Stephen C Spiteri

Maltese ‘siege’ fortifications

The fortifications hastily erected by the Maltese insurgents were designed to keep the French garrison hemmed inside its fortified harbour enclave. Consequently, these fortifications were not really siege works in the true sense of the word.

The primary Maltese preoccupation throughout the revolt revolved around the fear of a punitive French reprisal against the rural villages. The inhabitants knew that they had neither the men nor the resources to lay siege to the formidable and well-armed harbour fortifications and so all their efforts were aimed at making a French excursion out of the harbour enclave as difficult as possible. Here, they ingeniously exploited the nature of the rural landscape surrounding the fortifications which, divided into innumerable stone-walled fields, provided a readymade system of entrenchments.

All that the inhabitants had to do was to link the field walls together, plugging in country lanes, roads, and valleys, and in so doing create an extensive and continuous form of circumvallation. They then stiffened this with a number of camps, batteries, and sentry-posts placed at strategic intervals. This organic form of circumvallation, laid out in a large crescent shaped line, spanned all the way from in front of Fort Tigné, to the west of the harbour entrance, right round to St. Rocco, opposite Fort Ricasoli on the other side of the anchorage – a perimeter of some 10 kms as the crow flies.

The insurgents’ main camps were situated at Gharghar, San Giuseppe, Tas-Samra, Corradino, Tarxien, Zejtun and Zabbar, with secondary camps to the rear at San Anton Palace in Balzan, and Città Vecchia.

Each camp was responsible for a number of batteries either in the vicinity of the camp itself, or spread out in the neighbouring countryside. Thus, for example, Vincenzo Borg’s men at Gharghar manned five such batteries, three large ones at Ta’ Ittwila, Imrabat, Ta’ Ischini and Sqaq Cappara, and Ghemmuna, all overlooking Fort Manoel and Tigne’, except for the last one. Other important batteries were located at Tas-Samra, facing Portes Des Bombes, Marsa (Jesuits Hill), Tarxien (Ta’ Borg), Corradino (della Campana and del Palazzo), Zejtun and San Rocco, facing the land front of Fort Ricasoli, and at Qala Lembi, opposite Fort Tigne’.

Most of the information regarding the insurgents’ defensive positions come from the so-called Lindenthal map.

Another plan seems to have been drawn up from surveys carried out by Captain Gordon and the Royal Engineers with soundings taken by Mr. Reynolds, Master in the Navy. The plan was copied by 2nd. Asst. Draughtsman Thomas Decklam, under the direction of Captain S. T. Dickens, CRE on 15 July 1803 (hereafter this plan is referred to as the ‘Gordon’ map).

Added to this cartographic information is the visual information provided by a number of contemporary drawings depicting a number of the batteries, mostly done by Antonio Grech which, despite their rather naive graphic style, provide valuable constructional details which otherwise would have been lost. All of these drawings, however, show the batteries from the rear and provide no information on the manner in which the faces of the batteries were revetted and strengthened against bombardment.

The available information tends to show that the locally-contrived fortified works were, basically, a cross between the coastal entrenchments of the Hospitaller period, most of which were erected post-1761, and improvised ‘opere soldatesche’ in stone. A close study of the available information on the Maltese siege fortifications shows that these consisted of three main types:

(a) large batteries of six to 9 guns placed behind masonry parapets, with flanking and rear walls surrounding a gun platform fitted, guncrew shelters, ‘barracks’ and sentry-post;

(b) small outlying batteries;

(c) long stretches of stone entrenchment walls for musketry fire.

The large batteries were in substance considerably more than just ephemeral fieldworks. It is not surprising that these works were modelled on the old coastal batteries and entrenchments built by the Knights (the last one of which was erected at Delimara Point in 1795) given that many of the capomastri and labourers involved in the construction of the siege batteries during the blockade would have had been continually employed in Hospitaller fortifications.

The most important and labour intensive part of these batteries was the main parapet, pierced with between four and six embrasures in the larger batteries. Contemporary watercolour paintings by Antonio Grech show the superior slopes of the batteries’ parapets and merlons, together with the roofs and terraces of adjoining magazines, as being covered with a thick layer of reddish soil. This was a technique intended to provide added protection to the masonry structures in order to prevent the stone from splintering on being hit by enemy shot – a technique which was also recommended earlier during the course of the eighteenth century by the Order’s French military engineers in one of their reports on the parapets of the harbour fortifications.

Judging from the scale of the drawings, this comprised a layer of soil some 30 cms thick spread out evenly on the superior slopes of the merlons and on the roofs of the adjoining sentry-post and buildings. It is not clear from the contemporary drawings if the superior slopes of the merlons were built with a pronounced slope or not, and if so, if these were covered in flagstones or lime-mortar in the established manner found in other Hospitaller fortifications.

Another important feature found in all the batteries, were the gun platforms. The contemporary drawings show that all embrasures and gun positions, including mortars, were equipped with hardstone flagstone platforms much in the same manner as can still be seen in many Hospitaller fortifications and batteries of the period.

Another important feature found in all the batteries, were the gun platforms. The contemporary drawings show that all embrasures and gun positions, including mortars, were equipped with hardstone flagstone platforms much in the same manner as can still be seen in many Hospitaller fortifications and batteries of the period.

