194, followed by the House of Anjou in 1266. The Sicilian Vespers in 1282, which drove the Angevin, gave succession to the kings of Aragon. (17) This did not change much else in the archipelago to strengthen links with Sicily. It’s Charles V who closed the Middle Ages by giving Maltese Islands to the Order of St. John of Jerusalem in 1530.

Modern and Contemporary Periods

Charles V gave full sovereignty of the Maltese Islands to the Hospitallers of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem who were driven out of Rhodes by Suleiman the Magnificent on 1 January 1523. (18)

This Order included knights from all over Europe organized by their language (eight). The Grandmasters of the order were mainly French and Spanish, but while the language used by the Order in Rhodes was French, in Malta they started using Italian. They used Tuscan Italian, The Maltese population communicated between themselves in Maltese(19). However the Maltese elites gradually started to repalce Sicilian with Tuscan Italian which was the only written language on the islands. The knights of the Order have also left their mark on the Maltese language. The Order of St John was expelled from Malta in 1798 by Bonaparte, on his way to Egypt, who took possession of the islands on behalf of France.

The French remained in Malta just two years. The Maltese rose against the French after only three months. With the help of the British the Maltese forced the French to capituale in September 1800. This two-year period is not sufficient to explain the incorporation of some French words in the maltese vocabulary. During the time of the Order of St John, especially during the 18th century, French merchant ships were most likely to visit the Valletta Grand Harbour. France was the first country to trade with Malta and the long association of French sailors with the Malese harbour populationbetter explains these borrowings. Many of these sailors also communicated through the lingua franca, a kind of pidgin of the Mediterranean.

The British took possession of Malta in 1800, a situation that was formalized by the Treaty of Paris in 1814. The British colonial administration governed the islands until Independence on 21 September 1964. The Maltese State becomes part of the Commonwealth and a Republic on 13 December 1974.

For a century and a half, the colonizer, besides influencing the economic development and public instruction, managed in 1934 to impose its language as to make English the official language alongside Maltese, but at the cost of a “language war” against the Italian commonly referred to as the Language Question.

History of the Maltese language

Spoken Maltese

The archipelago certainly spoke a language, or a dialect, of Phoenician origins for five centuries and Punic for two centuries, maybe three, together with the ancient Greek for at least two centuries and perhaps Latin for eight centuries. The entire population was certainly not speaking the same language at the same time, and we should distinguish between social and economic pursuits, which document sources do not permit.

In 220 years of occupation, followed by a century and a half of tolerated practice, the Arab occupants have managed to give birth to a dialect of Arabic – Arabic Maltese. Unlike Sicily, who abandoned the Arabic dialect of the former occupiers to find the Latin roots of what is Sicilian, the Maltese supported their dialect on their islands away from their mother tongue or other ifrikiyens dialects. Presumably, the long practice of Phoenician-Punic Semitic languages or dialects predisposed the people to the adoption of Arabic.

Occupants after the Arabs, either were not numerous enough, there were only three villages, Mdina the capital, the Borgo (the commercial port) at Malta, and Rabat in Gozo, or did not exchange with the Maltese population sufficiently to make possible the adoption of another language.

In two hundred and fifty years of Spanish rule, only one sovereign visited Malta and Counts rarely lived there. Consequently Malta’s destiny was linked to Sicily. This promoted the integration of many Sicilian words from immigrants. As when the entire village population of Celano in the Abruzzi was deported to Malta in 1223 by Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, when Count Thomas rebelled against his sovereignity.

During the Norman period, cultural life in Malta and Sicily was expressed in Sicilian-Arabic and was written using the Arabic alphabet. At that time, the Maltese population which was small, a little over 30,000 inhabitants around 1430, found it convenient to use Maltese for oral communicaton and wrote in other languages mainly those used in Sicily. The oldest documents using the Maltese language, or speaking of it, date from the fifteenth century and are found in the notarial archives. Records of notary A. Manuele, dated 1426, referred to Malese as lingwa arabica. In a will dated 1436 of a certain Paul Peregrino, Maltese is called for the first time by its name lingwa maltensi.

In 1966, two researchers, Professor Godfrey Wettinger and Father Michael Fsadni found what is to date the first written record of the Maltese language, a poem attributed to Pietru Caxaro (1410-1485). Old Malteseis used in Il-Kantilena (Xidew il-Qada in Maltese) which was written on the last page of a notarial register. This melody of twenty lines is preceded by five introductory lines in Sicilian and was written between 1533 and 1563 by Brandano, the notary’s nephew Caxaro. In fact it was common practice for solicitors of the time to write their actions in Sicilians, in which they incorporated, according to various spellings, the names of people or places. Numerous examples were found among the papers of notary Giacomo Zabbara dated 1486-1501.

In 1966, two researchers, Professor Godfrey Wettinger and Father Michael Fsadni found what is to date the first written record of the Maltese language, a poem attributed to Pietru Caxaro (1410-1485). Old Malteseis used in Il-Kantilena (Xidew il-Qada in Maltese) which was written on the last page of a notarial register. This melody of twenty lines is preceded by five introductory lines in Sicilian and was written between 1533 and 1563 by Brandano, the notary’s nephew Caxaro. In fact it was common practice for solicitors of the time to write their actions in Sicilians, in which they incorporated, according to various spellings, the names of people or places. Numerous examples were found among the papers of notary Giacomo Zabbara dated 1486-1501.

On January 1, 1523, The Knights Hospitallers of Rhodes were forced out from the island of Rhodes by Suleiman. For them, began a long seven years of wandering. Pope Clement VII intervened with Charles V on their behalf. The Maltese Islands were considered and Grand Master Philippe Villiers de L’Isle-Adam sent a fact finding mission on these islands. The eight commissioners, one from each language, following an inspection in 1524, submitted an unfavourable report to the Grand Master. In this report the commissioners described Maltese ad lingua Moreska.

In 1636, during a trip to Malta, encyclopedic Athanasius Kircher described Maltese as out of the ordinary. He described a population sample of 117 persons, comprising 27 families, living at Ghar il-Kbir (“great cave” in Maltese). Each family had a cave with a place to sleep, another for supplies, and yet another for animals. This population, said Athanasius Kircher, spoke a Semitic language particularly pure (without any Italian influence).

In four centuries, between 1426 and 1829, the publication of Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy in the Journal des Savants, the Maltese had all sorts of qualifications and roots of all kinds had been set. The study for Sacy confirms that Maltese has direct parentage direct of modern Arabic of Ifriqiya through Arabic Maltese.

