Malta has often been called the ‘Fortress Island’ due to the great mass of military architecture that can be seen everywhere. This is a legacy of the islands’ history which saw them being fought over, time and again, due to their strategic location and deep, safe harbours.

The fortifications that can be seen today come from two distinct periods: those of the Knights and those of the British era. These imposing reminders of the islands’ wartime past fascinate not only because they are a feat of military engineering, but also because they are reminiscent of an age of chivalry, crusading, heroism and legendary battles.

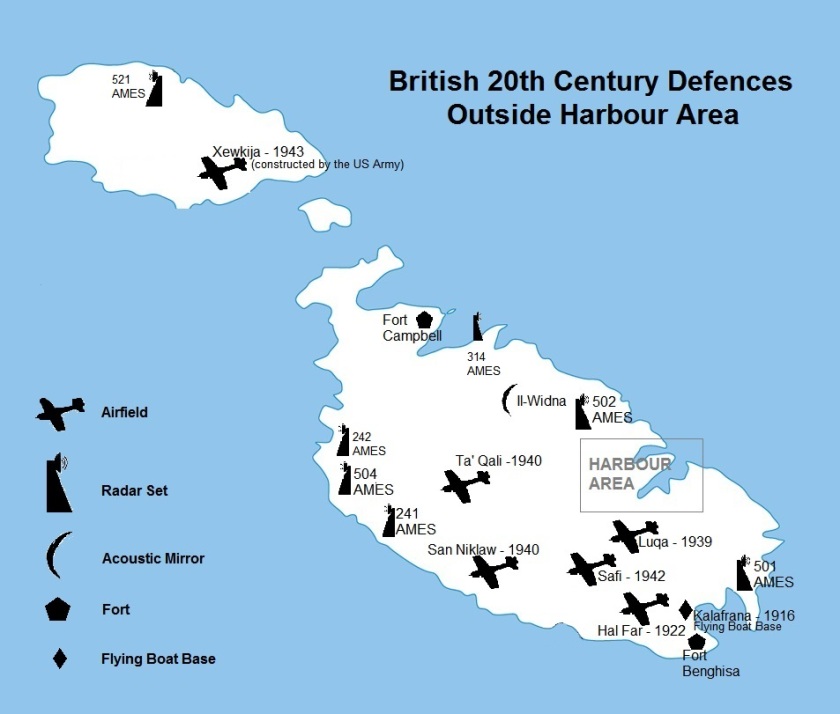

Wherever you go in Malta you will find remnants of war, from 17th century coastal forts and watch towers to WWII pillboxes.

ORDER OF ST JOHN PERIOD

Some Fortifications and Batteries

Fort St Angelo

Fort St Angelo is a large fortification in Birgu, right at the centre of Grand Harbour.

History

Medieval Times

The date of its original construction is unknown. However, there are claims of prehistoric or classical buildings near the site, due to some large ashlar blocks and an Egyptian pink granite column at the top part of the fort. There is also the mentioning in Roman texts of a temple dedicated to Juno/Astarte, probably in the vicinity of the fort. There is also the popular attribute to its foundation to the Arabs, c. 870 AD, but nothing is concrete although al-Himyarī mentions that the Arabs dismantled a hisn (fortress), but there is no actual reference if this ‘fortress’ was in Vittoriosa. It probably started as a fortification in the high/late medieval period. In fact, in 1220 Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick II started to appoint his own Castellani for Malta who needed a place to live and secure the interests of the crown. The remains of a tower that may date back to the 12th century can be traced among the more recent works. The first mention of Castrum Maris (“Castle by the sea”) is to be found in documents from the 1240s when Paulinus of Malta was the Lord of the island and later when Giliberto Abate made a census of the islands. Another reference to the castle is from the short Angevin rule (1266–83) where documents list it again as Castrum Maris and list a garrison of 150 men together with several weapons. It seems also that by 1274 the castle already had two chapels which are still there today. From the same year exists also a detailed inventory of weapons and supplies in the castle. From 1283 the Maltese islands were under Aragonese rule (although the castle withstood for some time in Angevin rule while the rest of Malta was already in Aragonese hands) and the fortification was mainly used by Castellani (like the de Nava family) who were there to safeguard the interests of the Aragonese crown. In fact the Castellans did not have any jurisdiction outside the ditch of the fort.

The date of its original construction is unknown. However, there are claims of prehistoric or classical buildings near the site, due to some large ashlar blocks and an Egyptian pink granite column at the top part of the fort. There is also the mentioning in Roman texts of a temple dedicated to Juno/Astarte, probably in the vicinity of the fort. There is also the popular attribute to its foundation to the Arabs, c. 870 AD, but nothing is concrete although al-Himyarī mentions that the Arabs dismantled a hisn (fortress), but there is no actual reference if this ‘fortress’ was in Vittoriosa. It probably started as a fortification in the high/late medieval period. In fact, in 1220 Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick II started to appoint his own Castellani for Malta who needed a place to live and secure the interests of the crown. The remains of a tower that may date back to the 12th century can be traced among the more recent works. The first mention of Castrum Maris (“Castle by the sea”) is to be found in documents from the 1240s when Paulinus of Malta was the Lord of the island and later when Giliberto Abate made a census of the islands. Another reference to the castle is from the short Angevin rule (1266–83) where documents list it again as Castrum Maris and list a garrison of 150 men together with several weapons. It seems also that by 1274 the castle already had two chapels which are still there today. From the same year exists also a detailed inventory of weapons and supplies in the castle. From 1283 the Maltese islands were under Aragonese rule (although the castle withstood for some time in Angevin rule while the rest of Malta was already in Aragonese hands) and the fortification was mainly used by Castellani (like the de Nava family) who were there to safeguard the interests of the Aragonese crown. In fact the Castellans did not have any jurisdiction outside the ditch of the fort.

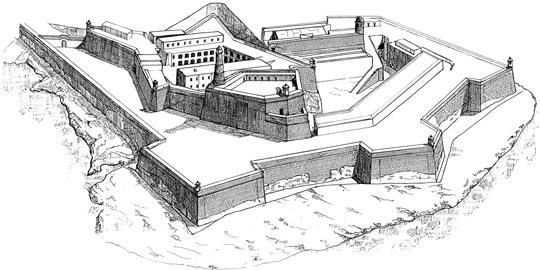

Knights’ Period

When the Knights of St John arrived in Malta in 1530, they chose to settle in Birgu and Fort St Angelo became the seat of the Grand Master, which included the refurbishing of the Castellan’s House and St. Anne’s Chapel. The Knights made this their primary fortification and substantially reinforced and remodelled it, including the cutting of the dry ditch to make it a moat and the D’Homedes Bastion built by 1536. By 1547, a large cavalier designed by Ferramolino was built behind the D’Homedes bastion and also the construction of the De Guirial battery right at the tip of the fort by sea level to protect the entrance to Dockyard Creek. These works transformed the fort into a gunpowder fortification. Fort St Angelo withstood the Turks during the Great Siege of Malta during which it succeeded to withstand a sea attack by the Turks on Senglea on 15 August 1565. In the aftermath of that siege the Knights built the fortified city of Valletta on Mount Sciberras on the other side of the Grand Harbour and the administrative centre for the knights moved there. It was not until the 1690s that the fort again underwent major repairs. Today’s layout of the fort is attributed to these works which were designed by Carlos de Grunenburgh, who also paid for the construction of four gun batteries on the side of the fort facing the entrance to Grand Harbour. As a result, one can still see his coat of arms above the main gate of the fort. By the arrival of the French in 1798, therefore, the fort became a very powerful fortification including some 80 guns, 48 of which pointed towards the entrance of the port. During the short two-year period of French occupation, the Fort served as headquarters of the French Army.

When the Knights of St John arrived in Malta in 1530, they chose to settle in Birgu and Fort St Angelo became the seat of the Grand Master, which included the refurbishing of the Castellan’s House and St. Anne’s Chapel. The Knights made this their primary fortification and substantially reinforced and remodelled it, including the cutting of the dry ditch to make it a moat and the D’Homedes Bastion built by 1536. By 1547, a large cavalier designed by Ferramolino was built behind the D’Homedes bastion and also the construction of the De Guirial battery right at the tip of the fort by sea level to protect the entrance to Dockyard Creek. These works transformed the fort into a gunpowder fortification. Fort St Angelo withstood the Turks during the Great Siege of Malta during which it succeeded to withstand a sea attack by the Turks on Senglea on 15 August 1565. In the aftermath of that siege the Knights built the fortified city of Valletta on Mount Sciberras on the other side of the Grand Harbour and the administrative centre for the knights moved there. It was not until the 1690s that the fort again underwent major repairs. Today’s layout of the fort is attributed to these works which were designed by Carlos de Grunenburgh, who also paid for the construction of four gun batteries on the side of the fort facing the entrance to Grand Harbour. As a result, one can still see his coat of arms above the main gate of the fort. By the arrival of the French in 1798, therefore, the fort became a very powerful fortification including some 80 guns, 48 of which pointed towards the entrance of the port. During the short two-year period of French occupation, the Fort served as headquarters of the French Army.

The British Period

With the coming of the British to Malta the fort retained its importance as a military installation, first in use by the Army. In fact, in 1800, two battalions of the 35th Regiment were resident in the fort. However, at the start of the 20th century, the fort was taken over by the Navy and it was listed as a ship, originally in 1912 as HMS Egremont, when it became a base for the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, but in 1933 renamed as HMS St Angelo. The British did not make many modifications to the fort, although they built a casemated battery for three nine-inch RML guns in the 19th century and also a cinema and a water distillation plant in the early 20th century. During World War II, the fort again stood for siege with an armament of 3 Bofors guns (manned by the Royal Marines and later by the Royal Malta Artillery). In total, the fort suffered 69 direct hits between 1940 and 1943. When the Royal Navy left Malta in 1979 the Fort was handed to the Maltese government and since then parts of the Fort have fallen into a state of disrepair, mostly after a project to transform it into a hotel during the 1980s.

With the coming of the British to Malta the fort retained its importance as a military installation, first in use by the Army. In fact, in 1800, two battalions of the 35th Regiment were resident in the fort. However, at the start of the 20th century, the fort was taken over by the Navy and it was listed as a ship, originally in 1912 as HMS Egremont, when it became a base for the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, but in 1933 renamed as HMS St Angelo. The British did not make many modifications to the fort, although they built a casemated battery for three nine-inch RML guns in the 19th century and also a cinema and a water distillation plant in the early 20th century. During World War II, the fort again stood for siege with an armament of 3 Bofors guns (manned by the Royal Marines and later by the Royal Malta Artillery). In total, the fort suffered 69 direct hits between 1940 and 1943. When the Royal Navy left Malta in 1979 the Fort was handed to the Maltese government and since then parts of the Fort have fallen into a state of disrepair, mostly after a project to transform it into a hotel during the 1980s.

Present and future

Use of the fort has been granted to the Order of Malta. Other parts are leased to the Cottonera Waterfront Group, a private consortium. On 5 March 2012, the government of Malta announced that the European Regional Development Fund is to allocate €13.4 million for the restoration of the fort. The restoration is being managed by Heritage Malta.

Fort St Elmo

Fort Saint Elmo is a fortification in Valletta. It stands on the seaward shore of the Sciberras Peninsula that divides Marsamxett Harbour from Grand Harbour, and commands the entrances to both harbours.

Fort Saint Elmo is a fortification in Valletta. It stands on the seaward shore of the Sciberras Peninsula that divides Marsamxett Harbour from Grand Harbour, and commands the entrances to both harbours.