Another important consideration in such large fieldworks would have been the need for the drainage of rain water. Again, no information is available on this issue, but without any such provisions, many of these batteries would have been turned into a morass of mud in the rainy seasons, and possibly also suffered structural instability in the enclosing walls and parapets. A number of camps and batteries were provided with a large underground barrel-vaulted magazine, or casemate, ‘magazeno sotteraneo coperto con troglio a’ prova di bomba’ capable of housing many soldiers.

The capomastri under the command of Vincenzo Borg ‘Brared’ built a five-gun position with an underground shelter within only a few days while another battery at Tal-Imrabat was fitted with two underground cellars capable of housing a hundred soldiers.

A feature common to most batteries seems to have been the small boxlike sentry rooms which could also have doubled up as a store for firearms and munitions. Vincenzo Borg is recorded to have built 25 such stone sentry rooms, many of which as freestanding posts along the surrounding country lanes and fields, in order to guard the line of circumvallation. This line of circumvallation was an interesting element that exploited an important characteristic feature of the Maltese rural landscape – the ubiquitous rubble-stone field walls.

A feature common to most batteries seems to have been the small boxlike sentry rooms which could also have doubled up as a store for firearms and munitions. Vincenzo Borg is recorded to have built 25 such stone sentry rooms, many of which as freestanding posts along the surrounding country lanes and fields, in order to guard the line of circumvallation. This line of circumvallation was an interesting element that exploited an important characteristic feature of the Maltese rural landscape – the ubiquitous rubble-stone field walls.

General Graham was much impressed by these walls. In a letter to the Duke of York, dated 30 December 1799, he wrote that ‘…the whole country is highly cultivated and divided into very small fields by dry-stone walls, frequently very high, which the barefooted inhabitants get over with great agility and behind which they are excellent tirailleurs. These walls everywhere go to the foot of the glacis, and around the Cottonera, which has none they run close to the works. Under their cover the Maltese frequently fire on the French sentries on the ramparts, showing great address in avoiding the return of musketry and grape-shot by shifting their places after firing; by those means they have made themselves very formidable to the French as marskmen. The enemy have no outposts nor do they show themselves outside their works.’

The defensive qualities of these field walls are best illustrated by the failed French counterattack of 12 September 1799, when a company of French soldiers from Fort Manoel undertook a sudden sortie to silence a solitary gun position posted on Mensija Hill (San Gwann). The French advanced up the hill close to the position but were stopped in their tracks with a hot hail of musketry fire from behind adjoining fieldwalls and trees and were soon forced to beat a hasty retreat once other insurgents from neighbouring positions began to congregate in the area and launched their own savage retaliatory attack.

Many buildings outside the established perimeter at times also served as ‘advanced’ posts. Casa Blacas, for example, abandoned after the summary murder of its owner, the Knight Vatanges, housed a company of soldiers from Tas-Samra camp, who were sent there to keep watch on San Giuseppe Road.

The work on all the fortified positions was usually done at night under the cover of darkness to prevent the French from firing on the insurgents as they thus employed. Many Maltese men, from all walks of life, gave a helping hand in their construction. John Camilleri, a priest, worked on the construction of Tal Borg Battery when not involved in the fighting. The men at countryside, thereby effectively sealing all approaches from Floriana.

The work on all the fortified positions was usually done at night under the cover of darkness to prevent the French from firing on the insurgents as they thus employed. Many Maltese men, from all walks of life, gave a helping hand in their construction. John Camilleri, a priest, worked on the construction of Tal Borg Battery when not involved in the fighting. The men at countryside, thereby effectively sealing all approaches from Floriana.

As an added anti-personnel measure, they also threw broken glass into the streets and country lanes. In a letter to Lord Hamilton dated 18 May 1800, General Graham, states that the whole area around the harbour, for a distance of eight miles, was littered with obstructions and the enemy only had a few roads which they could use to make a sortie. The roads in front of Fort Tigne’ and Fort Manoel, for example are described as being ‘very narrow and in a bad condition’ while all roads facing Cottonera and Fort Ricasoli had been ‘broken up or blocked’.

Vincenzo Borg had three large wooden beacons, enclosed in glass, built to alert vessels approaching Malta not to enter the Grand harbour. One of these was placed at St. Paul’s Bay (possibly on top of a tower), another at St. Julians and the third at Casal Zabbar in front of the Cottonera Lines. The men of Zejtun manned the towers and batteries of Marsaxlokk and Marsascala, and those of Mdina, St. Paul’s Bay.

(1) TAS-SAMRA BATTERY

Tas-Samra Battery was positioned on a hillock overlooking the Floriana land front fortifications and the main roadway out of Valletta and Floriana (through Porte des Bombes) along Strada San Giuseppe which passed through Hamrun and led north to Mdina. It also overlooked the sensitive areas down at Marsa and Corradino. It was known as an ‘advanced camp’ (‘campo avanzato della Samra’) given its proximity to the Floriana fortifications. Such was its importance, that the French, in a desperate attempt to neutralize it , had on one occasion bombarded it for five hours without respite. The Maltese, far from being discouraged, flew a large black flag from the battery and placed a large wooden cross on top of the nearby church. At one point it appears to have been armed with nine guns but is only shown with four guns and two mortars in a contemporary illustration. The battery platform had a broad v-shaped plan open at the rear but was shielded by a number of adjoining garden / fieldwalls, some buildings, and a church, all of which occupied the same hillock.