Linguistic Roots

Many speculate that the search for the roots of the parent language of Malta has always been about even before the decisive progress in linguistics. Below are grouped all the attributes of sonship that the Akkademja tal-Malti (Maltese Academy) lists :

•Arabic in 1426 for A. Manuel, in 1582 for Giovanbattista Leoni, in 1585 for Samuel Kiechel, in 1588 for Michael Heberer von Bretten, in 1636 to Athanasius Kircher ;

•Maltese in 1436 for Paul, in 1533 to Peregrino or Brandano;

•Moorish language in 1524 to the Hospitallers, in 1575 for Andr Thevet;

•Lingua Africa in 1536 for Jean Quintin d’Autun, in 1544 for Sebastian Mnster, in 1567 to Giovanni Antonio Viperano;

•Saracen language in 1558 for Tommaso Fazello;

•Phoenician in 1565 for Gian Battista Tebaldi or in 1809 for Johann Joachim Bellermann;

•Carthaginian language in 1572 or in 1594 Tommaso Porcacchi for Giacomo Bosio, disproved in 1660 by Burchardus Niderstedt;

•Gross corruption of Arabic in 1615 for Pierre D’Avity or 1690 for the Sieur du Mont;

•Barbarous mixture of Moorish and Arabic languages in 1632 for Johann Friedrich Breithaupt;

•Moorish or Arabic language in 1664 for Sir Philip Skippon;

•Arabic dialect in 1668 to Olfert Dapper;

•Mixture of Arabic and Italian in 1694 for Pajol Anselmo;

•Fez Moorish language in 1700 for John Dryden;

•Punic language in 1718 for Johannes Heinrich Maius in 1750 for Gian Soldani, in 1777 for Jakob Jonas Bjoernstah or 1791 for Mikiel Anton Vassalli ;

•Arabic dialect in 1804 for Louis de Boisgelin ;

•Punic language and Arabic in 1810 to Wilhelm Gesenius.

In four centuries, all backgrounds and all similarities with other languages were found in the Maltese language. Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy closed the debate in 1829 by demonstrating in the Journal of the Scholars that Maltese was a descent of Arabic.

First philological argument

Historically, the first linguistic dispute about the Maltese language was on its affiliation with its parent language. Basically there were two main competing theories: Maltese has its origins in Punic or Arabic? There is at least one common point to these two theories: the Maltese language is a Semitic language.

Apart from the writer-travelers, here or there, depending on their attractions, that have written about the Maltese language, we have to wait until 1718 for a German, Prof. Heinrich Johannes who published the Maius Specimen in Lingua Punicae Hodierna Melitensium Superstitionem (A Sample Punic language in its Maltese survival) in which he tries to show the affinity between Maltese and the Punic languages.

The first Maltese to study his language and to declare it origins from Punic was Canon Gian Pietro Francesco Agius de Soldanis, who between 1750 and 1759 published several volumes written in Maltese or Italian. Due to the de Soldanis high reputation in Malta his opinons will bias long subsequent studies. In the second half of 1750s Count Giovanni Antonio Curmi (1696-1778) denounced this theory in an academic paper Melitensium Lingua Punica (Maltese Punic Language). Again in 1809, Johann Joachim Bellermann argued in favour of the theory of Punic origin in Poeniciae lingauae vestigiorum in Melitensi specimen (Remains of the Punic language in samples of Maltese). This was immediately contradicted by the known orientalist Wilhelm Gesenius in Versuch ber die Sprache Maltesische (Essay on the Maltese language), in which he explained the great similarity between Maltese and Arabic.

![]() In 1791, the work of Mikiel Anton Vassalli, later called “the father of the Maltese language, Maltese language linked Maltese to the roots of Phoenician-Punic. His position took more weight since Vassalli was the first holder of the Chair of Maltese and Oriental Languages at the University of Malta, a chair specially created for him in 1825.

In 1791, the work of Mikiel Anton Vassalli, later called “the father of the Maltese language, Maltese language linked Maltese to the roots of Phoenician-Punic. His position took more weight since Vassalli was the first holder of the Chair of Maltese and Oriental Languages at the University of Malta, a chair specially created for him in 1825.

In 1829 in the Journal of learned men, the famous French linguist Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy, while recognizing the importance of the Vassalli work, however, contradicted by demonstrating the Arabic roots of Maltese. In 1839, the same year as the colonial government enacted the Freedom of the press, Don Salvatore Cumbo began publishing the magazine Il Filologo Maltese (The Maltese philologist) dedicated to the study of Maltese. It is in this review that are compiled, issue after issue, in the form of inventory, the Maltese words, Hebrew, Aramaic and Arabic in order to highlight the similarities that exist between all of these Semitic languages. In the early nineteenth century positions are relatively well-marked. On one side a few linguists, generally Maltese, who still supported an origin for the Punic Maltese, on the other European philologists recognized that the Maltese language is of Arabic descent. This will crystallize in the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century around arguments over religious language.

Italian was the language of the Maltese culture together with Latin as the language of the Maltese Church. The language of the colonial administration and army, even when Maltese are enlisted in 1840, is of course the English.

Maltese was the language of the people – farmers and workers. The administration, through successive steps, tried to replace Italian with English wherever it could or even Italian by Maltese. Among others, they tried this replacement in education. The British found an ally in the Protestant Churches and Anglicans who thought it was easier to reach the families by making their propaganda in Maltese. The Catholic church reacted on two counts. The Catholic Church faced a proselytizing Protestant Church and the development of public schools. This became very sensitive to the language problem. In 1847 a Catholic priest, Michelangelo Camilleri, converted to the Anglican Church. He founded an association for promoting Christian Knowledge (“Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge”) and translated the New Testamnent into Maltese using the Vassalli alphabet. In this context part of Maltese Catholics denied that their language may haveany links with the Muslims. Many attempted to demonstrate that Phoenician and/or Punic descent as more “acceptable” to them. This problem resulted in a radicalization of linguists and writers who wanted to expunge Maltese of all its “Romance” acquisitions (to avoid Italian) by adopting a purist way described as “smitisante” (to avoid Arabist) in their grammar attempts . This is reflected even today, almost 90 years after the formalization and the publication, in1924, of Taghrif fuq il-Kitba Maltija (information on the writing of Maltese), on rules of writing Maltese. Many Maltese still fail to believe that the Maltese has Arab roots and not Phoenician-Punic.