History

Prior to the arrival of the Knights of Malta in 1530, a watchtower existed on this point. Reinforcement of this strategic site commenced in 1533.

When the Knights of the Order of St. John arrived in Malta in 1530 they set up their base in the maritime town of Birgu and Fort St. Angelo. However from a strategic military point of view it soon became apparent that any defence of the Grand Harbour and Marsamxett necessitated a Fort at the tip of the Sceberras peninsula.

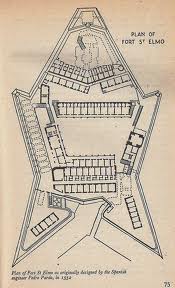

The Order was however in a dire financial situation and the first of a series of proposals to build a Fort on Mount Sciberras was made to the Grand Master De Homedes by Antonio Ferrandino da Bergamo in 1541. It was mainly due to the efforts of the Italian Knight, Fra Leone Strozzi, that Fort St. Elmo was finally constructed on the barren rock at the tip of Mount Sceberras.

In 1551 after a scathing attack by the Turks when they had pillaged and ransacked the island with hardly an opposition, Strozzi made a case for the immediate need to built a strong Fort to strengthen the harbour defences. On 8th January 1552, Grand Master Juan de Homedes instructed Fra Leone Strozzi together with Fra George Bombast, Fra Louis Lastic and Pietro Prato to design and supervise the construction of Fort St. Elmo. The designers of the Fort were only given six months, up till June, to complete its construction. The original chapel of St. Elmo was retained within the walls of the Fort.

.

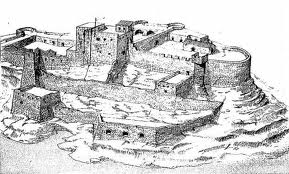

The Fort was a small star-shaped design with angled bastions. The walls were relatively thin and they were no higher than the level of the ground behind the Fort. The Fort lacked any outworks as is normally the case and its purpose was to defend against any invaders from the sea and it afforded no protection from any land invasion.

Undeniably, the most fascinating aspect of Fort St Elmo’s long and chequered history is the heroic role it played during the Great Siege of 1565. Fort Saint Elmo was the scene of some of the most intense fighting of the 1565 siege, and it withstood massive bombardment from Turkish cannon deployed on Mount Sciberras that overlooked the fort and from batteries on the north arm of Marsamextt Harbour, the present site of Fort Tigne. The initial garrison of the fort was around one hundred knights and seven hundred soldiers, including around four hundred Italian troops and sixty armed galley slaves. The garrison could be reinforced by boat from the forts across the Grand Harbour at Birgu and Senglea.

All other episodes in the fort’s saga pale in comparison. Yet, whilst the story of Fort St. Elmo’s epic resistance against the might of the Ottoman war machine is well known, the same cannot be said about many aspects of the structural and architectural elements that made up the very work of fortification itself. The fact of the matter remains that very little has actually survived, above ground, of the fabric of the original fort that took on the might of the Turkish onslaught during the initial stages of the Great Siege.

There are only but a handful of elements throughout the present enclosure that can be securely dated to 1565. In simple terms, few of the present day features actually witnessed the events of 1565. Work on Fort St Elmo began in 1552, following a Turkish razzia in 1551, and by the time of the Turkish investment in 1565, the fort had acquired a cavalier, a covertway, a tenaille and a ravelin, the last having been very hastily built in the months before the siege. Although the present day fort occupies much of the same footprint as the original structure, most of the 1552 fort and its outworks disappeared over the course of subsequent centuries. This was not only the result of the heavy Turkish bombardment, which pulverized whole sections of the revetments, scarps, and cavalier, but also the direct consequence of Francesco Laparelli’s rebuilding efforts in 1566 and, more radically, because of the heavy and significant alterations and additions that were made to enlarge and adapt Fort St Elmo in the course of the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which interventions produced the present layout and feel of the place.

Most of our information on the original 1552 fort, therefore, has come to us from documentary sources – a few laconic entries in the Order’s records, a couple of plans in the Simancas archives, Matteo Perez D’Aleccio’s colourful and artistic representations of the fort in his palace frescoes and prints, and Francesco Laparelli’s critical report prepared immediately after the siege

After valiantly holding out for more than a month during the Great Siege of 1565, Fort St. Elmo was completely destroyed.

During the bombardment of the fort, a cannon shot from Fort St Angelo across the Grand Harbour struck the ground close to the Turkish battery. Debris from the impact mortally injured the corsair and Ottoman admiral Dragut Reis, one of the most competent of the Ottoman commanders. The fort withstood the siege for over a month, falling to the Turks on 23 June 1565. None of the defending knights survived, and only nine of the Maltese defenders survived by swimming across to Fort St. Angelo on the other side of the Grand Harbour after Fort St Elmo fell.

Plans for rebuilding the Fort were taken in hand immediately after the Siege by the Italian military Francesco Laparelli. Laparelli designed the grid-iron street plan for a new city Valletta which was to be built on the Sceberras peninsula. The new Fort St. Elmo was one of the first structures to be completed. The original design in the form of a star was retained but with stronger walls and deeper ditches.

In 1689 a new series of Fortifications known as the Carafa bastions were designed by Don Carlos de Gruninberg and built under the supervision of the Order’s French military engineer, Mederico Blondel.

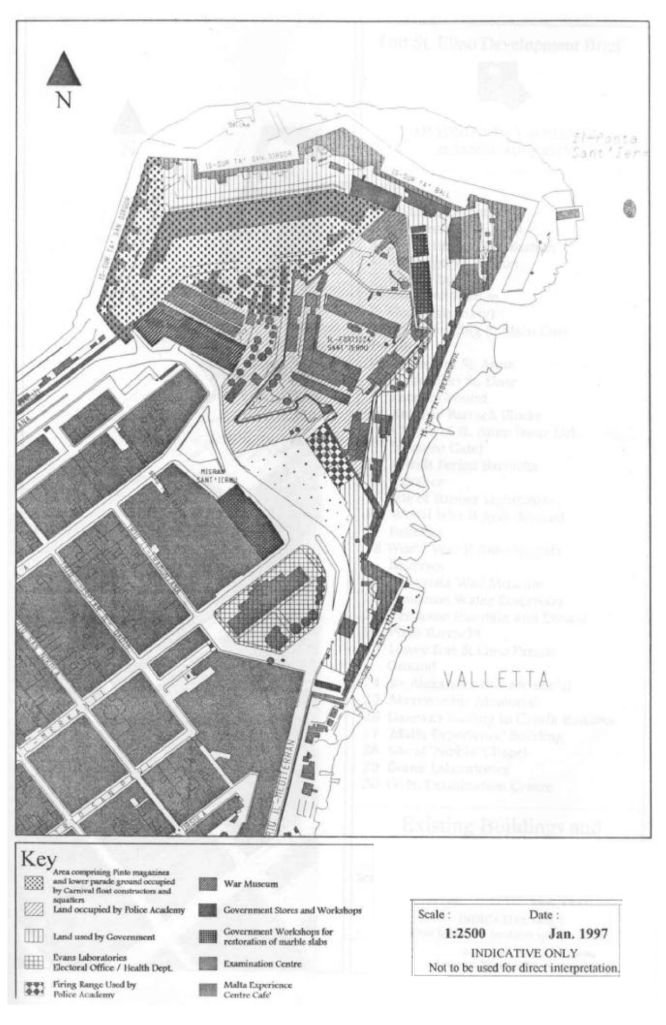

During the course of the eighteenth century various barracks were built around the internal piazza within the Fort. During the long reign of Grand Master Pinto (1741 – 1773), nineteen large vaulted magazines on three floors were constructed in the outworks along the Carafa Bastions. These structures were intended for the storage of food and as a shelter for women and children in the event of a siege.

Within the precincts of Fort St. Elmo are two religious buildings. The old chapel which had existed since 1488 was incorporated near the gate to the Fort, referred to as ‘del Soccorso’. The chapel was re-dedicated to St. Anne in the mid-sixteenth century. The church although of modest dimensions is embellished with ornate stone carvings that date to the seventeenth century. Another church also dedicated to St. Anne and which has an early eighteenth century Baroque facade overlooking the piazza was desecrated during the British period and its interior was completely remodelled.

During the early British Period a continuous musketry parapet was built, fitted with loopholes, continuing onto the adjacent Vendome battery. Between 1866 and 1877, the defensive outworks were strengthened by the construction of a series of gun emplacements and embrasures on the spurs of the Cavaliers facing the harbour.

In 1855 the polverista within Vendome Bastion was converted into a permanent armoury for the reception of small arms removed from the Palace Armoury. It was the outer ring of bastions and the cavalier which housed most of the heavy armament of Fort St. Elmo. Works were done on Abercrombie’s Bastion in the early 1870s.

During the inter-war period (1919-39) a number of gun emplacements were constructed to house the new twin 6-pdr QF guns.

It is important to say that during the first Italian attacks of 11 June 1940, six Maltese Royal Malta Artillery gunners lost their lives. However, the fort played an important part in the defeat of the Italian seaborne attack of 26 July 1941 on the Grand Harbour.

Within the bastion walls of Fort St. Elmo are buried two distinguished British officers who are General Sir Ralph Abercrombie and the first British Governor of the Malta, Sir Alexander Ball.

A circular stone light-house some 56 feet in height and a total of 206 feet above sea-level used to dominate the skyline of Fort St. Elmo and served as a guiding beacon to incoming ships. This lighthouse was demolished in 1940 for security reasons as it could have served as a landmark for the enemy aircraft World War II.

The ditch of the Fort used to house the Botanical Gardens which provided a source of medicinal plants for the School of Anatomy of the Order. These gardens were later transferred to Floriana by Sir Alexander Ball in the early nineteenth century.

Between 1988 and 2013 the Police Academy was accommodated within the precincts of Fort St. Elmo

The land-uses of the whole Fort St. Elmo complex and its environs in 2012

The land-uses of the whole Fort St. Elmo complex and its environs in 2012

Present day

The World Monuments Fund placed the fort on its 2008 Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites in the world because of its significant deterioration due to factors such as lack of maintenance and security, natural aging, and exposure to the elements.

In 2012 Heritage Malta started restoration and conservation works on Fort St Elmo.

Works at Fort St Elmo aimed at transforming the historical gem into an outstanding tourist attraction. The €15.5 million project, implemented by the Grand Harbour Regeneration Corporation in collaboration with Heritage Malta, was funded (85 per cent) by the European Regional Development Fund.

What is commonly referred to as Fort St Elmo actually consists of the fort, Carafa Enceinte (the outer parts of the fort) and Lower St Elmo (where parts of the 1978 film Midnight Express were filmed). The project incorporated Fort St Elmo and Carafa Enceinte. The fort, which was in an extreme state of deterioration, now includes a military history museum and a Valletta people’s museum. While the fort was being restored, some archaeological excavations were made and various elements of the original pre-1565 fort were uncovered. This was an important find because very little remains of the original fort exist, mainly since most of it was rebuilt by Laparelli in 1566 and it underwent a lot of renovation between the 17th and 19th centuries.

The military history museum spans from prehistory to present times and is located in various buildings throughout the fort. It also comprises a research centre and office and conference facilities. The Valletta people’s museum focuses on the sociological aspect of the city and is located in the Vendome Bastion. These two museums fall under the auspices of Heritage Malta.

A third attraction, termed “Rampart’s Walk”, is free of charge. This is a walk along the Enceinte and features an interpretation of historic structures and spectacular views of both harbours. The fort is dotted by a number of barcodes which people may scan with their smartphones or tablets to obtain instant information on the particular site or historical feature.