The battery parapet seems to have been fitted with five embrasures and a continuous flagstoned gunplatform.

Two small stone sentry boxes guarded the east side of the battery while a relatively large house and its walled garden enclosure protected the west flank of the battery. This building seems to have served as a sort of barrack for the troops for the drawing shows a flag flying from a pole fixed to the side of the building. The platform seems to have been bordered to the rear by a low masonry kerb.

The church of Our Lady of Atocia, (or Tas-Samra as it is known by the Maltese), with its arcaded portico stood immediately to the rear of the battery and is one of the few landmarks dating to the blockade that are still standing as existing at the time. The church contains one of the very last paintings by Antoine Favray, an altarpiece of the Virgin and Child signed and dated 1791. The contemporary drawing of the battery shows one of the side arches of the church’s portico. A large sundial is carved into the masonry on the south side of the church. Another large building, still standing, stood a little distance away in an alley to the rear of the church. This too given its size and dominating position could have been used to accommodate the 223 men stationed in the Tas-Samra camp.

Other documents state that it was at times garrisoned by as much as 600 men owing to its very close proximity to the Floriana outerworks and fortifications.

According to Mifsud, the Samra camp was garrisoned by the battalions of Zebbug, Siggiewi, and Naxxar and, later, was also assisted by English sailors and marines. The Zebbug battalion was divided into four companies and each in turn into three platoons. A half ‘guard platoon’ consisting of a sergeant, corporal and twelve soldiers, kept constant watch on top of the Atocia Church. Another platoon was stationed on the ‘ramp’ of the camp.

The Tas-Samra camp was under the overall command of Canon Frangisku Saverio Caruana and the direct command of Angelo Cilia and his deputy Isidoro Attard. It had a chaplain, Fra Antonio Baldacchino, and a surgeon, Antonio Muscat. Vincenzo Borg states that two of the guns, possibly the 32-pdr culverines, were brought from B’kara after having been removed and transported with great difficulty from St. Mary Tower in Comino.

Tas-Samra camp fed two other small batteries located in the immediate vicinity. One, a four gun emplacement, was placed some distance down the hill in front of Casa Blacas (marked ‘A’ on map), itself used as a blockhouse. The other, smaller, was armed with three cannon and surrounded by a moat filled with water.

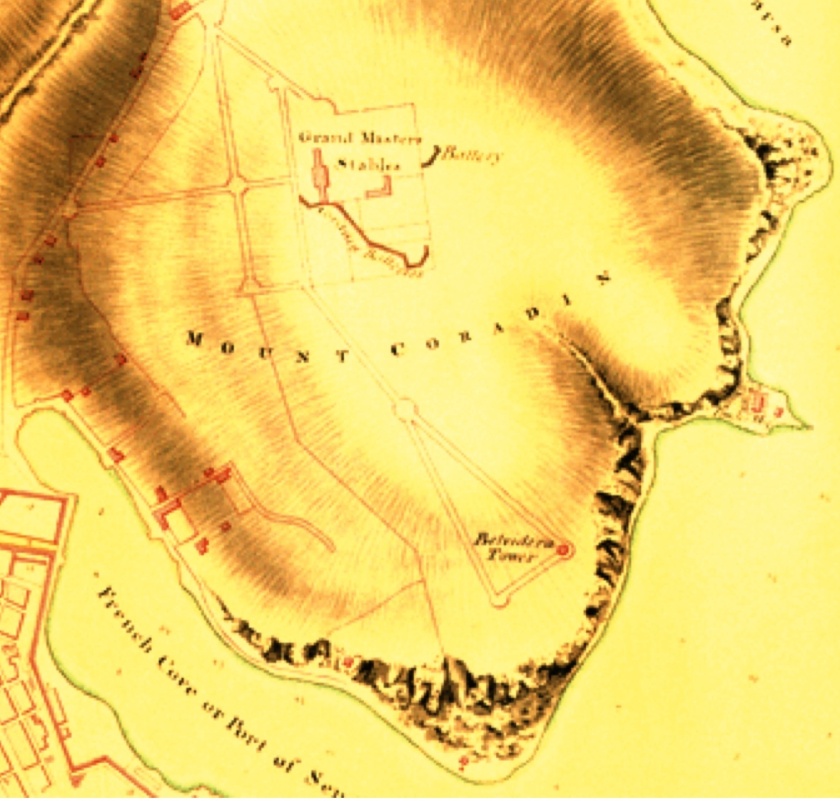

(2) CORRADINO BATTERIES

The Corradino camp and batteries covered a very large surface area and presented one of the largest advanced positions held by the insurgents. The battery and camp were sited on, and exploited, the extensive grounds and fields of the what had been the Grand Master’s Stables.

This large, and little known building, a Baroque palace-like structure, is shown in a painting of Corradino and was a very distinctive landmark. It was eventually demolished by an order of 21 January 1811, when, because of its old and ruinous state (possibly because of the French bombardment) it was dismantled and its stonework reutilised for the formation of a new coastal road at the foot of the Corradino headland. It was a massive building which must have also served as a barracks for the insurgents. Santo Formosa was seriously wounded in his right leg when the building was hit by a French bomb which crashed through three floors, burying him in the debris.