Written Maltese

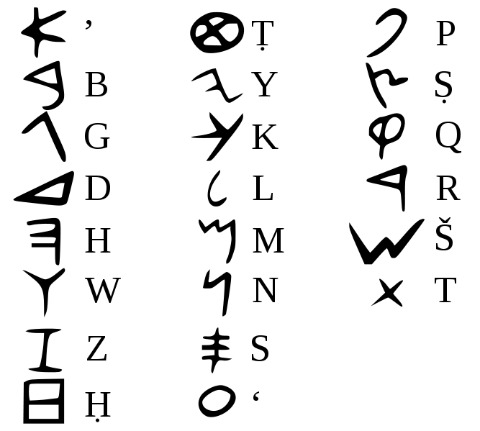

Maltese in the eleventh and twelfth centuries was written using the Arabic alphabet, as shown by the Maltese poets of this period as for example Ibn Abd ar-Rahmm Ramadan

The dichotomy that took place in the Maltse society during the following centuries made Maltese to lose all the characteristics of a written language. During the Feudal System, the aristocracy used Sicilian while the rest of the population, became unalphabetisant. It was not until the creation of a bourgeoisie and the openness to trade that some of the Maltese elite opened to a perception of a nation whose language is obviously one. The best example of this movement is given by the patriot Mikiel Anton Vassalli. He opposed the Hospitallers, welcomed the French and challenged the British. Vassalli spent long years in exile, first in Italy then in France, before returning to Malta to get the first chair of Maltese and Arabic at the University of Malta and to finally be distinguished as the “father of the Maltese language. “The willingness of some Maltese to take their mother tongue in social recognition was first animated by romantic ideas and ideals of the French Revolution “but he still had to find a way so that Maltese could be written before becoming a literary language. And through Vassalli we have the birth of an alphabet. The long maturation of this, almost two centuries, between 1750 and 1929, demonstrates the difficulty of the enterprise.

Since the first proposal of Gian Pietro Francesco Agius de Soldanis in 1750 then in 1827 Stefano Zerafa, through the multiple alphabets Mikiel Anton Vassalli between 1790 and 1827, culminating in 1921 in the alphabet of Ghaqda tal-Kittieba tal-Malti (Association of Maltese Writers)(20), the path was a long one.

Maltese Grammar

Along with a script, you also need a grammar to fix the spelling. De Soldanis’ Descrizione della Lingua Punica (Description of the Punic language) and Nuova Scuola di Grammatica (New Course grammar) are the first to lay the foundations for a written grammar published in 1750. Between 1755 and 1759 he published two other studies, one in four volumes written in Maltese Damma-tal Kliem Kartaini Imxerred Fomm fil-Maltin u l-tal-Gawdxin (Compilation of Carthaginian words used in oral and Malta in Gozo) and the other in Italian Nuova Scuola lingua Punica dell’antica scoperta nel moderno parlare e Gozitano Maltese (New study of the ancient Punic language found in the modern talk of Maltese and Gozitan). De Soldanis cites two of his predecessors whose texts are lost, Fra Domenico Sciberras, Bishop of Epiphany of Cilicia and the Knight of Malta De Tournon. It was during his exile in Rome in 1791 that Vassalli publishes his first grammar il Mylsen – Phoenico Punicum-sive Grammatica Melitensis (Mylsen – The Phoenician-Punic grammar or Maltese). He published other studies. In 1796 the Lexikon (Lexicon). Above all it is through his academic work, from 1825, after his return from exile in France, that Vassalli leaves his mark on the language. In 1827 he published Grammatica della lingua Maltese (Grammar of the Maltese language).

In 1831, Francesco Vella published for the first time in Malta, a Maltese grammar in English for the British, Maltese Grammar For the Use of the British. In 1845 Canon Fortunato Panzavecchia published a grammar greatly inspired by Vassalli’s Grammatica della Lingua Maltese (Grammar of the Maltese language). The consul Vassily Basil Roudanovsky, stationed in Malta, published in 1910 A Maltese Pocket Grammar (A grammar of Maltese pocket).

Since its inception in 1920, Ghaqda Kittieba tal-Malti ( Society of Maltese Writers) got to work. It presented an alphabet in 1921 and in 1924 a grammar and spelling rules: Tagrif fuq il-Kitba Maltija (Information on the writing of Maltese), mostly written by Ninu Cremona and Gann AntonVassallo. Alongside its work with the Society, Ninu Cremona released his own English grammar A Manual of Maltese Orthography and Grammar (Handbook of spelling and grammar Maltese).

In 1936 Jesuit Father Edmund Sutcliffe published A Grammar Of The Maltese Language (Grammar of the Maltese language). It is recognized as the best ever Maltese grammar written by a non-Maltese. In 1960 and 1967, Henry Grech published two volumes Grammatika tal-Malti (Maltese Grammar). A Maltese grammar reference today is that of Albert Borg and Marie Azzopardi-Alexander published in 1997 under the title of Maltese, Descriptive Grammars.

Maltese Dictionaries

After the alphabet and grammar, there is one final aspect of the written language – the vocabulary, usually grouped in a dictionary.

The first known person to show interest in the Maltese language is German Hieronymus Megis who travelled to Malta in 1588 and 1589. He collected Maltese words in 1603 which he published with their translation into German by the name of Polyglottus Thesaurus (multilingual Treasury) then Propugnaculum Europae (Bulwark of Europe) in 1606.

Another list of 355 words was published in 1664 with a transaltion to English by a British traveller Sir Philip Skippon under the title Account of a Journey Made Thro ‘Part of the Low Countries, Germany, Italy, and France. In an edition of 1677 of the Notitia vocaboli ecclesiastici (Notice of ecclesiastical vocabulary) named Hierolexicon (Dictionary of Jerusalem), Domenico Carlo Magri gives the etymology of certain Maltese words.

The first dictionary of the Maltese language is written by a French Knight of the Order of St John, Francois de Vion Thezan Court in 1649. This dictionary is only known by a modern edition of Arnold Cassola, 1992, under the name Regole per la Lingua Maltese (Rules for the Maltese language), and includes a leading number of instructions for the soldiers of the Order in Italian and Maltese. Cassola also published the first part of the dictionary (the second is lost) Maltese-Italian composed by Fr Pelaju (Bartolomeo) Mifsud. These works were followed a century later, between 1755 and 1759, by that of de Soldanis Damma tal-Kliem Kartaini Imxerred wire Fomm Maltin tal-l-u Gawdxin (Compilation of Carthaginian words used in spoken in Malta and Gozo ) which, as its name suggests is a compilation rather than a dictionary. In fact the first relatively complete dictionary, with 18,000 Maltese vocabulary words was published in 1796. It is the work of Vassalli titled in Latin Lexicon Melitense Italum (Dictionary Maltese-Latin-Italian). Note that the first Maltese language dictionaries are often if not always, accompanied by the vocabulary of another language. Vassalli as a patriot, who fought all his life to impose the Maltese does not mind putting the Maltese language alongside Italian. This characteristic has persisted until now, where the Maltese dictionaries are bilingual dictionaries, English-Maltese. Though today we have Aquilina’s dictionary which is Maltese-Maltese.