The fort’s ample spaces are also used for outdoor exhibitions, performances and re-enactments.

The project which was expected to be completed by September 2014 was officially opened on 8 May 2015.

In popular culture

Fort Saint Elmo was used as a film location for the Turkish jail in Midnight Express.

Popular Maltese folk band Etnika gave three concerts on 31 July, 1 and 2 August 2003 named Bumbum, that drew thousands of revellers to listen to modern Maltese folk music.

In the popular real time strategy game, Age of Empires III, the first level’s task is defend a fort on Malta against the Ottomans, which appears to be Fort St. Elmo.

Fort Saint Michael

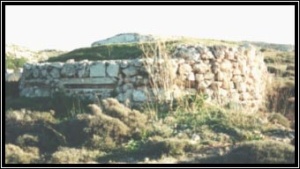

Fort St Michael is a fortification which is now destroyed except for the outer bastions which can still be seen to this day.

Fort St Michael is a fortification which is now destroyed except for the outer bastions which can still be seen to this day.

The fort was built by the Order of Saint John after the 1551 attack, on the peninsula then known as Isola di San Michele formed by Dockyard Creek and French Creek in Grand Harbour. The fortified city of Senglea which was later built around the fort is still known locally as l-Isla.

The original fort was begun in 1551, initially under the patronage of Grand Master Juan d’Homedes, to a design by the military engineer Pedro Pardo d’Andrera, and extended to a fortified city by Grand Master Claude de la Sengle during the Knights’ preparations for the Siege of Malta.

The fort’s design in very similar to that of Fort St. Elmo on the Sciberras Peninsula, with the exception of a bastioned front and a ravelin.

Fort St Michael was one of three forts defending the Knights stronghold in Grand Harbour during the siege, along with Fort St Elmo and Fort St Angelo. Fort St Elmo fell, but Fort St Michael withstood the siege, though massively damaged, the scene of some of the most desperate fighting of the siege. It withstood 10 assaults from the Ottoman Turkish attackers.

The rebuilding and development of the fortified city of Senglea after the siege continued until 1581. The name Fort St Michael became associated with the landward bastion of Senglea, also known as the St Michael Battery, or the St. Michael’s cavalier. This was largely dismantled during extensions to the dockyard area at the end of the 19th century and construction of a new primary school in the 1920s. The remainder was badly damaged by aerial bombing during the Siege of Malta during the Second World War. After the war the ruins were dismantled and the site made into a public garden.

However, the impressive seaward bastions of the fort remain, heir to Fort St Michael’s original site and purpose, as does the Senglea Main Gate, which has recently been restored, after the post war reconstruction collapsed in the late 1960s due to heavy rainfall.

Fort Ricasoli

The fort was built by the Knights of Malta between 1670 and 1693.

The fort was built by the Knights of Malta between 1670 and 1693.

It occupies the promontory known as Gallows Point that forms the eastern arm of Grand Harbour, and the north shore of Rinella Creek. Together with Fort St. Elmo and Fort Tigné it commands the approaches to Grand Harbour and Marsamxett Harbour.

History

It was designed by the Italian military engineer Antonio Maurizio Valperga, as part of Grand Master Nicholas Cottoner’s extensive fortifications around Grand Harbour. It is named for the knight who financed a large part of the works, Fra Giovanni Francesco Ricasoli.

The Fort continued to be an active military installation throughout the British period and was commissioned as HMS Ricasoli between 1947 and 1958, providing training for the Naval population..

It was the scene of a mutiny in 1807 when [Albanian] soldiers of the Froberg Regiment revolted and shut themselves up in Fort Ricasoli. Despite attempts at negotiation they eventually blew up the powder magazine. The mutiny was quashed by loyal troops, and 30 mutineers were condemned to death by court martial.

Fort Ricasoli was active in the defence of Malta during the second world war. Structural alterations and additional gun emplacements on the seaward bastion bear witness to its continued use and evolution as a military installation.

The fort has suffered significant damage from enemy action in the siege of Malta during World War II, when much of the internal structure was badly damaged. The gate has been rebuilt, but the internal buildings including the Governor’s House have been lost.

Present day

Today the fort faces a much bigger threat from the relentless onslaught of the sea. The fort is threatened by erosion from seaward, where a fault in the headland on which it stands is being eroded by the sea.

During the tenure of the British military, the bastion was substantially repaired, with the outer surface being cut back and new stone facing applied. This too is now eroding badly and in 2004 a section 100 metres long by 13 metres high was removed, restored and re-attached. Parts of the fort are still viewed as being in a dangerous condition.

Rihana Battery

Also known as Ducluseaux or Tal-Francis.

Rihana Battery was one of the original group of coastal fortifications erected by the knights of St John in the years 1714-16.

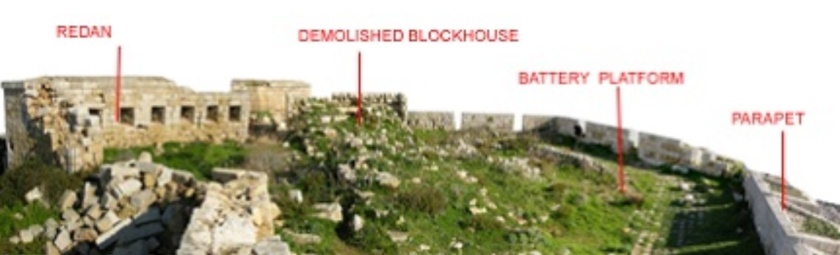

The structure originally consisted of a pentagonal platform with a large rectangular blockhouse sealing off the gorge. Today the structure is missing its left face, which collapsed over time into the sea.

The blockhouse itself originally had a V-shaped redan protecting its entrance (now missing) and a drop-ditch This was one of the largest blockhouses constructed in a Hospitaller coastal battery and consists of three rooms, a large central one for the accommodation of troops, with two smaller ones on the sides serving for the storage of gunpowder and victuals; in all the blockhouse’s roof was supported on 17 diaphragm arches and two cross-walls. The blockhouse has its own cistern cut out into the rock immediately underneath the floor of the building. There was one main entrance from the exterior and a corresponding opening leading out onto the battery platform. Each of the two side rooms had a door opening to the gun platform while the central room also had two windows, likewise opening onto the battery.

Various 19th and early twentieth century alterations were made to the blockhouse

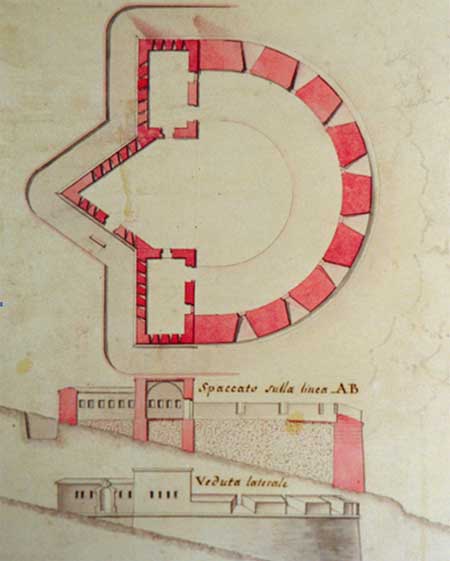

Santa Marija Battery, Comino

This battery was erected in 1715 to protect the south Comino channel, and is one of three surviving coastal batteries. It was equipped with two 24-pounder and four 6-pounder cannon. This type of coastal battery was built to resist the disembarkation of troops from an enemy fleet. It was fitted with a semi-circular enciente facing the entrance to the bay and contained eight embrasures as well as being enclosed by a wall that protected it from a landward attack. It also had a blockhouse to accommodate the garrison and to store ammunition and supplies.

Restoration of the Battery commenced in 1996. The project was completed with the installation of an iron gate to the main entrance, the blocking of six of the eight embrasures with an iron grill and the mounting of a 6-pounder cannon which was transferred from its location about four hundred metres away by helicopter in a joint operation between the Armed Forces of Malta and the Royal Navy. The original 24-pounder cannon were still on the island and have been mounted within the Battery. The stone in the embrasures and main entrance was badly deteriorated and the original pointing had suffered severe weathering. The roofs of the blockhouse need urgent repair and the entrance was about to collapse. Flagstones were laid in the three smaller rooms and the entire enciente was repointed.

Qolla il-Bajda Battery – Qbajjar Gozo

The battery on the promontory between Qbajjar and Xwejni is the last vestige of a chain of fortifications built early in the eighteenth century around Marsalforn bay to avoid landings of enemy craft in the area.

Known commonly, but wrongly, as Qbajjar Tower, this battery was raised between 1715 and 1716 under the direction of the military engineers Jacques de Camus D’ Arginy and Bernard de Fontet.

The battery is constructed in a semi-circle with two blocks to house the garrison and a defensive wall between them with musketry loopholes to provide enfiladed fire.

There is a ditch on the seaward side and access was from the landward side through a high stairway with a drawbridge.

The battery’s armament in 1770 was four 6-pdr. guns with 276 rounds of roundshot and 60 rounds of grapeshot.

Fort Manoel

Fort Manoel stands on Manoel Island in Marsamxett Harbour to the north west of Valletta and commands the entrance to Marsamxett Harbour and the anchorage of Sliema Creek. Fort Manoel is a star fort with much of its ditches and walls formed from the native rock of Manoel Island.

History

The fort was built by the Knights of Malta between 1723 and 1755, under the patronage of Portuguese Grand Master Manoel de Vilhena.

The original design work for a fort on the island, then known as Isolotto, was the work of the French engineer René Jacob de Tigné. The final design also incorporated the work of Charles François de Mondion, at that time the Knights of Malts’s resident military engineer in charge of works of fortification and defence. Mondion also supervised the construction, and was hypothetically buried in the fort’s chapel, St. Anthony’s Chapel.

The original design work for a fort on the island, then known as Isolotto, was the work of the French engineer René Jacob de Tigné. The final design also incorporated the work of Charles François de Mondion, at that time the Knights of Malts’s resident military engineer in charge of works of fortification and defence. Mondion also supervised the construction, and was hypothetically buried in the fort’s chapel, St. Anthony’s Chapel.

The fort was an active military establishment initially under the Knights and later under British Military control from its construction through until 1906 when the British military finally decommissioned the forts guns.

During the Second World War, a battery of 3.7-inch heavy anti-aircraft guns was deployed in and around the fort. The guns were mounted in concrete gun emplacements and deployed in a semicircle around the fort. The fort suffered considerable damage to its ramparts, barracks and chapel as a result of aerial bombing during the war.

In 2010, the fort underwent major restoration work to repair the ravages of time and damage sustained during the Second World War.

It served as a location for the shooting of the climactic scene of the episode Baelor of the TV series Game of Thrones. This was one of the strongest fortifications.

St Anthony Battery – Qala Gozo

The first proposal for the fortification of the Qala location was put forward in 1730 and the work on the battery, named St Anthony Battery in honour of the then-reigning Grand Master, Antoine Manoel de Vilhena (reigned 1722-36), who had offered to build it out of his own expense, was began in 1731 and brought to completion in the following year, as recorded by the date and inscription which once stood above the small main gate into the fort.