The Corradino position consisted of three batteries: one covering the main entrance to the stables and facing Ghajn Dwieli (A); another linked by a long entrenchment wall, overlooking the Grand Harbour (B); and a third, isolated, situated towards the south western end of the enclosure, overlooking the Floriana Lines (C). Mifsud states that the position was divided into two parts. The first was an entrenchment known as Della Campana which overlooked the road coming from Senglea. This was armed with two 8-pdr cannon removed from the Xrop (Xiorb) l-Ghagin coastal entrenchment. The second consisted of two batteries, one of which he calls ‘la trincea del palazzo’ (i.e. the Grand Master’s stables) which was armed with two 8-pdr guns placed in front of the entrance to the palace, facing Ghajn Dwieli, and the other, also with two pieces ‘dietro il palazzo’, facing Marsa, as shown in the Gordon map.

Early in the insurrection, Santo Formosa armed the position with four 6-pdr guns while the British later added two 9-inch mortars and a third. North of the position, towards the cliff-face of the Corradino heights, stood a ‘Belvedere Tower’ which may also have been used as an advanced sentry post by the insurgents.

No contemporary drawings of Corradino batteries are known. The Lindenthal and Gordon maps differ on the plan of this battery. The graphic reconstruction shown here is based on the more detailed Gordon map. A coloured sketch by Agostino Scolaro, entitled ‘Sortita de’ francesi nel Coradino nel 1798′ shows French troops attacking the position, from the main road at Ghajn Dwieli, with the ‘palazzo’ to the rear, and the Maltese insurgents firing back from behind the safety of the field walls in the area.

The whole position is recorded as having been armed with five cannon, amongst these an 18-pdr taken from St Julian’s Battery.

The Corradino camp was garrisoned by 224 men, mostly from Rabat and Casal Dingli and placed under the overall command of Emmanuele Vitale.

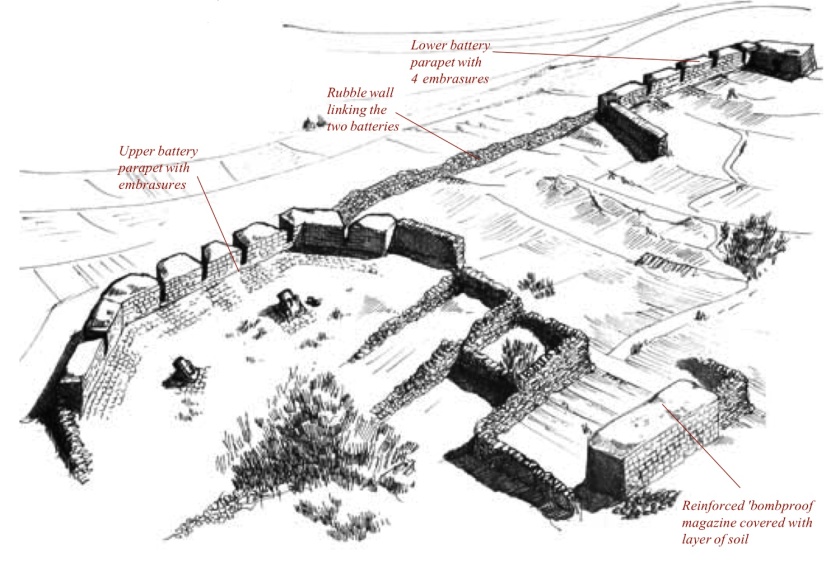

(3) TAL-BORG BATTERY – TARXIEN

Tal-Borg Battery was located on high ground, north of the village of Tarxien and about 700m south of St. John Almoner Bastion on the Cottonera enceinte. It was one of the largest and best defended batteries erected by the Maltese insurgents during the course of the blockade.

It was built in a field belonging to a certain Caterina Busuttil who later received 142 scudi in compensation. According to the Gordon map, the work consisted of a large platform, built on two different levels, apparently at different stages. Grech’s drawing shows a thick masonry parapet, seven courses high protected with a covering layer of soil on the superior slopes of the merlons.

The west side of this battery, facing Corradino, was flanked by a large partially ruined rectangular farm building (‘razzett’) which was incorporated into the layout to serve both as a traverse and a protective shelter for the gun crews and garrison.

Contemporary drawings also show a large barrack building, with its roof well covered in a protective layer of soil and with a side entrance facing away from the line of enemy fire, towards the rear of the gun platform.

Unlike the other works, the Tal-Borg Battery was defended to the rear by a entrenchment-like wall stiffened at the salient with a small bastion, in the manner encountered at the Ta’ Falca entrenchments near Mgarr, built by the Knights around 1732. The Lindenthal and Gordon maps differ in the plan and details of the battery. The plan shown in the Gordon map, however, corresponds more closely to the illustration by Antonio Grech.

This battery is known to have been built under the able supervision of the engineer Michele Cachia. The position was garrisoned by a company of around 230 men.