The first dictionary of the Maltese language is written by a French Knight of the Order of St John, Francois de Vion Thezan Court in 1649. This dictionary is only known by a modern edition of Arnold Cassola, 1992, under the name Regole per la Lingua Maltese (Rules for the Maltese language), and includes a leading number of instructions for the soldiers of the Order in Italian and Maltese. Cassola also published the first part of the dictionary (the second is lost) Maltese-Italian composed by Fr Pelaju (Bartolomeo) Mifsud. These works were followed a century later, between 1755 and 1759, by that of de Soldanis Damma tal-Kliem Kartaini Imxerred wire Fomm Maltin tal-l-u Gawdxin (Compilation of Carthaginian words used in spoken in Malta and Gozo ) which, as its name suggests is a compilation rather than a dictionary. In fact the first relatively complete dictionary, with 18,000 Maltese vocabulary words was published in 1796. It is the work of Vassalli titled in Latin Lexicon Melitense Italum (Dictionary Maltese-Latin-Italian). Note that the first Maltese language dictionaries are often if not always, accompanied by the vocabulary of another language. Vassalli as a patriot, who fought all his life to impose the Maltese does not mind putting the Maltese language alongside Italian. This characteristic has persisted until now, where the Maltese dictionaries are bilingual dictionaries, English-Maltese. Though today we have Aquilina’s dictionary which is Maltese-Maltese.

Malta became a British possession in 1800, but it was not until 1843 for a first dictionary Dizionario portatile delle lingue maltese, italiana e inglese (portable dictionary of Maltese, Italian and English) thanks to Francesco Vella and 1845 to Giovanni Battista Falzon with Dizionario Maltese-Italiano-Inglese (Dictionary Maltese-Italian-English) which was reprinted in 1882 with an grammatical addition. They were followed in 1856 by the Piccolo Dizionario Maltese-Italiano-Inglese (Small Dictionary Maltese-Italian-English) of Baron Vincenzo Azzopardi which was the first dictionary to be introduced into public schools. In 1885, Salvatore Mamo published English Maltese Dictionary (English-Maltese Dictionary). Anecdotally, it was not until 1859, in the book review of Cesare Vassallo, librarian at the National Library of Malta : Catalogo dei Codici e Manoscritti inediti che nella pubblica conservano biblioteca di Malta (catalog codes and unpublished manuscripts that are preserved in the Public Library of Malta) What appears a Vocabolario Inglese-Italiano-Maltese Vocabulary (French-Italian-Maltese) to the unknown author.

The first addition is tempted by E. Magro in 1906 with the publication of Franais and Maltese Dictionary from A to L (Maltese and English Dictionary: A to L) but the second volume never appeared. Then in 1921 began publishing the first volume of mill-Dizzjunarju Eniklopediku Inglizi gall-Malti u mill-Malti gall-Inglizi (Encyclopedic Dictionary of the English to Maltese and Maltese to English) by Vincenzo Busuttil and Tancred Borg. A work of twelve years due to a volume per year since the last and twelfth volume appeared in 1932. In 1942, Erin Serracino-Inglott began writing his dictionary of Maltese, but the first ten volumes of his short-Miklem It Malti (Maltese Words) does not appear until 1975 and was completed shortly before his death in 1983. His estate will be taken by Guze Aquilina, second holder of the Chair of Maltese and Oriental Languages at the University of Malta from 1937 to 1976, 112 years after Vassalli, which publishes the 1987-1999-Maltese Dictionary Franais ( Maltese-English dictionary) in 2 volumes and 80 000 admissions and Franais-Maltese Dictionary (English-Maltese Dictionary) in 4 volumes and 120 000 admissions. Today is a dictionary, in its edition Concise Maltese-Franais-Maltese Dictionary (Collins Concise Maltese-English-Maltese), usage examples and citations have been omitted, which is perhaps the most widely used dictionaries Maltese. Purists, however, accuse him of not always follow the rules of the Academy Maltese.

Maltese Encyclopedias

The encyclopedia used in Malta are all encyclopedias language English, it was not until 1989 that the Nationalist Party created a publishing company PIN – Pubblikazzjonijiet Indipendenza (“Independence Publications”) and ten more years, until 1999, that the first encyclopedia in Maltese Maltese to emerge. The Kullana Kulturali is composed of volumes, each of which addresses a specific topic. In 2006, the encyclopedia was composed of 74 volumes.

Literary Maltese

As already indicated, the oldest document written in Maltese, in its earlier form, is a melody to twenty -Kantilena it, the oldest witness is a witness poetic. This document created in 1450, gives a good idea of what could be spoken Maltese. It was not a crude language allowing only communication tool. In 1585, the inquisitor in Malta burned songs written by a Dominican priest, Pasquale Vassallo, on the pretext of content too libertine.

It’s in the book Dell’Istoria della Sacra Religione and Illustrious Militia di San Giovanni Gierosolimitano (From the history of the Holy and Illustrious Religion Militia of St. John of Jerusalem) of Giacomo Bosio, a historian of the Order, that one can find the first sentence written and printed in old Maltese. Bosio Reports about an old Maltese, who said at the laying of the foundation stone of Valletta in 1566: “Legi in Zimen fait Wardia neck CSBS raba EUISS Uquia”, giving Maltese modern “wire JIGI mien li kull-Wardija xiber raba ‘JISWA uqija “(Is it time to Wardija where every inch of land is worth an ounce).

Maltese Poetry

After the melody of the fifteenth century, the first poems ever known in Malta date from the late seventeenth century and the eighteenth / Sup> century. In 1672 or 1675, it seems that Giovanni Francesco Bonamico has translated from French to Maltese poem Lill-Granmastru Cottoner (The Grand Master Cottoner). In 1939 Ninu Cremona published a poem dating from 1700 Jaasra Mingajr tija (Poor boy without guilt) quoted by De Soldanis in 1750.

After the melody of the fifteenth century, the first poems ever known in Malta date from the late seventeenth century and the eighteenth / Sup> century. In 1672 or 1675, it seems that Giovanni Francesco Bonamico has translated from French to Maltese poem Lill-Granmastru Cottoner (The Grand Master Cottoner). In 1939 Ninu Cremona published a poem dating from 1700 Jaasra Mingajr tija (Poor boy without guilt) quoted by De Soldanis in 1750.

Maltese Biblical Literature

The first book printed in Malta’s history of publishing is actually bilingual, since in light of the Maltese text, it contains the text Italian. It is printed in Rome in 1770 at the request of the bishop of Malta Paolo Alpheran Bussan so it is a religious book, actually a catechism Taglim Nisrani (or just Christian Teaching Catechism). It is the translation of Dottrina Cristiana (Christian Doctrine) of Cardinal Bellarmine made by Abbot Frangisk Wizzino. In 1780, appeared at the request of Bishop Vincenzo Labini, this time entirely in Maltese, Kompendju tat-Taglim Nisrani (Condensed Catechism of Christian teaching or condensed). Production of religious literature in Maltese will not cease. In 1822, the “Bible Society in Malta (” Society of Biblical Malta) is the origin of the translation by Marija Guzeppa Cannolo Vanelu Il-ta ‘San Gwann (The Gospel of St. John), the alphabet are not yet set, this gospel is translated with the Latin alphabet from Arabic letters mixed. The same company publishes, after the death of Vassalli, his translations of the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles.