The major structural work on St Anthony Battery seems to have been completed by early December of 1732 as evidenced by the fact that the remaining surplus quantities of pozzlana (a type of volcanic ash used in the mixture of lime mortar) were removed from the battery on 28 December 1732, and transported back to the Gozo citadel, a task which cost the Governor of Gozo 8 tari ( ‘per trasporto della puzzolana avvanzata in detto fortino, nel Castello’). Many of the finishing touches, however, were still under way during 1733 and continued as late as April 1734 when the escutcheons on the main gate were finally carved out. In August 1733, the master carpenter Antonio Mallia and the master blacksmith Saverio Dimech received payment for the manufacture and fitting of the doors and windows of the blockhouse while towards the end of that year Mastri Ferdinando Vella and Domenico Bigeni were paid for other unspecified works carried out at the battery. By this time, the battery was already in need of some repairs. Two large stones supporting the drawbridge had to be replaced, for the cost of 1 scudo, after being damaged during the transportation of the heavy cannon into the battery on 20 December 1732 (‘per rimetter due ballate al ponte di detta batteria (qala) quail furon rotte quando vi si trasporto l’artigliaria). The roof of the block house had to be repaired twice, in February and September 1733 respectively.

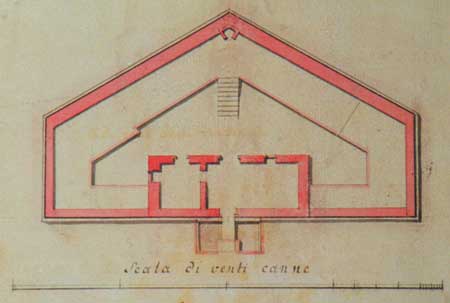

The Ras il-Qala battery was one of the largest coastal batteries constructed locally in terms of its typology and dimensions. Its design is also unique in many ways. To begin with, its polygonal plan departed from the standard semi-circular configuration which was nearly universally applied to most coastal batteries of the time, particularly those erected by the knights during the course of the 1700s. The platform has a demi-hexagonal plan with a large musketry wall and triangular redan closing off the gorge, complemented by a sizeable centrally-placed blockhouse occupying the rear of the platform. The design of the battery is attributed to the resident military engineer, the Frenchman Charles Francois de Mondion, which would make it one of his last works, given that he died in 1733. As resident military engineer, Mondion would have been responsible for all new works of fortification but the construction works would have been supervised by his assistant, the Italian second engineer Francesco Marandon, who would later go on to become the resident military engineer in his own right and see to the construction of the large fortress on Ras-e-tafal (Fort Chambrai) in 1749.

Initially, it was intended to arm the battery with a good number of heavy guns, including among others, two 36-pounders (then amongst the heavies pieces in the Order’s arsenal), together with other 24-pounders. Indeed, the ammunition for these guns had already been transported and deposited inside the battery by the end of 1731 when it was suddenly decided to arm the battery with guns of a smaller calibre. In December 1732, the extra sum of 9 scudi had, as a result, to be incurred ‘per portare palle di ferro nella batteria d Ras il Cala in lugo di quelle divenute inutile allorche furono mutate i cannoni’.

For most of its history, Qala Battery was to have an armament of eight guns. By 1785, these included five 8-pounder iron cannon with 420 rounds of roundshot and 58 rounds of grapeshot; and three 6-pounder guns with 175 rounds of roundshot and 61 rounds of grapeshot. The importance of the battery can be gauged by the fact that it was one of the few coastal works to have held its own supply of gunpowder permanently on site; which in turn also meant that the outpost was manned round the clock, all year round

Mistra Battery

Although the building of a battery was mentioned in the report prepared by the commissioners of fortifications Fontet and D’Arginy, it seems that this battery was not built in 1714.

In fact Maigret’s report written in 1716 does not mention this battery.

Probably the battery was built in 1761 on the insistence of the military engineer Bourlamaque. During this period there was Grand Master Manoel Pinto de Fonseca and there was a revival in the building of new coastal fortifications. These were the coastal entrenchments.

Bourlamaque also emphasised on the building of new coastal batteries and Mistra Battery seems to be one of them.

Mistra battery consists of a large semi-circular artillery platform surrounded by a low parapet.

Originally there were three embrasures in this battery. The battery was surrounded with a ditch. At the rear of the battery there are two blockhouses and on the landward side of the walls there are a number of musketry loopholes to cover the inland approaches. The blockhouses are linked with a redan. It is interesting to note that the redan was fitted with an upper walkway for the sentinels stationed in this battery. One can immediately recognise that the idea of this walkway is similar to that of the bastions. In the redan there the door where was there was a small drawbridge over the ditch.

Over the door there is the coat-of-arms of Bailli de Montagnac and Grand Master Pinto, thus bringing one to the conclusion that this battery was built during his reign. In 1770 there was one 8-pdr as artillery in the battery.

From early 1990s till 2012 Mistra Battery was used as a fish-farm, where a number of alterations were made on it, destroying also parts of it. It was restored in 2012 after the fish farm was relocated.

Fort Tigne’

Fort Tigné was begun in 1793 and was a very small work by eighteenth century standards, actually more of a large redoubt, but its design was probably the most revolutionary and influential of all the fortifications built by the knights in Malta.

Fort Tigné was begun in 1793 and was a very small work by eighteenth century standards, actually more of a large redoubt, but its design was probably the most revolutionary and influential of all the fortifications built by the knights in Malta.

Designed by the Order’s chief engineer, Stephan de Tousard, its most important features were the lack of bastions and the counterscarp musketry galleries. The design was heavily influenced by the writings of Montalembert and more particularly by the lunettes built by the French general, Jean-Claude Lemichaud D’Arçon.

By the end of the eighteenth century, the supremacy of the bastioned system was being challenged by the growing popularity of the tenaille trace. The new style of fortification known as the polygonal system, of which Fort Tigné is one of the earliest examples, was to dominate the art of military architecture through most of the following century.

Fort Tigné was the last major work of fortification built by the Order in Malta.

18th Century Coastal Batteries

Dr Stephen Spiteri

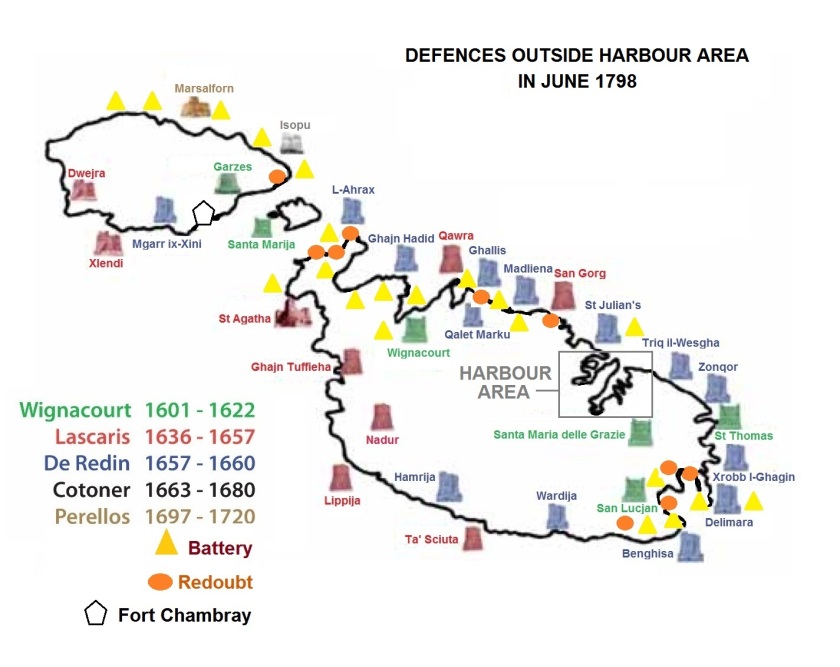

Coastal fortifications were an important component of the Order’s defensive strategy throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Initially, the Hospitaller defensive scheme was conceived as a sort of early-warning system intended to warn of approaching danger but this strategy was eventually augmented, by the end of the eighteenth century, with a wider network of defensive positions redesigned to serve as a series of physical obstacles against invasion.

When the knights took possession of the Maltese islands in 1530, they were unwilling to construct any but the most essential defensive works and, right up to the end of the cinquecento, the Order confined its attention primarily to the fortification of the harbour area. As far as the defence of the coastline was concerned, the Hospitallers continued to rely upon the same system of militia watch-posts that had long since been employed by the Maltese. Few military outposts were erected beyond the Harbour area until the turn of the seventeenth century when the knights embarked upon a spree of tower-building but it was the eighteenth century, however, which was to witness the heaviest and most widespread investment in coastal works of fortification. Between 1714 and 1716, the Order’s French military engineers designed and built a vast network of coastal defensive positions comprising a network batteries, redoubts, and entrenchments. Unlike the towers, however, these new elements were designed to actively resist invasion and provide solid barriers to attack, reflecting a deliberate change in strategy that was to remain the Hospitaller knights’ main concern throughout the course of the settecento.

Most of the coastal fortifications, particularly the batteries and redoubts, were built in the manner of permanent stone fortifications, along formal lines with revetments of carefully cut stone although, many others, particularly the coastal entrenchments, were built more hurriedly in the manner of field defences.

The first to materialize were the coastal batteries, or platforms, designed to mount guns intended to fire on approaching ships. Although many of the batteries which took root around the islands’ shores materialized in the years 1715–16, the idea for these French style coastal defences had been first mooted by the Commissioners Jacques de Camus d’Arginy and Bernard de Fontet and a French secondary engineer by the name of François Bachelieu in 1714. The coastal defence strategy found a great exponent in the Prior of France, the Balì de Vendôme, and it was mainly through the latter’s insistence, and a generous loan of 40,000 scudi which he presented to the Order, that the network of batteries and redoubts was made possible. A number of other knights too, made small financial donations toward this effort – as can be witnessed by the fact that a number were named after their benefactors, such as Arrias Battery, Crevelli Redoubt, Ferretti Battery, Gironda Battery, etc.

Initially, it appears that these were simply prepared positions for artillery, undefended and open to the rear but most soon began to acquire defensible perimeters and blockhouses to shelter troops and munitions. Most of these structures followed the French pattern, albeit on a smaller scale, and basically consisted of semi-circular or polygonal gun-platform, sometimes ringed by embrasured parapets, and having one or two small blockhouses. For protection from landward attack, the batteries were given loopholed walls and redans. In most cases the blockhouses were placed in such a manner as to seal off the gorge and their walls were pierced with musketry loopholes. The engineers experimented with various combinations of blockhouses and redans depending on the tactical requirements of the site. In two instances, at Mellieħa (Westreme Battery) and Comino, a single blockhouse was placed diagonally across the gorge so that its two outer faces functioned as a redan. Some batteries were also protected by rock-hewn ditches placed either on the landward or seaward sides, or both. Those batteries built very close to the sea, like Orsi, Qajjenza, and Buġibba had moats filled with water.

The entrance to all batteries was from the landward side. A drawbridge was usually fitted to the gateway but it seems that not all batteries were actually fitted with one since, in 1792, the Congregation of Fortification and War ordered that those still lacking a drawbridge were to be supplied instead with two wooden planks.

Design-wise, hardly any two batteries are the same. They all differed in some detail from one another, either in size, shape of the artillery platform, number of embrasures on the parapet, or the layout of the barrack blocks and landward defences. This variety may reflect the personal preferences of the relatively large number of military engineers who were present on the island in the years 1714–16.

A variant of the coastal battery, was the coastal redoubt. In shape and form, there was little to distinguish a Hospitaller coastal redoubt from a coastal battery other than that the former usually lacked embrasures and gun platforms for cannon, for both were equipped with blockhouses and ditches. Unlike the batteries, however, the majority of redoubts erected by the knights in Malta and Gozo followed a more or less standard pentagonal plan. The redoubts were not generally designed to mount cannon since they were intended to serve as infantry strongpoints. Tactically, they were designed to allow small detachments of militia equipped with muskets to hold out against landed troops and prevent them from establishing a beachhead. The defensive roles played by redoubts varied considerably, making it difficult to give a precise definition and any particular configuration to this form of fortification.