The main upper platform, and the first to be built, was armed with five iron cannon ‘fatti nella fabrica di S. Gervas e portati dalla Cottonera’, together with two 6-inch mortars disembarked from a British vessel on 7 December 1798. Grech’s drawing also shows a naval carronade placed on a static naval mount.

The lower battery was armed with only two guns but seems to have had at least five embrasures. Mifsud states that the Tal-Borg Battery was later armed with two ‘fusieri che sparano colle granate’ as well as nine 18-pdrs, four of which ‘vennero posti sotto la batteria Tal Borg in un’altra batteria’. At least one of the guns, as shown in Grech’s drawing (and perhaps even more) was employed in protecting the rear of battery, its muzzle opening out through a cutting in the rubble, field wall type of entrenchment placed across the gorge of the work. The enclosure, however, was only loosely formed and had a crude cutting in lieu of a gateway. At least one internal field wall, probably retained from an existing field, seems to have served as a traverse, dividing the interior into areas. The Grech drawing also shows two small box-like sentry rooms grafted onto the main parapet, both of which were fitted with flagpoles and shown flying the colours of the Kingdom of Two Sicilies and the Royal Navy respectively.

Grech’s illustration also clearly shows an open well (bir) situated close to the flanking building on the western end of the battery, immediately to the rear of the gun-platform. It also hints at the existence of a third parapet, fitted with embrasures, grafted to the left of the farm building.

No traces of the battery exist nowadays but it is said that Tal-Borg Battery occupied the site of the present-day Pace Grasso football ground.

(4) CAPUCHIN CONVENT BATTERY

The Capuchin Convent Battery was a medium sized gun position facing Kalkara Creek and the Post of Castile in Birgu.

It was very close to the Cottonera fortifications but sheltered from them by the Capuchin Convent on its left side. It was built in such a manner to cut across and plug a country lane (today Triq il- Kapuccini) coming up from Kalkara Creek. The convent itself (albeit reshaped) and the country lane still exist.

There is no reference to this battery or its armament other than in the Gordon map. It may have been one of the batteries built by Captain Ball in the vicinity of Bighi which he mentions in a letter to Lord Nelson.

(5) ST. PETER BATTERY & THE ZEJTUN BATTERIES

Like the Capuchin Battery, there is hardly any record of St Peter’s Battery other than the entry in the Gordon map.

This small battery was situated some three hundred metres to the rear of the Capuchin Battery, roughly half way between the latter and St Rocco Chapel. It was probably manned by the Zejtun militia. Its armament is unknown.

The village of Zejtun, which is not shown in the Gordon map, had a number of small batteries. One, called ‘della Croce’, was situated close to the parish church. Another two, known as ‘Tal Caspio’ were situated close to St. Clement’s Church and were armed with two 8-pdrs. Another three, known as ‘Tal Fax’, were placed close to the Church of St. Gregory guarding the road to the bay of Marsascala. The proposed reconstruction of the battery shown below is purely hypothetical in its details, and is based on the elements found in the other documented batteries. The Gordon map shows an open work to the rear and was fronted by an ascending road. There seem to have been no farm buildings in the vicinity for quite some distance all around, thereby suggesting that some form of barrack accommodation could have been provide by an underground vaulted chamber as built at the Gharghar Battery.

(6) WINDMILL REDOUBT

Windmill Redoubt was situated along the line of circumvallation linking the towns of Zabbar and Tarxien and guarding the road to Zejtun.

The windmill itself, with some modifications, is still standing while the immediate area around it now serves as a large traffic round about.

The redoubt, constructed of rubble-stone walls, possibly incorporating stretches of existing field walls, was roughly triangular in plan and was designed in such a way as to plug three intersecting country lanes, the present day Triq 10 ta’ Settembru 1797, Triq id- Dejma, and Triq Ghollieq.

The solid windmill building, which occupied nearly all the north side of the redoubt, served as a blockhouse, providing accommodation and shelter to the troops assigned to defend it, while its tower doubled up as an excellent lookout post from where Maltese insurgents kept a watch on neighbouring enemy positions and the gateways along the Cottonera enceinte.

No information is known as to the size of the garrison and number and quality of cannon and other armaments that were deployed in this post.

(7) ZABBAR BATTERIES & REDOUBT

Zabbar, or Citta’ Hompesch as it was called in the last years of the Order’s rule, was the closest Maltese town to the French harbour fortifications.

As such, it received continual French attention, being repeated attacked by French troops and bombarded from the guns on the Cottonera ramparts. The people of Zabbar reacted by barricading its streets and alleys and fortified it with batteries and a redoubt.

Mifsud mentions that the villagers erected a battery ‘sotto la statua della Madonna con 2 pezzi di artiglieria’ and built two other trincee in the square near the church of St. Roque and in the ‘piazza che da per la strada detta Ta’ Uied il Ghajn (Wied il-Ghajn). The Gordon map shows three batteries, altogether plugging the main approaches to the main town square and church, together with a large reboubt. The latter consisted of a large tenaille-trace type of entrenchment built to envelope a large building, or block of houses, fronting a road leading into the town, present-day Triq Bajada.

This redoubt is very similar in plan to the ‘pietra a secco’ type of entrenchment which was built by the knights around the base of St. Agatha Tower in Mellieha.