As already mentioned the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge published in 1847, he Testment did ( New Testament ) the pastor Michelangelo Camiller. In 1924, Guze Musact Azzopardi finished his translation of the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles began in 1895 and in 1929 began regular publication of 72 books of the Bible performed by Pietru Pawl Saydon from Greek texts. This publication ends thirty years later in 1959. The tal-Kummissjoni Liturika Provinja Maltija (Liturgical Commission of the Maltese Province) beginning in 1967 the printing of liturgical texts in Maltese to complete its task in 1978 with the New Testament. Following the council Vatican II the Malta Bible Society decided to make a new translation of biblical texts in an ecumenical perspective. Finally in 1984, they published another edition according to the sources, which gathered in one volume all the biblical texts. This work was performed under the direction of Dun Karm Sant aided by many researchers. Dun Gorg Preca created in 1907, the Socjeta’ tal-MUSEUM (MUSEUM society) The society discussed in Maltese all subjects of Theological nature including Ascetic, Moral and Dogmatic topics.

Maltese Literature

The first work of the mind purely literary writing in the Maltese seems to be a novel by a professor Neapolitan Giuseppe Folliero de Luna (maternal grandfather of Enrico Mizzi ) Imabba Elvira jew ta ‘tyranny (Elvira or love of Tyrants) whose 1863 publication date is not guaranteed. Cons by the date of 1887 is sure to publish the first novel of historical genre-Maltese especially from the pen of Don Amabile NHIS, the series is named Ward Bla Xewk (Roses without thorns). Then from 1901 to 1907, is a collection of stories published X’Jgid il-Malti (Maltese What say) written by Father Manwel Magri in a collection called tal-Kotb Mogdija ta-mien (Books over time ) and will last until 1915. C’est en 1909 que u Muscat Azzopardi publie son premier roman ( ). It encourages Dun Karm Psaila writing in Maltese and it made a first attempt in 1912 with Quddiem Xbieha tal-Madonna (facial image of the Madonna). His first work will be published in 1914 in the number 140 in the series of books over time as the L-Ewwel Ward (First Roses). In 1922, Dun Karn wrote the lyrics of L-Innu Malti (Malta Hymn), which became the official anthem of Malta. Dun Karm is called the first “national poet” in 1935 by Laurent Ropa.

Alongside writing, translation into Maltese of great literary works began in 1846 by a popular work since it is the Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe. The second literary translation is the Divina Commedia ( Divine Comedy ) by Dante for the Maltese who have special attention. The first translation in 1905, it is the result of the work of Alfredo Edoardo Borg. The second translation is the work of Erin Serracino-Inglott in 1959 and in 1991, Alfred Palma gives a third in the Maltese translation of the Comedy. Finally, we can also quote Victor Xuereb, delivering in 1989 a translation of the Odyssey of Homer.

The colonial government recognized the Maltese in 1934 and in the same movement is taking steps to expand its use. Outside the areas which are normally its own, in 1935 he launched a competition for novels. In 1937, the results are made public and the winner is found to be Guze Aquilina with Tliet Saltniet Tahta (Under three kingdoms). In 1939, is noted for the first time by a Maltese literary criticism novel, this is Alla ta-gaag (Youth of God) Karmenu Vassallo. In the 1960s, Joseph J. Camilleri was seen as best writer Malta with what is cited as his best novel Sinjuri Ahna (We Women) or his poetry Kwartet (Quartet). Were then also noticed Victor Fenech, Daniel Massa or Charles Vella for modern poetry. It is time, 1966, begins a long controversy in the media of the time between “modern” and “old” maintained by the MQL – Moviment Qawmien Letterarju (Literary Renaissance Movement) which was headed by Charles Coleiro and published a journal, Polz (Pulse). In 1974, the MQL launches first literary prize in cooperation with the firm Rothmans. The prize is awarded to Frans Sammut’s novel Samuraj (Samurai). The same year also created the literary prize Phoenicia. Trevor Zahra Tahta with it-tal-Palm Weraq (Sub palms) wins the Klabb Kotb Maltin (Maltese Book Club). In 1991, Joe Friggieri, with L-Gerusija (The broken engagement), won the first competition of new, founded by the Gaqda Bibljotekarji (Library Association).

Maltese Theatre

Since the construction of Valletta in 1731, a theater commissioned and funded personally by Antnio Manoel de Vilhena, Grand Master of the Hospitallers, Malta has always had a scene. Time of the Hospitallers, were often knights who rode and played classical pieces French or Italian. In 1843, there is at least one other theater in Birgu, Vittoriosa theater. The year 1866 was inaugurated in Valletta a new hall, the Royal Opera House (ROH). But at the Manoel Theatre that played the first play written by a Maltese Maltese (1836), Katarina, a drama written in verse by Luigi Rosato and published in 1847. Several of his other works are produced in this theater the following years. In 1913, Ninu Cremona wrote it-tal-Fidwa Bdiewa (Redemption farmers), this piece is considered the first piece of classical theater Maltese. From 1856, the Compagnia Filodrammatici Vittoriosa (Company philo-dramatic Vittoriosa) of Pietru Pawl Castagna is the first company to make his repertoire Maltese language.

In 1946, Nikol Biancardi based Gaqda Maltija Bajda u Hamra (red and white Maltese Association “) and organized the first” theatrical Maltese Contest “at Radio City Opera House (Opera Radio City”) of Hamrun. After its dissolution in 1950, Erin Serracino-Inglott creates KOPTEM – Kumitat Organizzatur gat Privat-Teatru Malti Edukattiv (“Committee of private educational theater organization Maltese) to continue the organization of theatrical competitions. After creating the Compagnia Filodrammatici Vittoriosa, this year sees three new theatrical planned: The Malta Drama League (“League Maltese drama”), “Maleth” at the instigation of Anthony (iNOS) and Ghirlando Drammatika Gaqda tal- Malti – Universit (“dramatic Maltese Association – University) Professor Guze Aquilina. In 1962, the Manoel Theatre which is organizing a competition and drama that will reveal who will be considered the greatest playwright of Malta. After a first appearance in a theatrical competition in 1950, with fix-cby Xemx (Mist in the sun), Francis Ebejer won the support of the Manoel Theatre with its parts Vaganzi tas-Sajf (Summer holidays). In 1966, he won two first places in the same competition with Menz and Il-Hadd fuq il-Bejtja (Sunday on the roof).