The pentagonal-plan redoubts were all fitted with a single blockhouse at the gorge and had low parapets and all-round shallow ditches. Eleven redoubts were built following this standard pattern. The majority are found along the northern shores of Malta from Baħar-iċ-Ċaghaq to Marfa, (Tal-Bir, Eskalar, Armier, Louvier, Mellieħa, Qalet Marku, and Baħar-iċ-Ċagħaq) together with two in Gozo (Marsalforn and Ramla). Only two were built in the south of Malta, namely at Marsascala and Marsaxlokk (Del Fango Redoubt). A few coastal redoubts were built with semicircular or rectangular platforms such as St George Bay Redoubt, Xwejni Redoubt in Gozo, St George Redoubt (Birżebbuġa), and the two Salina Bay redoubts. That known as the Perellos Redoubt, at Salina (now demolished), was particular in that one corner of its perimeter wall was fitted with a small bastion. Ximenes Redoubt, on the opposite side of the bay, on the other hand, had two blockhouses but these were later unceremoniously replaced by a large magazine designed to house salt from the nearby Saline Nuove. Both Salina redoubts were unique in that they were later also fitted with internally-placed fougasses. The most sophisticated redoubts, certainly, were the tower-like works pierced with rows of musketry loopholes. These were designed along the lines of blockhouses or tour-reduits, a type of fortification much favoured by the French throughout their colonies in the Americas, where most were built in wood. In all, three tour-reduits were built and these were confined to Marsaxlokk Bay, namely Fresnoy, Spinola, and Vendôme Redoubts. The Spinola and Vendôme tower-redoubts were squarish in plan but that at Kalafrana (Fresnoy), had a semicircular front and a redan to the rear facing the landward approaches. Only the Vendôme example survives to this day. A fourth tour-reduit was erected in 1720 at Marsalforn in Gozo, presumably by Mondion, but this too, has disappeared.

BRITISH ERA

Some Fortifications and Batteries

Fort Leonardo

Fort Leonardo also known as Fort St Leonardo, Fort San Leonardo and Fort San Anard is a fortification that stands between Xghajra and Zonqor Point above the shore east of Grand Harbour.

Fort Leonardo also known as Fort St Leonardo, Fort San Leonardo and Fort San Anard is a fortification that stands between Xghajra and Zonqor Point above the shore east of Grand Harbour.

It was built between 1872 and 1878 by the British.

Fort St Leonardo still exists, and is in reasonable repair, though a house has been built inside the ditch and the ditch in-filled to create an access. The seaward ditches are all in good repair. The fort is now used as a farm.

The layout of the fort is complicated, with a smaller inner fort forming one corner within the larger part of the fort that contains the gun emplacements.

A modern construction, possibly a reservoir, alongside the shoreward side of the fort detracts rather from its original appearance, and the approach to the main gate has been mined for rubble and is substantially damaged.

The fort inside the ditch is not open to the public.

Fort St. Rocco

Fort St Rocco, also known as Fort St Roca on some maps, is a fortification that stands east of the Rinella Battery and seaward of Xghajra, and forms part of the complex of shore batteries defending the coast east of the mouth of Grand Harbour.

Its construction was started in 1872 by the British, as part of a program of improvements to Malta’s fortifications recommended in Colonel Jervois’s Report of 1866 titled “Memorandum with reference to the improvements to the defences of Malta and Gibraltar, rendered necessary by the introduction of Iron Plated Ships and powerful rifled guns“.

It remained a functional military establishment until the 1950s.

Fort Sliema

Sliema Point Battery, or as known by the Maltese “Il-Fortizza”, was completed in 1876 to the design of Colonel Jervois, who incorporated many Gothic features.

Sliema Point Battery, or as known by the Maltese “Il-Fortizza”, was completed in 1876 to the design of Colonel Jervois, who incorporated many Gothic features.

It was armed with four canons and the total cost was £12,000.

By 1903, the guns were removed and the fort became a searchlight position to illuminate any enemy vessels approaching the island, especially the Grand Harbour area.

Fort Pembroke

The largest British coastal defence in Pembroke is Fort Pembroke. It was built between 1875 and 1878 on the high ridge overlooking the northerly seaward approach to the Grand Harbour. Its main armaments were three 11-inch Rifle Muzzle Loading guns and one 64-pdr gun, all mounted ‘en barbette’ (a protective circular concrete emplacement around a gun that fired over the top of the parapet).

The largest British coastal defence in Pembroke is Fort Pembroke. It was built between 1875 and 1878 on the high ridge overlooking the northerly seaward approach to the Grand Harbour. Its main armaments were three 11-inch Rifle Muzzle Loading guns and one 64-pdr gun, all mounted ‘en barbette’ (a protective circular concrete emplacement around a gun that fired over the top of the parapet).

The fort was shaped like an elongated hexagon surrounded by a ditch and glacis and contains underground magazines and casemated quarters for the garrison.

By the mid-1890s, the fort’s armament were considered obsolete and required replacement but the change never materialized and the use of the fort became more of a depot and storage area, especially for small arms ammunition. Later, the gate was widened, it’s rolling Guthrie Bridge was dismantled and replaced by a fixed metal bridge.

Following the closure of the Pembroke military establishments in 1978, the fort remained unused for some time but later it was allocated for use as the Verdala International School which still operates from this historic site.

MEPA scheduled Fort Pembroke in 1996 as Grade 1 property of historic, architectural and contextual value as it forms part of a larger scheduled military complex. In 2009 its protection status was revised to also include its surviving glacis as republished in the Government Notice number 880/09 dated 30th October, 2009.

Fort Delimara

History

The fort was built between 1876 and 1888 by the British. The main gate carries a date of 1881, but this is the date of completion of the gatehouse, not the commissioning of the fort.

The fort was built between 1876 and 1888 by the British. The main gate carries a date of 1881, but this is the date of completion of the gatehouse, not the commissioning of the fort.

Fort Delimara was a one of a ring of forts and batteries that protected Marsaxlokk harbour, along with Fort Tas-Silg at the shoreward end of Delimara point, Fort St Lucian on Kbira point in the middle of Marsaxlokk bay, Fort Benghisa on Benghisa Point, and the Pinto and Ferreti batteries on the shores of Marsaxlokk Bay.

In 1956 the fort was stripped of the majority of its artillery. Soon after, the fort was abandoned for a considerable period, and in 1975 it was leased by the Malta Government to a local farmer, who used it to raise pigs for fifteen years.

After protracted negotiations, ownership of Fort Delimara was transferred to Heritage Malta on August 11, 2005. Despite the pigs and a considerable amount of modern debris, the fort remains in decent condition, and still retains four of its original complement of fourteen Victorian 12.5-inch 38 ton rifled muzzle-loading guns.

Heritage Malta intends to restore the site to its former condition, and open it to the public as a museum and tourist site.

Details of the fort

Fort Delimara is mostly underground, with the fort’s main armament mounted in casemates set in the cliffs on the shoreward face of Delimara Point. At the surface it is a polygonal fort, rectangular in outline, with rock cut ditches on three sides, and the gently curving vertical cliff forming the convex fourth side. Ventilation apertures and access passageways are spread out across the face of the cliff, and even out onto the seaward face of Point Delimara.

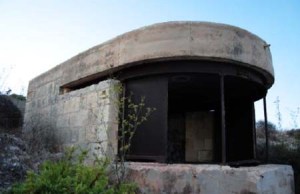

Gatehouse

The ditches are edged with revetting, with the upper scarp faced in earth and rubble. A stone parapet with rifle loops runs along the top of the north scarp. A square building above the gate may be a later addition from the early twentieth century, when the fort was used as a military base long after its surface fortifications were obsolete. A World War II vintage pillbox has been erected inside the Victorian fortification, and shows above the fort’s profile when viewed from the sea. The gatehouse faces toward the landward end of Delimara Point, reached by a tarmac road that runs outside the north ditch. The gatehouse is close to the seaward end of the north ditch.

The ditches are edged with revetting, with the upper scarp faced in earth and rubble. A stone parapet with rifle loops runs along the top of the north scarp. A square building above the gate may be a later addition from the early twentieth century, when the fort was used as a military base long after its surface fortifications were obsolete. A World War II vintage pillbox has been erected inside the Victorian fortification, and shows above the fort’s profile when viewed from the sea. The gatehouse faces toward the landward end of Delimara Point, reached by a tarmac road that runs outside the north ditch. The gatehouse is close to the seaward end of the north ditch.

Counterscarp battery

A counterscarp battery at the north end of the east ditch commands the north ditch and the gatehouse. Presumably there is a counterscarp battery at the south end of the east ditch covering the south ditch, since there are no caponniers visible in the ditch.

East and south ditches

The glacis in front of the gatehouse has probably been reduced at some time to make road access easier, and the rolling bridge that would originally have crossed the ditch has been replaced by a permanent bridge. The road to Delimara Lighthouse along the east ditch of the fort disrupts the glacis on this face as well. The glacis is more intact along the south ditch, giving a better impression of how the fort would have looked when originally built.

Seaward face and gun emplacements

The seaward face of the fort is dominated by the massive stone and concrete casemates that originally sheltered the fort’s 12.5 inch rifled muzzle loading guns. The casemates are grouped in pairs close to the cliff top, capped by an earth and rubble slope, and follow the natural curve of the cliff face, giving them a combined field of fire that covers the majority of Marsaxlokk harbour.

Present condition

Externally the fort is in fair condition. Like all the polygonal forts in Malta, the limestone faces of the scarp and counterscarp have eroded substantially since they were originally cut, in places to a depth of as much as a metre. In some cases this erosion has reached the point that the revetting collapses into the ditch. Where the road to Delimara Lighthouse runs along the east ditch of the fort, directly above the counterscarp face of the ditch a section of perhaps ten metres the counterscarp has collapsed into the ditch, and threatens the stability of the road. The resulting rubble fall can be seen in the image of the east ditch. The ditch is also considerably overgrown, and polluted with general rubbish, unfortunately true of all the Victorian forts in Malta. There is currently no public access to the interior of the fort.