The Zabbar militia battalion was under the command of Clemente Ellul, and his deputies Giuseppe Cachia and Giuseppe Ellul. The artillery men at Zabbar were Francesco Grima, Giuseppe Bonnici, Francesco Pace, Pasquale Falzon, Giovanni Spiteri, Salvatore Micallef, Paolo Scicluna, Michele Darmanin, Giuseppe Agius and Angelo Fava.

In a letter to Lord Hamilton (18 May 1800), General Graham states that the batteries near Zabbar were completely protected by stone casemates, thereby suggesting that these positions were either fitted with underground shelters for the troops, as at Gharghar, or were covered over to protect the gun crews.

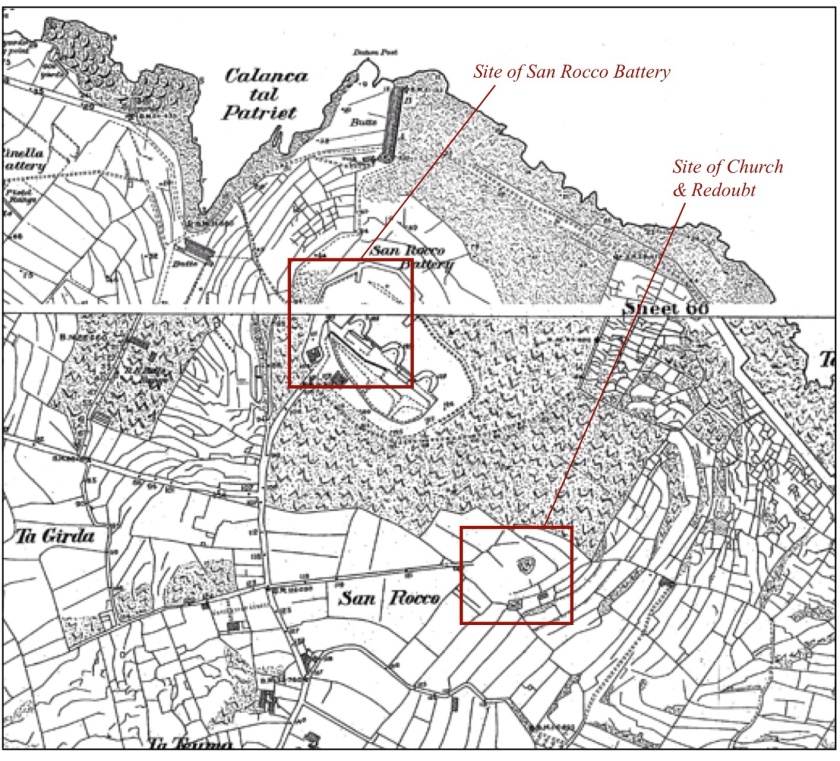

(8) SAN ROCCO BATTERY

The San Rocco, or St. Rocque Battery marked the southernmost end of the Cottonera side of the insurgents’ circumvallation.

This position was set up to control both Fort Ricasoli and the entrance to the Grand Harbour.

The battery consisted of two distinct gun platforms set on top of a low hillock (later occupied by Fort St. Rocco – 1872), and at a distance of around 30-50 ms apart, open to the rear and separated by a various field / orchard walls. The position was served by a large magazine built by Michele Cachia around December 1799, in which were employed timber beams removed from the ‘Casini di Casal Nuovi’ (Rahal il-Gdid).

Initially the work was armed with only two 6-pdr iron guns but as can be seen from a contemporary drawing the two positions were armed with a total of 10 guns and two mortars by the end of the blockade. The main battery, situated on higher ground contained most of the guns. Mifsud states that the ‘gran trincea detta di San Rocco’ was armed with a total of seven guns, five 12-pdr cannon and two 8-pdrs. The lower battery, however, situated closer to the shoreline, is shown armed with four guns. Possibly these are the four 32-pdrs listed in Mifsud’s table which would have been most usefully employed in a coastal defence role, aimed at mouth of the harbour.

The Gordon map shows two batteries fronted by a country lane straddling a hillock, south of which stood a long stretch of rubble-stone type of coastal entrenchment built by Bali de’ Tigne in the latter half of the eighteenth century.

Gen. Graham was not much impressed by San Rocco Battery. He remarks that it was continually being fired upon by the French gunners in Fort Ricasoli even though it was about 700m distant from the fort.

(9) JESUIT HILL BATTERY

The batteries overlooking the inner reaches of the Grand Harbour, in the area generally known as Marsa are well documented. The one occupying the higher ground, known as Jesuit Hill ( Jesuit Battery or Point Cortin Battery), was aimed at the harbour side of the Floriana enceinte. This small battery was considered as an advanced post of Tas-Samra camp although its guards came from Casal Fornaro (Qormi).

Grech’s drawing shows a small battery armed with only two cannon, fronted by a short stretch of masonry parapet pierced with two embrasures, a flanking rubble wall (possibly an existing field wall) on one side, and a large magazine expertly grafted into the adjoining terracing on the other. In this manner the magazine was well camouflaged and protected by a thick layer of soil.

Grech’s drawing, as well as the Gordon map, show a large building situated to the rear of the battery. This could have served as a kind of blockhouse or barrack block. In Grech’s drawing, one of the corners of this building is shown being hit by a cannon ball fired from a French battery on Magazine Bastion at Floriana – the insurgents guns are returning fire.