Standard Maltese

Maltese Edition

The Hospital in the eighteenth century had established control over the issue through a monopoly on the printing. Implementing a control system equivalent, the British colonial administration almost always refuses any authorization to create a print. CMS – Church Missionary Society (Church Missionary Society “), an organization Anglican based in London requires a permit to install a printing press in Malta. This print books proselytes in Arabic for the entire Middle East. She obtained the agreement in 1825 provided that all printed materials are actually exported from Malta. The British colony is quickly becoming a center of printing in Arabic that participates in the literary revival of this language in the nineteenth century. CMS obtained piecemeal permission to print to the archipelago. So it prints some books Mikiel Anton Vassalli Grammatica della lingua as the Maltese (Grammar of the Maltese language) in 1827 or Percy Badger as his Description of Malta and Gozo (Description of Malta and Gozo) in 1838. She obtained the freedom of impression when the colonial administration introduced the Freedom press in 1839 but closed in 1845 when the parent company in London has financial difficulties.

After 1839, it is possible for all Maltese to open a publishing company. The first to do so is AC Aquilina creating in 1855 the oldest publishing house purely Maltese “AC Aquilina & Co. Ltd”. In 1874, Giovanni Muscat opened a bookstore to commercialization of literary production in Maltese and English. He quickly add software to its business distributing a production activity with a publishing house.

The copyright in printed literature are established in Malta in 1883.

Media

In 1839, the colonial government proclaimed the freedom of the press. Before that date no regular publication was authorized by the administration. “Malta” was the first newspaper published by George Percy Badger followed by “Il Filologo Maltese” (The Maltese philologist) published by Dom Salvatore Cumbo. From 1941 Badger published in his newspaper an article on Maltese in education. In 1846 Richard Taylor published the “Gahan” until 1861 with an interruption between 1848 and 1854.

The first newspaper in Maltese to be published outside Maltese territory was “Il-Bahrija”. This newspaper was published in 1859 in Egypt which at the time was a French Colony.

The first issue of the almanac “Il-Habib Malti” (The Maltese Friend) was released in 1873. The celebrated almanac “Il-Pronostku Malti” was published for almost a century by Giovanni Muscat from 1898 to 1997.

Guze Muscat Azzopardi published “In-Nahla Maltija” (The Bee Malta) from 1877 to 1879. In 1913 Pawlu Galea revived “Il-Habib” (The Friend) till 1928. It is in this newspaper that Napuljun Tagliaferro published a controversial article “Ilsien l-Malti u l-Marokkin” (The Maltese and Moroccan language). In 1926 Azzopardi published another newspaper “Il-Kotra” which stopped in 1933.

Amid this intellectual agitation the media emerged in support of political positions as “Il Mediterraneo” (1838-1902), “The Malta Times” (1840-1904) and “Il Corriere maltese”. Some Newspapers supported a liberal opinion such as “L Ordine” (1847-1902) or were of Catholic inpsiration. In 1880, Fortunato Mizzi, the father of Prime Minister Enrico Mizzi, published at the same time the Nationalist Party’s newspaper “Malta”.

Clashes between supporters of different alphabets were spread in the press and in 1903, Dimech wrote regularly in his journal “Il-Bandiera tal-Maltin” (The flag of Malta) to denounce the manoeuvres of the opponent supporters of the English and Italian languages to the detriment of the Maltese language.

It is through the press that a crucial turning point for the future of the Maltese language was taken. The appeal of a young 21 year old man, Frangisk Saver Caruana, was sent to the newspaper “Il-Habib” on 7 Sptember 1920. He called for the creation of a new union of Maltese writers.

Finally on November 9, 1920, appeared a notice: “il-Hadd li Nhar gej, 14 ta ‘Novembru, fi-ghaxra nofs u ta’ filghodu, issir laqgha l-ewwel ta’ Ghaqda Cirkolo ta’ l- Unjoni ta’ San Guzepp il-Belt, 266 Strada San Paolo “(next Sunday, November 14, at 10.30 am the first meeting will be held of the Society of St. Joseph Circle in Valletta, 266, Saint Paul Str). Over thirty people were present, a commission was quickly established quickly and took the name Ghaqda tal-Kittieba tal-Malti (Maltese Writers’ Association). On 18 December 1921, after 17 sessions, the Association proposed an alphabet. The Maltese press played a key role in transforming the spoken Maltese to written Maltese, although it will still take almost fifteen years for the formalization of Maltese instead of Italian.

A year after the formalization of Maltese on 1 January 1934, the Maltese could listen r for the first time a Maltese broadcast and in 1939 began the dissemination of literary programs. The first radio drama in Maltese was an adaptation by Vella Haber in 1943 of Sir Temi Zammit’s work. Finally in 1962, MTV – Maltese television – started broadcasting its first television broadcasts.

Maltese as a national language

In the mid-eighteenth century there were a few enlightened minds, such as Gian Francesco Agius de Soldanis and Mikiel Anton Vassalli, who wanted to turn their spoken only language spoken into a literary language until the initiative of Frangisk Saver Caruana in 1924 which gave birth to the Ghaqda tal-Kittieba tal-Malti will lead to the creation of an alphabet, grammar and spelling.

Political agitation from the 1880s that made the language problem one of its symbols in 1883. The Maltese upper classes, who all practiced Italian, wanted to keep their benefits and did not want to provide a gateway to the petty bourgeoisie. They found political support from nationalists who saw a better future for the archipelago from the Italian neighbours rather than with the distant colonial British. This opposition has often been called “language conflict”. This conflict lasted until the middle of the twentieth century.

The Maltese language finally became the official language of the archipelago in 1934, alongside English. Since then, English remained an official language, but the national language of Malta is Maltese as stated by the constitution.

Article 5 of the Constitution states that:

“(1) The National language of Malta is the Maltese Language.

(2) The Maltese and the English languages and such other language as may be prescribed by Parliament (by a law passed by not less than two-thirds of all the members of the House of Representatives) shall be the official languages of Malta and the Administration may for all official purposes use any of such languages:

Provided that any person may address the Administration in any of the official languages and the reply of the Administration thereto shall be in such language.

(3) The language of the Courts shall be the Maltese language:

Provided that Parliament may make such provision for the use of the English language in such cases and under such conditions as it may prescribe.

(4) The House of Representatives may, in regulating its own procedure, determine the language or languages that shall be used in Parliamentary proceedings and records..”

Literary Institutions and control bodies of the Maltese language

The initiative of Frangisk Saver Caruana, who made an appeal on 7 September 1920 in the newspaper “Il-Habib”, caused the setting up of the Ghaqda tal-Kittieba tal-Malti . This association gave Malta its first written language by creating an alphabet, grammar and spelling. But it also gave a literature. Its members were the most important writers such as Dun Karm Psaila – the national poet. Besides being a noticed writer noticed he was the author of the national anthem.

It was during a general meeting on May 7, 1922 that the Association was officially set up. The aims were:

1.Ensure the development of the alphabet, grammar and spelling;

2.Ensure the protection and rights of the Maltese language;

3.Promote dissemination of the language and literary works while preserving the Catholic religion.