Fort Rinella

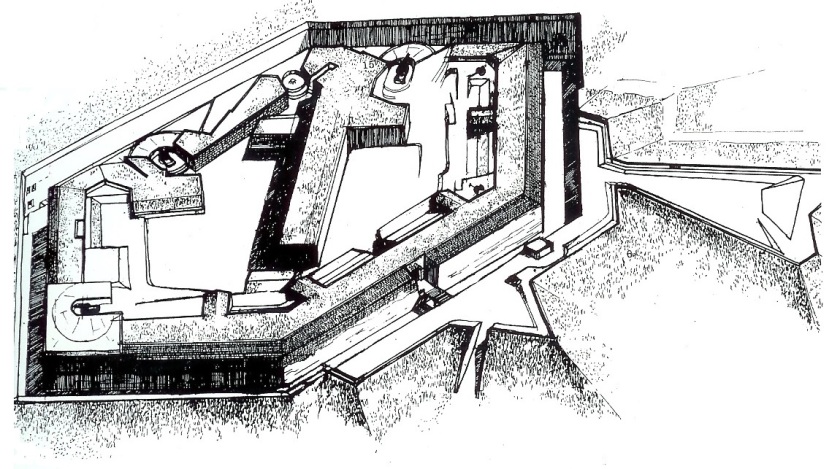

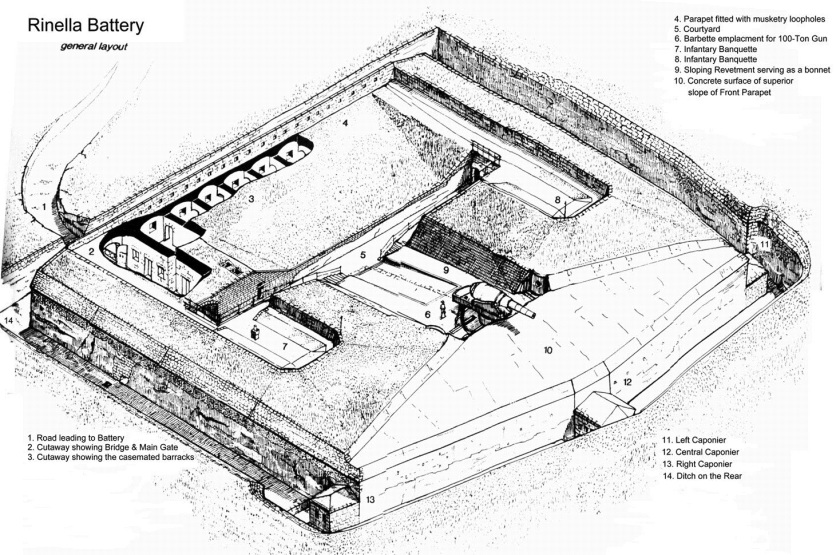

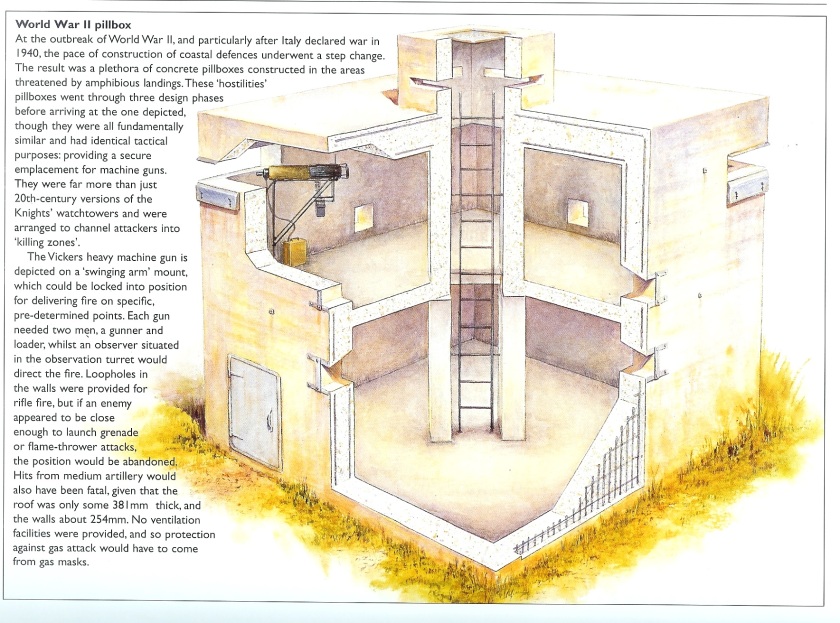

Fort Rinella is a Victorian fortification which is also referred to as the Rinella Battery in some maps and publications.

Fort Rinella is a Victorian fortification which is also referred to as the Rinella Battery in some maps and publications.

History

The British built the fort between 1878 and 1886, which stands above the shore east of the mouth of Grand Harbour, between Fort Ricassoli and Fort St. Rocco.

The fort was built to contain a single RML 17.72 inch gun: a rifled muzzle loading gun weighing 100 tons made by the Elswick Ordnance Company, which is still in place. The fort was originally one of a pair, however the paired Cambridge Battery near Tigne, west of Grand Harbour, no longer exists. The British installed a second pair of guns to defend Gibraltar, mounting one each in Victoria Battery (1879) and Napier of Magdala Battery (1883), which did not have Rinella’s self-defence capabilities. Today, only two of these guns survive, the one at Fort Rinella and the one at Napier of Magdala Battery.

The British felt the need for such large guns as a response to the Italians having, in 1873, built the battleships Duilio and Dandalo with 22 inches of steel armour and four similarly large 100-ton Armstrong guns per vessel. By arming both Gibraltar and Malta, the British were seeking to ensure the vital route to India through the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal, which had opened to traffic in 1869.

The fort is modest in size as it was designed to operate and protect the single large gun, with its associated gun crew, magazines, bunkers, support machinery and the detachment of troops stationed within the fort to defend the installation.

The gun was mounted en barbette on a wrought-iron sliding carriage and gun fired over the top of the parapet of the emplacement. This enabled the gun-crew to handle and fire the gun without exposing themselves to enemy fire. The fort was designed to engage enemy warships at ranges up to 7,000 yards. The low profile of the fort and the deeply buried machinery rooms and magazines were intended to enable it to survive counterfire from capital warships.

The fort has no secondary armament; its fortifications – simply ditches, caponiers, a counter-scarp gallery and firing points – were intended mostly for small arms fire and grenades.

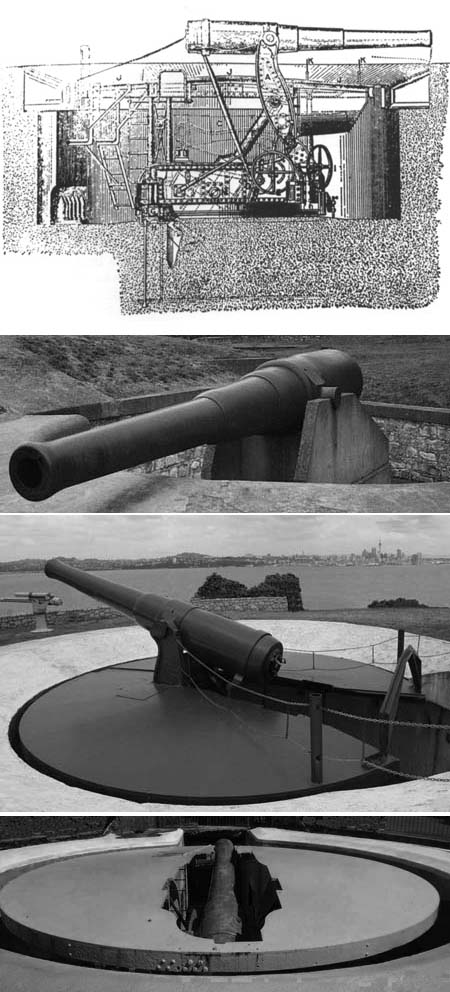

The massive gun is far too heavy to be laid by hand, and the fort therefore contained a steam powered hydraulic system that traversed, elevated and depressed the gun, operated a pair of hydraulic powered loading and washing systems, and powered the shell lifts that moved the 2,000-pound shells and 450-pound black-powder charges from the magazines into the loading chambers.

The gun was intended to operate at a rate of fire of a single shell every six minutes. The firing cycle was for the gun to be traversed and depressed until it aligned with one of loading casemates, with the barrel pushing aside an iron plate that normally closed the aperture in the casemate. The gun was then flushed with water to cool it, clean any debris and deposit from the barrel, and douse any remaining embers from the previous cartridge. The ramming mechanism then inserted and tamped a silk cartridge containing the propellant charge, which was followed by one of the range of shells the gun was adapted to fire. The loaded gun was then traversed and elevated using the hydraulic system, and fired by an electrical firing mechanism. The gun then slewed to the other casemate to repeat the loading process, while the first casemate was recharged from the deeper magazine.

The gun was intended to operate at a rate of fire of a single shell every six minutes. The firing cycle was for the gun to be traversed and depressed until it aligned with one of loading casemates, with the barrel pushing aside an iron plate that normally closed the aperture in the casemate. The gun was then flushed with water to cool it, clean any debris and deposit from the barrel, and douse any remaining embers from the previous cartridge. The ramming mechanism then inserted and tamped a silk cartridge containing the propellant charge, which was followed by one of the range of shells the gun was adapted to fire. The loaded gun was then traversed and elevated using the hydraulic system, and fired by an electrical firing mechanism. The gun then slewed to the other casemate to repeat the loading process, while the first casemate was recharged from the deeper magazine.

The two separate loading casemates, each fed by an independent magazine, and the provision of man-powered backup pumps for the hydraulic system, such that a team of 40 men could maintain the hydraulic pressure to operate the gun, would have allowed the fort to continue firing even if substantially damaged.

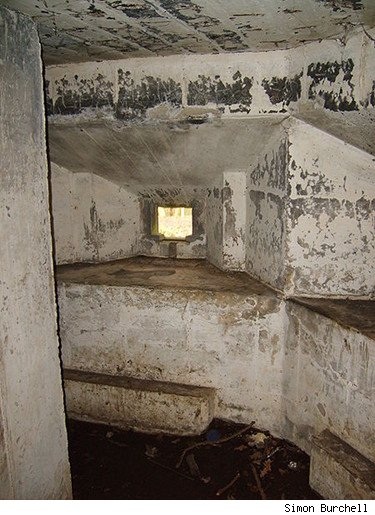

Originally the inner faces of the emplacement were revetted with masonry. Subsequent review of the fort’s defences after its completion identified this as a weakness, and the stone revetting was removed from most of the emplacement and replaced with plain earthworks, presumably to better absorb the energy of incoming shellfire. The revetting was retained around the loading casemates, as one can see in the image above.

Originally the inner faces of the emplacement were revetted with masonry. Subsequent review of the fort’s defences after its completion identified this as a weakness, and the stone revetting was removed from most of the emplacement and replaced with plain earthworks, presumably to better absorb the energy of incoming shellfire. The revetting was retained around the loading casemates, as one can see in the image above.

The 100 ton guns were in active service for only 20 years, with all being withdrawn from active service by 1906, without ever firing a shot in anger. Because a single shell cost as much as the daily wage of 2600 soldiers, practice firing was limited to one shot every 3 months.

After the Armstrong gun was retired from service, Fort Rinella was used as an observation post for the guns of Ricasoli Fort, and unfortunately at some point the now obsolete steam engine and hydraulic system were removed. During World War II, the Navy used the Fort to store supplies, and it received seven bomb hits. The fort was ideal because from a plane’s view it blends into the fields as it was covered in moss and grass. The Navy gave up the site in 1956.

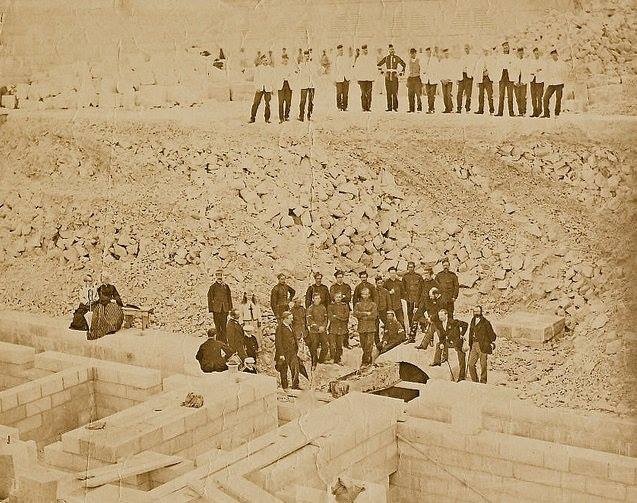

Emplacing the gun

The 100-ton gun arrived in Malta from Woolwich on 10 September 1882. There it sat at the dockyards for some months before it was ferried to Rinella Bay. One hundred men from the Royal Artillery manhandled it to the fort in a process that took some three months. The gun was finally in position and ready for use in January 1884.