(10) MARSA BATTERY

The second battery in the inner harbour area was Marsa Battery, or ‘Trincea della Marsa’ which was situated at the foot of Jesuit Hill, close to the shoreline. This was also a small work consisting of a short parapet fitted with three embrasures, the merlons being of unequal length, and served by a continuous hardstone platform.

Contemporary drawings show a sentry room or magazine to the left and a low rubble stone type of flanking wall to the right. It was armed with two iron guns and a howitzer on a field carriage. An often published drawing shows Captain Alexander Ball and Gen. Graham inspecting the Marsa Battery on horseback. The same howitzer is again shown in the background.

Salvatore Camilleri from Valletta claimed that he had made the ‘modello’ of this battery and even built at his own expense the ‘casamatta’ or magazine which seems to have been located immediately to the rear of the work. Unlike the other batteries, the superior slopes of the merlons of the Marsa Battery are not shown covered with a protective layer of soil.

(11) GHARGHAR BATTERY

The Gharghar, or Harhar (Araar), Battery, also known as Ta’ Ittuila (It-Twila) was one of the batteries built by Vincenzo Borg. It was designed to control the approaches from Gzira and overlooked the land front defences of Fort Manoel. The Gharghar Battery is beautifully illustrated in one of Grech’s drawings which shows a relatively linear platform with a high frontal masonry parapet, two flanking walls, the right one of which is clearly built onto an existing fieldwall, and encloseing the rear, a high rubble wall which stopped short of the flanking walls to provided entrances into the work.

The drawing shows three masonry sentry posts, one on either side of the gun platform and a third guarding the opening at the rear of the battery. Presumably, a fourth would have protected the left opening (not shown in the picture).

Gharghar Battery was fitted with an interesting arrangement for the accommodation of troops in the form of an underground vaulted casemate, a ‘magazeno sotteraneo copertro con troglio a prova di bomba’ capable of housing a hundred men, although this claim may be slightly exaggerated given the scale of the structure. The Grech drawing shows a semi-circular double arched barrel-vault, what at the time would have been termed ‘troglio raddopiato’ and covered with soil. A second anonymous drawing of the battery shows a rectangular opening in the ground, at the rear of the gun platform, possibly a ventilation shaft feeding the underground casemate. It is not clear, however, if this drawing actually depicts the Gharghar Battery and not another smaller battery situated in the vicinity, as clearly shown in the Lindenthal map. This is because the second drawing shows a parapet with only five embrasures and no sentry rooms along the flanks.

The Grech’s drawing, however, depicts a parapet pierced by six embrasures, the merlons of which are covered with a protective layer of soil. The battery was armed with ‘cinque pezzi di cannone da 18′ (18- pdrs, with each gun served by its own wedge-shaped platform as shown in the diagram below. Some of the guns used to arm this battery were transported all the way from the Hospitaller coastal battery at Mistra. General Graham’s report on the posts, number of men and ordnance drawn up on 28 December 1799 shows the Gharghar or B’kara camp armed with a total of eight 18- pdr guns. However, this is a collective figure which also incorporates all the other batteries and advanced positions erected by Salvatore Borg in the vicinity of Fort Tigne’ and Sliema.

The Gharghar Battery is shown fitted with two flagpoles flying British colours and those of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Mifsud states that it was in this battery ‘ove fu’ inalberato lo Stendardo Inglese per la prima volta nella Campagna di Malta’.

The Gordon map shows the battery situated high on a hill flanked by two valleys and isolated from any neighbouring farm buildings. There were also no roads or country lanes leading to the position. Various advanced posts surrounded the position. Amongst these was a solitary gun emplacement at a locality known as ‘Il-Harrub ta’ Stiefnu’ which had been set up since the first days of the insurrection. Early twentieth century survey sheets of the Gharghar site show a chapel which is still standing. This would have been located to the rear of the battery, while a farm building which was occupied by Vincenzo Borg’s men, served as his field headquarters.

The Gharghar camp was garrisoned by the men of the B’kara and Mosta Battalions. General Graham’s report of 28 December 1799, cited earlier, gives the total number of men stationed at the Gharghar camp as 338. It was estimated that a soldier stationed at the Harhar camp cost the Maltese authorities around two tari and ten grani a day. An interesting detail in Grech’s depiction of Gharghar Battery is provided by the small herd of the cattle shown grazing in the fields adjoining the position.

(12) SLIEMA BATTERIES

Vincenzo Borg was, undoubtedly, the most successful builder of Maltese fortifications during the blockade. His works stretched from the limits of Tarxien all the way to Sliema. Mifsud states that Borg was responsible for building at least four other batteries on the Marsamxett side, apart from the central Gharghar Battery.

These comprised a battery known as Ta’ Imrabat (possibly in the vicinity of present-day Imrabat Street) which was built to take four ‘mortari di bomba’ and fitted with a large bombproof, underground vaulted casemate (‘magazeno sotteraneo a prova di bomba’) capable of housing, like the Gharghar Battery, a 100 men, as well as a guncrew shelter capable of accommodating ‘circa vent’artiglieri’ (marked ‘C’ on sketch plan).