In 1924 the Ghaqda presented the rules that made Maltese a true language. It also encouraged literature and on 1 November 1924 appointed a commission composed of Frangisk Saver Caruana, Guze Darmanin Demajo and Vincent Mifsud Bonnici with the aim to prepare “Il-Malti” (Maltese), a literary magazine presented on December 21, 1924. It was published on a quarterly basis for the first time in March 1925.

In 1944 a law was promulgated establishing the Kunsill Centrali tal-Malti (Central Council of Maltese) to protect and promote the Maltese language and literature. The Council consisted of representatives of all organizations in Malta. In 1950 the Kunsill ta ‘l- Awturi Maltin was set up. In 1962, the Gaqda Kittieba Zghazagh was setup and in 1969 became the Grupp Awturi. In 1998 the Ghaqda Bibljotekarji was was setup in 1998. In 2001 the Kunsill Nazzjonali tal-Ktieb (National Book Council) was set up.

In 1964 The Association of Maltese writers became the Akkademja tal-Malti (Maltese Academy), and in 2005, the government discharged them from the surveillance Maltese Language to enable them to devote themsleves completely to the promotion of literary language. As a consequence the Government created the Kunsill Nazzjonali tal-Ilsien tal-Malti (National Council of the Maltese language). This Council is responsible, inter alia, to promote the national language, the definition of spelling and vocabulary, and the implementation of an appropriate language policy.

Linguistic Conflict

The Maltese remembering the promises made by Alexander Ball demanded more freedom from the British Colonial Government. The first freedom to be granted was the freedom of the press, but newspapers pushed for a self-government. The Maltese took the opportunity of the 1847 carnival to press the colonial government for a form of self-government. On May 11, 1849 a new constitution was granted allowing elected Councillors to give their opinion on matters except those regarding the defence of the islands.

After the Unification of Italy some maltese showed their interest in the new neighbouring kingdom. Fortunato Mizzi, the father of Enrico Mizzi, founded the Nationalist Party, and when he got a majority in the elections of 1883, the colonial government raised the stakes by announcing the replacement of Italian in public schools by the English and Maltese. The Councillors of the Nationalist Party resigned and were triumphantly re-elected. The arrival of Gerald Strickland and the establishment of a truly representative government calmed the situation. But the emergence of the language problem re-emerged when Strickland decided to introduce English in the courts. The confrontation was inevitable when an order of 1901 allowed parents the choice of examination language for their children between the Italian and English.

When the Councillors refused to approve the budget for public instruction, letters patent of June 3, 1903 abrogated the 1887 constitution. A commission of inquiry did not help in promoting English in the lower courts and the choice between English and Maltese in the criminal courts. The First World War calmed the conflict. After the war linguistic and political problems remerged.

In 1917 Enrico Mizzi became Leader of the same party that his father had founded in 1880. His pro-Italian behaviour resulted in a court martial which sentenced him to one year imprisonment. He was pardoned at the end of the war and resumed his activity. The Sette Giugno (June 7, 1919) violent riots broke out. The British flag was burned, the army fired killing four people, Wenzu Dyer, Manwel Attard, Giuseppe Bajada, besides some fifty wounded persons. A new constitution was granted in 1921 with the establishment of a parliament that could handle everything except reserved areas and the language issue was part of the reserved areas.

On April 25, 1932 Lord Strickland removed Italian from public education and Law Courts. Mizzi won the elections in June 1932 and as minister of public education on August 6, 1932 tried to reintroduce Italian as a medium of instruction at public schools. However the colonial government took the matter in hand and cancelled the measures imposed by Mizzi in public schools.

On 1 January 1934, the colonial government put an end to language issue by publishing in the Gazzetta tal-Gvern (The Government Gazette) a legal notice stating that the official alphabet and spelling was to be that adopted by the Ghaqda Kittieba tal-Malti. The Maltese language was declared as official language together with English instead of Italian. The constitution of 1921 was repealed in 1936 and the Istituto Italiano di Cultura was closed. The language dispute totally ended during the Second World. The teaching of Maltese became compulsory by 1946.

Features

A language is the reflection of the history of its speakers. Maltese, spoken in the XXI century in the Maltese Islands is the reflection of part of Maltese history. The rich Phoenician culture, Punic civilization and Greco – Roman, have left little trace in Maltese Archaeology. The islands that have created the oldest monuments of human history in the world (sixth millennium BC.) also spoke a language. However today’s spoken Maltese does not reflect these cultures.

Lexical Borrowing

The Maltese language is marked by a variety of lexical origins – three major families of differing importance: Semitic origins, Romance, mostly Sicilian and Italian, and Anglo-Saxon additions. Aquilina believes that non-Semitic loans outnumber the Arab background but the study samples by Fenech shows that the use of this substance is more important than the contributions by Romance. The sample shows an average use of literary words of Arabic origin of 94%, it drops to 86.5% for spoken Maltese to 73% in print and falls to 64% in advertising. The use is about 5% to 8% for literature and for spoken Maltese 4.5% for Italian and 0.4% for English.

Semitic Origins

These are three characteristics common to Semitic languages and Maltese.

Trilitteral Root

The first characteristic of a Semitic language is its morphology. All Semitic languages have a vocabulary built on a lexeme usually triliteral (three letters), sometimes quadrilitteral (four letters) or bilitteral (two letters).

Internal Bending

A second morphological feature that Maltese is Semitic in its roots is the character internally inflected with the kind of numbers by internal breaking. The inflected forms are less numerous in Maltese than in other Semitic languages. Maltese has maintained eight main forms.

•The word “book” in singular ktieb bends in the plural Kotba.

•”Book” in Arabic kitabon in the singular and kutub in the plural.

Pronunciation

Maltese is a rebuilt language. It was a spoken language only, until enlightened minds have sought to make it into a written language and for literature. The pronunciation of the language was thus a working basis, but with an additional difficulty. A Semitic language, a dialect of Arabic is written with a Latin alphabet. It took about two centuries to complete this project.

Phonology

After multiple attempts to create an alphabet, a study committee headed by Ghaqda Kittieba tal-Malti took up the issue and eventually proposed an alphabet based on the basic principle of the phonology, a grapheme = one phoneme. This alphabet has 25 letters in 30 phonemes.

Phonetics

The articulation of the Maltese language is about 8 points and 7 modes of articulation, 10 taking into account the pronunciations which are weak or strong.

Spelling and grammar

The spelling and grammar of the Maltese language were established in 1924 by the Ghaqda Kittieba tal-Malti which petitioned the colonial government to publish the rules as the Taghrif fuq il-Kitba Maltija. This association, which was renamed in 1964 as Akkademja tal-Malti (Maltese Academy), guarded its prerogatives in the preservation of the Maltese language.

A first modification of these rules were issued in 1984 under the name of Zieda ghat-Taghrif . A second amendment was made in 1992 under the name of tat-Aggornament Taghrif fuq il-Kitba Maltija (Updated Information on the writing of Maltese).