Fort Rinella today

Since 1991, the Fondazzjoni Wirt Artna has been restoring the fort, which is now open to the public as a Museum. Unfortunately, the steam engine and hydraulic machinery have not yet been replaced. Once a year, in May, a crew of volunteers fires the gun (using only black powder) to keep it active, and also to attract more visitors.

Since 1991, the Fondazzjoni Wirt Artna has been restoring the fort, which is now open to the public as a Museum. Unfortunately, the steam engine and hydraulic machinery have not yet been replaced. Once a year, in May, a crew of volunteers fires the gun (using only black powder) to keep it active, and also to attract more visitors.

Throughout the year, at 13.00pm, re-enactors dressed as 19th Century British soldiers provide a tour of the fort that combines lecture, demonstration and live re-enactment. This includes the firing, without shot, of a Victorian-era muzzle-loading fieldpiece.

In the 1960/70s, the Fort was used as a location in the films, Zeppelin, Shout at the Devil, and Young Winston.

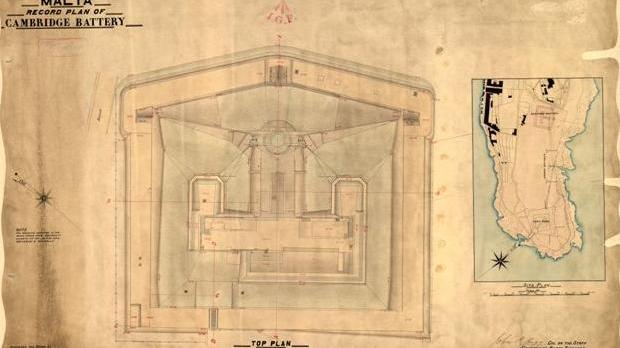

Fort Cambridge

The Cambridge Battery is a fortification in Malta . It was built from 1878 to 1880 at the time of British rule. It is located on the north east coast of the Dragut’s Point headland above the north entrance of Marsamxett Harbour immediately next to Fort Tigne’ . It was used to house the RML 17.72 inch gun.

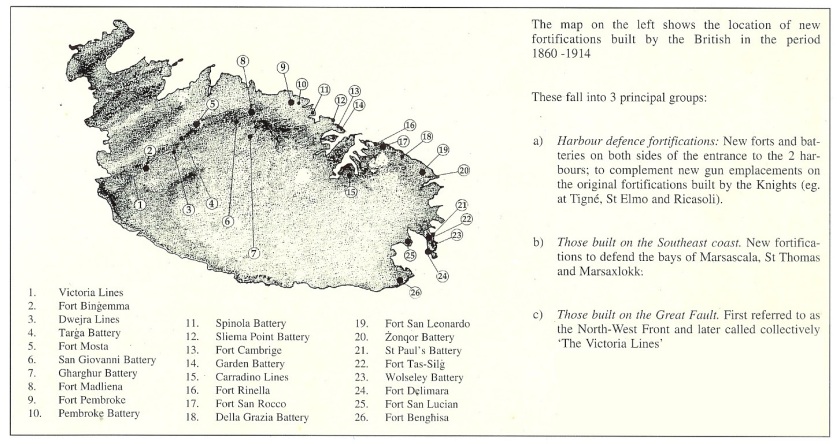

When the British took over Malta in 1800 it was considered that the Fortifications left by the Knights of St John and the presence of the British Royal Navy in the Mediterranean was enough to defend the Maltese Islands.

However this scenario changed with the founding of the Regia Marina Italiana on 17 March 1861. The Regia Marina in 1873 inaugurated the battleships Caio Duilio and Dandolo Enrico. Equipped with four 450 mm cannon and heavily armoured, they were 15 knots faster than the British ships of that era.

The emerging development made it clear that the fortifications of Malta had to be reinforced. The construction of the Rinella and Cambridge Batteries together with the strengthening of fortifications in the area of the Grand Harbour were given the highest priority.

The first cannon was transferred to the Cambridge Battery on 16 September 1882. By 20 February 1884 it was operable . However because of outstanding works it could be used only in 1885. Between 1887 and 1888, the gun’s use was limited by problems of hydraulic systems. However, the weapons were judged to be quite reliable. The cannon was decommissioned in 1906, although the last time it was fired was in 1903 or 1904.

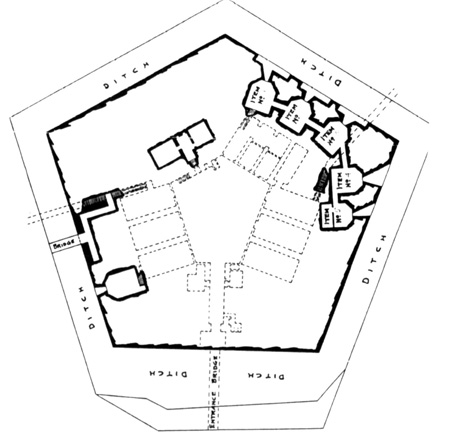

The Cambridge and the Rinella Batteries are identical. Both have the shape of a pentagon with a width of 71 m and a height of 66 m. The ramparts of the battery is about 6 m thick. The whole area was surrounded by a 5 m wide trench.

The system consisted of two storeys. The upper floor was the only protected by a relatively low parapet firing position. On the lower floor there were two ammunition bunkers and the steam engine to drive the hydraulic directional drives of the guns.

The crew consisted of 35 men, of whom 18 were needed to reload the gun.

The construction cost of the facility was 18,890 British pounds.

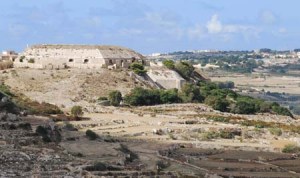

Fort Tas-Silġ

This fort was built between 1879 and 1883 as a redoubt to command the higher ground of the Delimara Headland above Il-Ħofra-z-Zgħira. Its armament consisted of six 64pr RML guns on Moncrieff disappearing carriages.

This fort was built between 1879 and 1883 as a redoubt to command the higher ground of the Delimara Headland above Il-Ħofra-z-Zgħira. Its armament consisted of six 64pr RML guns on Moncrieff disappearing carriages.

It is a Polygonal fort and was built by the British. Its primary function was as a fire control point controlling the massed guns of Fort Delimara on the headland below.

The fort is a classic example of the type. The gatehouse, and the shoreward ditch are in fair repair, but there has been considerable collapse of the inner face of the north ditch.

Fort Tas-Silġ is one of a ring of forts and batteries that protected Marsaxlokk harbour, along with Fort Delimara seaward along Delimara point, Fort St Lucian on Kbira point in the middle of Marsaxlokk bay, Fort Benghisa on Bengħisa Point, and the Pinto and Ferreti batteries on the shores of Marsaxlokk Bay.

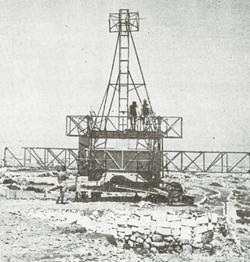

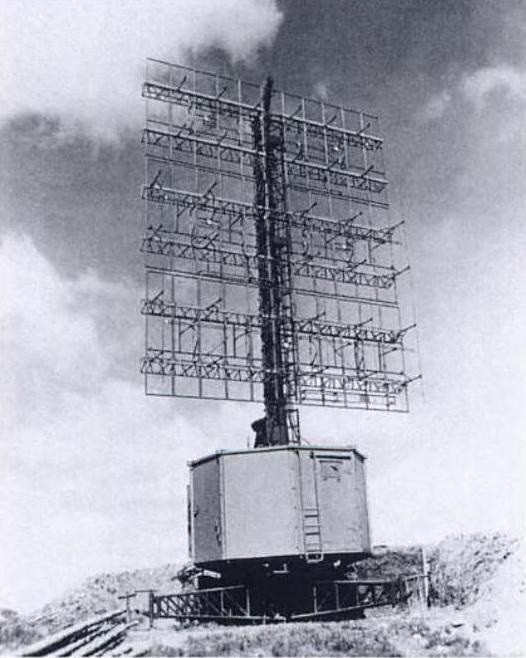

In the 50s the Fort was used by the RAF (100 Signals Unit). During this time the Camp mascot was a dog named Dodger. Later, Rusty, a dog and Scrubber a bitch were pets on the unit. Scrubber gave birth to 14 puppies, all of whom were found homes, elsewhere on Malta. One of the three Aerials on the camp was used in the film ‘The Malta Story’.

The fort is now used by “The Island Sanctuary” as a refuge for dogs.

Approximately 300 metres north of Fort Tas-Silg is the St Paul’s battery, a much smaller polygonal style fortification, that is in much worse repair.

St Paul’s Battery

St Paul’s Battery is a fortification that stands on high ground at the shoreward end of Delimara Point, above Il-Ħofra-z-Zgħira. It is a polygonal fort and was built by the British. It commands a field of fire northwards over St Thomas’ Bay and Marsaskala.

The fort is currently in very poor condition.

Approximately 300 m (980 ft) south is Fort Tas-Silg, a much larger polygonal style fortification.

Della Grazie Battery

Della Grazie Battery is a fortification by the British which stands above the shore to the east of Grand Harbour, close to Xghajra.

Construction started in 1888 and was completed in March 1893. The battery was constructed to take advantage of the improved breech loading guns then coming into service. It was equipped with two 6 inc and two 10 inch breech loading guns in disappearing mounts.

The installation takes the form of a polygonal fort, irregular hexagonal in plan, with two caponniers defending the forward ditches. Access to the fort is via a gatehouse and causeway across the rear ditch.

The battery takes its name from the much earlier Wignacourt tower, the Santa Maria delle Grazie Tower that stood close to the present battery. The original tower was demolished to clear the field of fire of the present battery.

The battery is now in the care of Xghajra council and is being restored to form the focal point for a public space, Battery Park.

The gallery below shows views on an anti-clockwise tour of the exterior of the fort. The rear section of the left hand ditch and the right half or the rear ditch are private property and inaccessible to photograph.

Fort Benghisa

Fort Benghisa is a fortification which stands on high ground on the seaward face of Benghisa point, the southern arm of Marsaxlokk Bay. It is a Polygonal fort and was built by the British.

The fort was the last polygonal fort built in Malta, built in 1909.

The gatehouse, and the shoreward ditch are in fair repair.

Fort Benghisa is one of a ring of forts and batteries that protected Marsaxlokk harbour, along with Fort Delimara and Fort Tas-Silg on Delimara point the north arm of Marsaxlokk Bay, Fort St Lucian on Kbira point in the middle of Marsaxlokk bay, and the Pinto and Ferreti batteries on the shores of Marsaxlokk Bay.

The fort is in private hands and the interior of the fort is inaccessible.