The second, called Ta’ Ischina’ was a small work equipped with an 18- pdr situated in a field called Ta’ Xini ( Ta’ Cini). Vincenzo Borg used to spend many a night on guard duty at this post on the look out for French vessels attempting to leave the harbour.

A third battery, called Ta’ Sqaq Cappara (present day Kappara), was built closer to Fort Manoel which it was intended to bombard. It is shown in the Lindenthal map, sited below and to the north of the Gharghar Battery. Surprisingly it is omitted from the Gordon map. This may also be the battery depicted in the anonymous drawing often taken to represent the Gharghar Battery.

The Gordon map shows in great detail the location of a large number of batteries and parapets situated along a road descending from a hillock at Sliema and ending at a coastal battery facing Fort Tigne’.

In all, the Gordon map shows six different walled positions situated along the present day Triq il-Kbira. One of these batteries was sited exactly opposite the facade of the small church of Our Lady of Divine Grace. One of these, at Ghar il-Lembi (possibly the one marked ‘A’) was armed with three guns, to be followed by a second (B) armed with two iron guns closer to the enemy.

The Gordon map also shows that the end of the insurgents line was marked by a coastal battery situated at what appears to be Font Ghadir, slightly to the rear of the small headland later the site of Fort Sliema (1872). This may be the Ta’ Ischina Battery mentioned earlier. If not, then no information exists to date on this obscure work.

Carmelo Testa wrote that Vincenzo Borg was also responsible for building a large coastal work at Dragonara point, in front of the Spinola entrenchments, the site of the present-day Casino. This battery was known as Ta’ Ghemmuna and contained an extensive parapet fitted with nine embrasures and a large magazine. It was built in February 1799 after news reached Malta that a strong French naval force with some thirty vessel was sighted approaching the Island and the British blockading ships had to leave Malta to regroup under Nelson leaving the island unprotected. This battery, which was armed with seven guns, was intended to prevent the French from landing troops at St. George’s and St. Julian’s bays and thereby attack the insurgents positions from the rear.

ST. LUCIAN ENTRENCHMENT AND REDOUBT

The greatest fear of the British military force in Malta in 1799 was the threat posed by the possibility of the arrival of large French relief force, in the event of which, British troops would have had to be evacuated.

An emergency retreat and evacuation plan was therefore laid down to ensure an organized and quick retreat from the Island from the harbour at Marsaxlokk. This involved the construction of a strong redoubt around St. Rocco Chapel, halfway between the village of Zabbar and the coast, in the vicinity of the old Hospitaller Tower at Delle Grazie (today Xghajra). This work was intended to shield the retreat of British troops from San Rocco Battery towards Zabbar. This town was to serve as rallying point for all the British forces and from there they where to be pull back hastily to the village of Zejtun.

Once at Zejtun, the British regiments (30th and 89th) were to retreat to the safety of ships waiting at anchor near St. Lucian’s Tower (or Fort Rohan as it was called after its was enclosed, together with its battery, by a ditch in the 1790s) in Marsaxlokk Bay.

This formidable Hospitaller tower with its adjoining battery was to serve as the keep of a large British entrenchment cutting off the neck of the St. Lucian peninsula. Here the British military, assisted by the Maltese engineer Matteo Bonavia, established an extensive defensive perimeter, a continuous wall which, as shown in Lindenthal’s map, sought to seal off the peninsula from the rest of the mainland (see aerial photograph). The position was strengthened further with the construction of a diamond-shaped redoubt built on the ahead of the entrenchment. The Gordon map does not included the fortifications erected around St. Lucian but it does show the layout of the redoubt built at St. Rocco, which incorporated into its enclosure a small rural chapel and an abutting building. None of these works have survived.

In December 1799, Gen. Graham wrote to the Duke of York to inform him that the strong ‘moat’ [sic – entrenchment] which he was constructing ‘about a mile-and-a-half behind the ridge of Gudja and Zejtun to serve as a place of retreat and communication with the ships and stores’ was ‘nearly completed and being supported by some of the high towers on the coast’. Graham was confident that this work was capable of providing adequate protection ‘for some days’ if attacked.

Wow, what a wonderful site, I visited Malta for the first time last year (a week in Valletta and a week on Gozo) and fell in love with the island I can’t wait to return. It is just one fascinating huge open air museum, my next visit will be much more informed with thanks to your blog.

Thank you for your kind words. I really hope you will visit our beautiful islands again. Enjoy your stays in Malta & Gozo

Very interesting.

I am always looking forward for some new documented history of Malta. As I was employed with the British Services. To be exact REME.

I had access to all the defence locations, being a technicion on firing control equipment. Three items that may be not known,could be:

1st – Fort Madaliena’s one of the guns was fired by mistake in the 50’s,

2nd – Benaghjsa was used to test the Getman V1 rocket prior to making the ground to air missiles.

3rd – Fort Rocco were installed 5.25 inch dual action guns, just before the Suez crisis

Very interesting website, well done. I’ve spent lots of evenings browsing and really enjoyed everything. Do you have any information about whether any of these batteries, redoubts, or entrenchments still can be fully or partially seen other than the info provided on this page? Thanks!

All French Blockade Batteries are now non existant

very interesed indeed