In 2005, the government created an overseeing authority for the Maltese language KNLM – Kunsill Nazzjonali tal-Ilsien Malti (National Council for the Maltese language). In 2008 KNLM published Decizjonijiet 1 (Decisions 1) – the latest update for spelling and grammar in Maltese.

___________

Notes

1.The earliest traces of these pastors are mainly found in the cave of Ghar Dalam. Their presence is dated 5400 BC. This period is known as Ghar Dalam (5400-4500 BC.).

2.The site of Zebbug to the center of the island of Malta was the first to uncover graves in wells dug in the limestone. Zebbug gave its name to the first phase (4100-3800 BC.) Temple Period

3.Lord Colin Renfrew sees these temples “the expression of differentiated communities. The size of the temples, the size and weight of the stones used to build them require a social organization. Given the characteristics of the Maltese archipelago, Tagliaferro relates the assumption that there must be at least six distinct social groups, comprising between 1,500 and 2,000 people each, of about a population of 10,000 inhabitants. Sardinian Archeologist Giovanni Lilliu asked the question, given the small size of the archipelago and the importance of the Temple of Tarxien, whether the prehistoric Maltese society had made the leap from one form of political unity. He believes that political and religious powers may in part be confused, the “high priest” to be a “prince”.

4.The commonly accepted explanation is that an unsustainable land and resource depletion was forcing people to abandon the Maltese Islands.

5.This is the Bronze Age Malta (2500-725 BC.)

6.”The first is the island of Melita, eight hundred stadia distant from Syracuse and has several ports which are very advantageous. The inhabitants are very rich. They apply to all sorts of trades, but mostly they do a great trade in extremely fine paintings. Houses of this island are beautiful decorated and roofs that are all plastered. The inhabitants of Melita is a colony of Phoenicians, who traded up in the western ocean, made a warehouse of this island, its situation at sea and goodness of its ports made it very favourable for them. This is also what many traders see every day at Melita, which reported its inhabitants so rich and famous. The second island is called Gaulos, adjacent to the first, and yet completely surrounded by the sea. Its ports are very convenient, it is also a colony of the Phoenicians. ”

7. In 814 BC. AD, they created their colony of Carthage and certainly to the same period that the positions in Sicily (Ziz (flower) / Palermo, Soeis (rock) / Solonte, Mortier (spinning) / Mozia ) to Kossura / Pantelleria and Malta.

8.Many testimonials attest, coins, dishes and even a statue of Hercules at Marsaxlokk discovery, near the Phoenician site of Tas-Silg. A Greek inscription of the sixth century BC. sheds light on the governance of the island. A democratic regime like the Greek cities existed in Malta with a Boule and a popular assembly, a great priest and two archons.

9.At the time of the Punic wars the archipelago is particularly disputed between Carthage and Rome. Some put as much zeal to defend the islands than others to conquer. On several occasions, they changde hands and were devastated each time. It is likely that the Maltese archipelago is an important link in trade with the current British Islands and Cape Verde, it has warehouses and merchandise, already, ship repair yards.

10.A prosecutor was established in Malta. Gozo and Malta later formed two municipalities and Roman laws were gradually introduced.

11.Liberal worship of the Romans is well known to historians and Malta will give an example. The site of the megalithic temple of Tas-Silg is proof. Dating phase Ggantija (3300-3000 BC.), this site will be used for more than four millennia up to the Arab occupation. The temple was a megalithic temple, a Punic temple to Astarte, a Roman temple dedicated to Hera / Juno and a Christian basilica. But it is the length of the Punic temple which suggests a long influence of the first Semitic colonization. Indeed, it is possible to have continued long after the beginning of the Roman occupation, the persistence of the temple to Astarte. The syncretism of Roman ended up playing, it is only during the first century BC. that it will be completely and permanently dedicated to Hera before being dedicated to Juno.

12.The location of the shipwreck of St. Paul in Malta. Other possibilities are considered: whether the proposed Meleda ( Mljet ) by P. Giurgiu in 1730 is not retained after completion of Ciantar, Maltese historian, as also that of Kefalonia, other options are acceptable including, among other Brindisi

13.In fact, the Christian religion in Malta is evidenced by the study of funerary complexes, that from the fourth century and is documented only from the sixth century

14.After the death of Muhammad in 632, the jihad will allow the expansion of Islam. First the Mashriq with the first three caliphs, the companions of the Prophet and the Maghreb and Al-Andalus with the Caliphs Umayyad. The Mediterranean is a “Muslim lake “for the Arab trade. The only challenge to its hegemony are the Byzantine emperors who, with Sicily and Malta, control the north bank of the passage between the eastern and western basin of the Mediterranean. The Aghlabids of Ifriqiya, in the early eighth century, to attack Constantinople where they fail despite a year of siege and Sicily, but they must give up to deal with revolts Berbers in North Africa ; finally the conquest of the island will not only ninth century and is particularly long (827-902).

15.The exact date of the decision of the Maltese Islands is debatable: 255 or 256 of the Hegira (868-8 December 20 December 9 December 869 or 869-28 November 870)

16.If the parallel is made with the occupation of Sicily or even al-Andalus, the Maltese population remaining should be divided between cabrd (slaves), muwalli (converted) and dhimmis (Christians free to practice their religion against payment of Taxes – jizya and Kharaj).

17.The Jews were expelled from Malta in 1492 by Ferdinand II of Aragon

18.The negotiations are tough, the Knights did not want to depend on no overlord. Charles V wanted each year a falcon from the Grand Master of the Order. To avoid excessive significance of this, the Grand Gaster will also offer oranges each year to the other Kings of the West.

19.composed mainly of farmers, sailors and craftsmen, some merchants and nobles

20.composed of Professor Themistocles Zammit, President of Honour, Guze Muscat Azzopardi, President, Pawlu Galea, vice president, Caruana Frangisk Saver, Secretary and Dun Karm Psaila, Ninu Cremona, Guze Demajo, Guze Micallef Goggi, and Vincenz Cachia Rogantini Misfud Bonnici, as members.

21.Wardija is the top of the hill on which Sciberras will be built the new Maltese capital of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Valletta, named after Jean Parisot de la Valette, Grand Master of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem who initiated its construction.

22.The rest of Malta’s oldest temple is a large dry stone wall built in the Neolithic Period on the site Skorba. Dating back to 5200 BC, it would be 700 years prior to the first megalithic building on the continent. 2400 years before the circle of Stonehenge (2800-1100 BC) and 2600 years before the pyramids of Egypt (2600 to 2400 BC).

Note by Joe Arevalo:

This work was discovered while searching for information on The Radio City Opera House, Hamrun, Malta. It’s author is unknown. This post was re-created in order to preserve the valuable information it contains.

10/10 dor

Fantastic website – passed on to family & friends