Victoria Lines

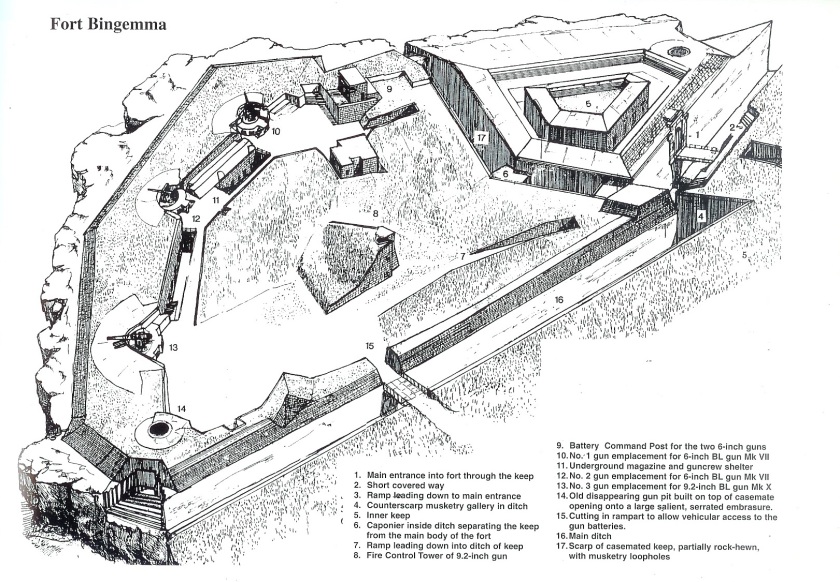

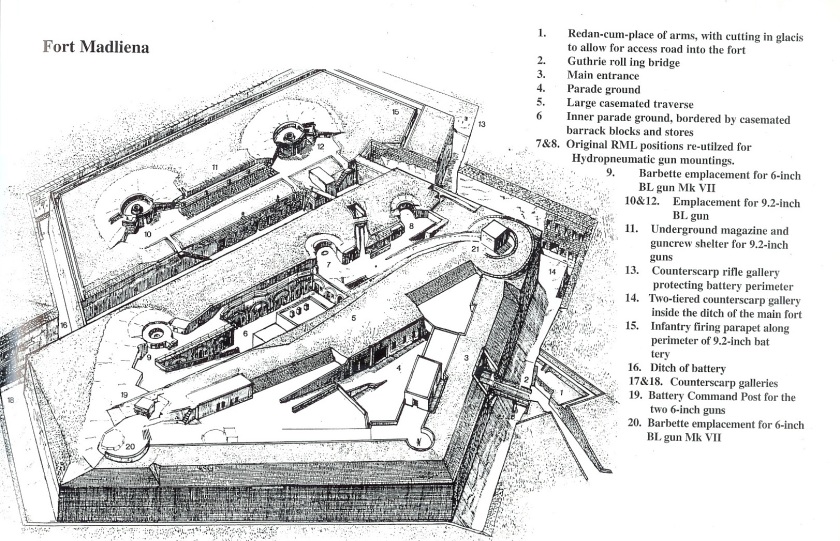

Including Fort Bingemma, Fort Mosta and Fort Madlena

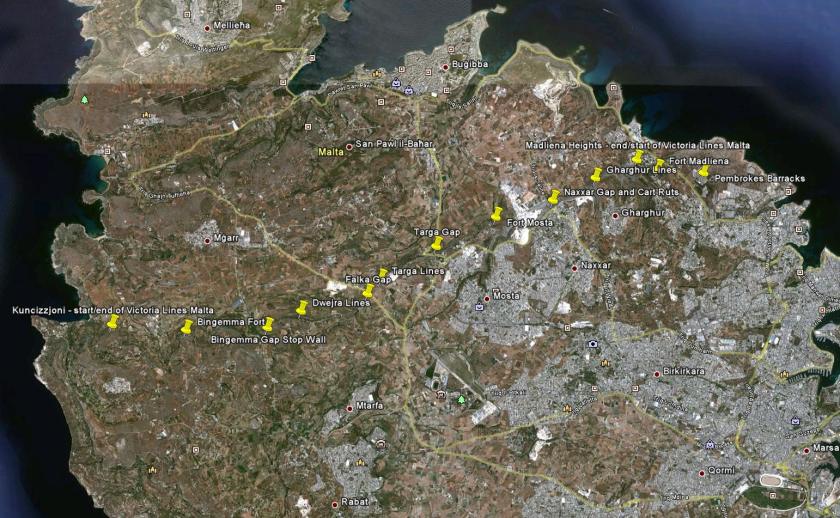

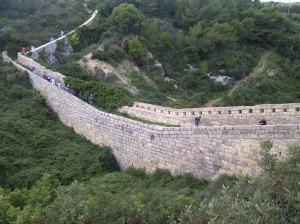

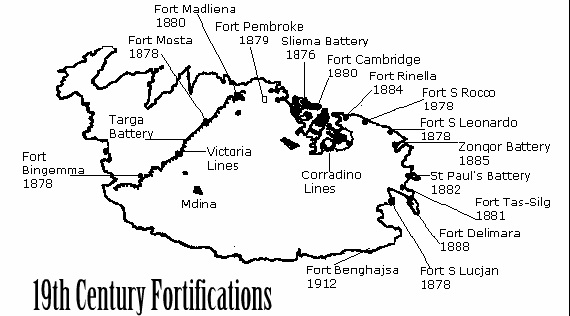

The Victoria Lines are a line of fortifications flanked by defensive towers, which spans 12 kilometres along the width of Malta, dividing the north of the island from the more heavily populated south.

The Victoria Lines are a line of fortifications flanked by defensive towers, which spans 12 kilometres along the width of Malta, dividing the north of the island from the more heavily populated south.

Location

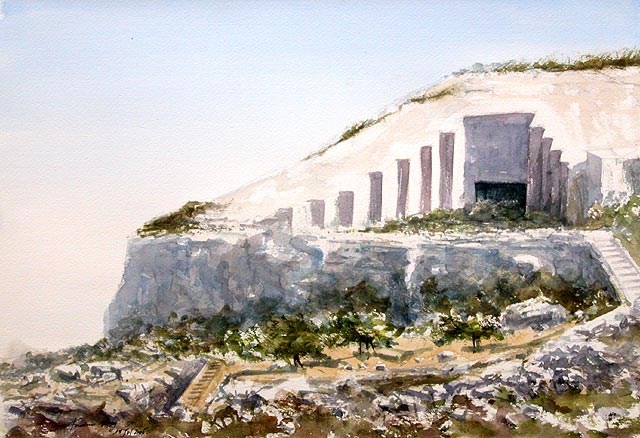

The Victoria Lines run along a natural geographical barrier known as the Great Fault, from Madliena in the east, through the limits of the town of Mosta in the centre of the island, to Binġemma and the limits of Rabat, on the west coast. The complex network of linear fortifications known collectively as the Victoria Lines that cut across the width of the island north of the old capital of Mdina was a unique monument of military architecture.

Background

When built by the British military in the late 19th century, the line was designed to present a physical barrier to invading forces landing in the north of Malta, intent on attacking the harbour installations, so vital for the maintenance of the British fleet, their source of power in the Mediterranean. Although never tested in battle, this system of defences, spanning some 12 km of land and combining different types of fortifications – forts, batteries, entrenchments, stop-walls, infantry lines, searchlight emplacements and howitzer positions – consitituted a unique ensemble of varied military elements all brought together to enforce the strategy adopted by the British for the defence of Malta in the latter half of the 19th century. A singular solution which exploited the defensive advantages of geography and technology as no other work of fortifications does in the Maltese islands.

The Victoria Lines owe their origin to a combination of international events and the military realities of the time. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, highlighted the importance of the Maltese islands.

Beginnings

By 1872, the coastal works had progressed considerably, but the question of landward defences remained unsettled. Although the girdle of forts proposed by Colonel Jervois in 1866 would have considerably enhanced the defence of the harbour area, other factors had cropped up that rendered the scheme particularly difficult to implement, particularly the creation of suburbs. Another proposal, put forward by Col. Mann RE, was to take up a position well forward of the original.

By 1872, the coastal works had progressed considerably, but the question of landward defences remained unsettled. Although the girdle of forts proposed by Colonel Jervois in 1866 would have considerably enhanced the defence of the harbour area, other factors had cropped up that rendered the scheme particularly difficult to implement, particularly the creation of suburbs. Another proposal, put forward by Col. Mann RE, was to take up a position well forward of the original.

The chosen position was the ridge of commanding ground north of the old City of Mdina, cutting transversely across the width of the island at a distance varying from 4 to 7 miles from Valletta. There, it was believed that a few detached forts could cut off all the westerly portion of the island containing good bays and facilities for landing. At the same time, the proposed line of forts retained the resources of the greater part of the country and the water on the side of the defenders; whereas the ground required for the building of the fortifications could be had far more cheaply than that in the vicinity of Valletta. Col. Mann estimated that the entire cost of the land and works of the new project would amount to 200,000, much less than that which would have been required to implement Jervois’ scheme of detached forts.

This new defensive strategy was one which sought to seal off all the area around the harbour within an extended box-like perimeter, with the detached forts on the line of the great fault forming the north west boundary, the cliffs to the south forming a natural, inaccessible barrier; while the north and east sides were to be defended by a line of coastal forts and batteries. In a way the use of the Great Fault for defensive purposes was not an altogether original idea for it had already been put forward by the Hospitaller knights in the early decades of the 18th century when they realised that they did not have the necessary manpower to defend the whole island. Then the Knights had erected a few infantry entrenchments at strategic places along the general line of the fault, namely, at Ta’ Falca and San Pawl tat-Targa, Naxxar. In fact, the use of parts of the natural escarpment for defensive purposes can be traced back even further, as illustrated by the Nadur watch-tower at Bingemma (mid-17th century), the Torri Falca (16th century) and the remains of a Bronze Age fortified citadel which once occupied the site of Fort Mosta (De Grognet).

This new defensive strategy was one which sought to seal off all the area around the harbour within an extended box-like perimeter, with the detached forts on the line of the great fault forming the north west boundary, the cliffs to the south forming a natural, inaccessible barrier; while the north and east sides were to be defended by a line of coastal forts and batteries. In a way the use of the Great Fault for defensive purposes was not an altogether original idea for it had already been put forward by the Hospitaller knights in the early decades of the 18th century when they realised that they did not have the necessary manpower to defend the whole island. Then the Knights had erected a few infantry entrenchments at strategic places along the general line of the fault, namely, at Ta’ Falca and San Pawl tat-Targa, Naxxar. In fact, the use of parts of the natural escarpment for defensive purposes can be traced back even further, as illustrated by the Nadur watch-tower at Bingemma (mid-17th century), the Torri Falca (16th century) and the remains of a Bronze Age fortified citadel which once occupied the site of Fort Mosta (De Grognet).

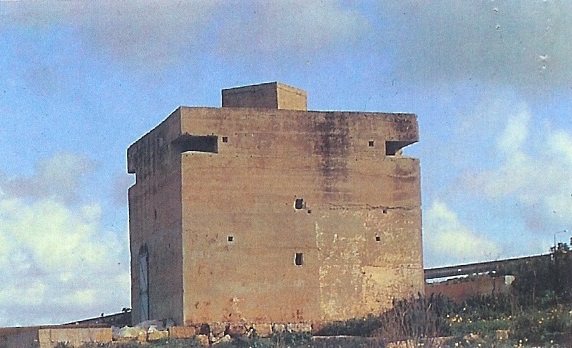

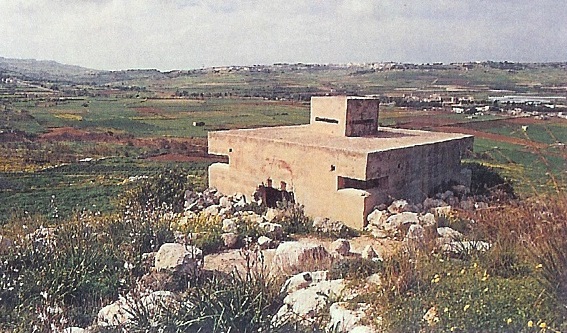

Building