Maltese Folk Music and Singing: Ghana

Traditional Maltese folk music has deep roots that date back to the 16th century, since music has always played an important part in the every day life of Maltese people.

Traditional Maltese folk music has deep roots that date back to the 16th century, since music has always played an important part in the every day life of Maltese people.

This type of local folk music is called ghana in Maltese.

It can safely be said that folk music in Malta was heavily influenced by its geographical location. In fact, researchers state that ghana is a combination of the famous Sicilian ballad mixed with Arabic tunes.

In the old days, visitors to the Maltese islands used to comment that they were very impressed with the Maltese people’s seemingly natural ability to sing and ryhme.

This folk singing was widespread on the islands and one could hear men and women singing while doing their daily activities on the farm, in the fields or around the house.

Ghana was in fact the music of peasants, fishermen and working class men and women.

A close look at the lyrics will reveal that each song usually recounts a story about life in the village or some important event in Malta history.

Street hawkers used to sing folk songs to attract attention to their products and declare how their products where better than the ones the seller next to them was selling! That’s traditional Maltese marketing!

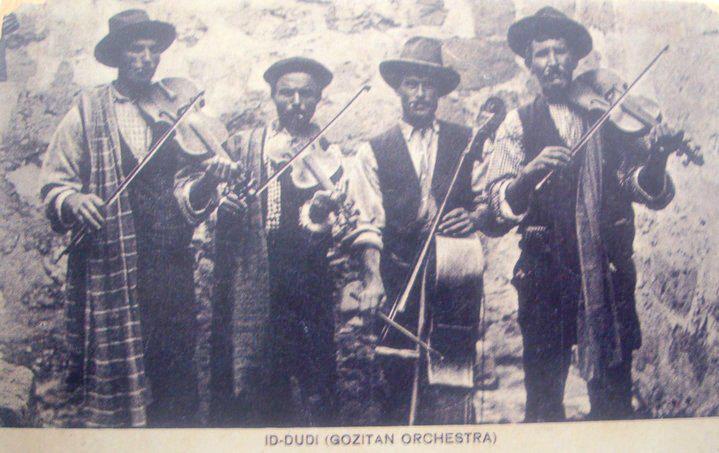

Nowadays the ghannej (meaning folk singer) is usually accompanied by three guitarists. However, in the old days there used to be other musicians accompanying the singer.

Types of Ghana

There are many types of Maltese folk singing but perhaps the two main categories are the following:

- Informal Għana

Throughout its history, informal għana situations frequently occurred amongst both men and women. The informal sessions shed light on the importance of the music in day to day life of the Maltese. The very origins of għana can be traced back to early peasant farmers. Ciantar (2000), in his article ‘From the Bar to the Stage’ puts together the writings of a number of foreign and Maltese scholars who make the claim early għana instances represents both the “simple life of the Maltese peasant life,” and the “intact natural environment of the island ”. Ciantar argues that the roots of għana are buried deep within traditional Maltese way of life, so much so that the two become synonymous with each other. Such a description by the scholar Aquilina (1931), for instance, emphasises this link between the people and għana:

How lovely it is, to hear from a remote and abandoned village amidst our island’s hills, during a moonlit evening, while the cricket is hidden among the tomato plants, breaking the evening’s silence, a handsome and healthy young man, swarthy as our country makes him, singing his għana ceaselessly. His soul would seemingly burst open with his singing!

Ciantar argues that these songs evoke the very roots of Maltese poetry and literature, a claim that is also supported by ‘Dun’ Karm Psaila, Malta’s national poet. In an article on the origin of Maltese poetry, Psaila goes on to link “għana to the modest recreation and aspirations of the common people.

Both scholars, Aquilina and Psaila, place għana in the ‘intact’ natural environment of the island:

…one could listen to għana songs, accompanied by a guitar or an accordion, sung by men and women on sea costs and during popular feasts such as Lapsi (Ascension Day). Youths used to sing għana love-songs in the open country, or the streets, or in houses during work-time.

Għana was a way to pass the time during hours of recreations and whilst completing household tasks. In particular, għana was practiced by the women singing on roof tops or in old communal wash houses, known as the għajn tal-ħasselin (“spring of the washers”). Wash houses were carved out of naturally forming caves around the island where water flows in a constant stream, providing a place to wash clothes. Like many other societies, men were the labourers and the women tended to the needs of the household. The women would converse with each other using rhyming song. It was a way of gossiping and passing time while they went about their household work. After washing, clothes were hung out to dry on the flat roofs typical of Maltese houses. From one roof it is easy to see – and indeed sing – across to neighbouring roofs over waist height fences. So essentially, there existed a pseudo community across the skyline of residential Malta, one in which women often took part in informal and unaccompanied għana sessions.

- Formal Għana

There are 3 main types of għana: fil-Għoli, tal-Fatt and Spirtu Pront. Għana fil-Għoli is also known as Bormliża, taking its name from the city of Bormla where it was popular. Bormliża singing requires males to reach into extraordinarily high soprano ranges without breaking into falsetto. This style mimicked the early informal għana sung by women, but due to its extreme vocal demands, this style is very seldom practised. Għana tal-Fatt literally means ‘fact’ or ‘actually happened’. This melancholic ballad style involves one għannej recounting a story about well known local identities, events or recent interesting or humorous, Maltese folktales and legends. Spirtu pront translates as ‘quick wit’, and originated from the informal ‘song duels’. Other types of għana are: bil-Qamsa and Makjetta

There are 3 main types of għana: fil-Għoli, tal-Fatt and Spirtu Pront. Għana fil-Għoli is also known as Bormliża, taking its name from the city of Bormla where it was popular. Bormliża singing requires males to reach into extraordinarily high soprano ranges without breaking into falsetto. This style mimicked the early informal għana sung by women, but due to its extreme vocal demands, this style is very seldom practised. Għana tal-Fatt literally means ‘fact’ or ‘actually happened’. This melancholic ballad style involves one għannej recounting a story about well known local identities, events or recent interesting or humorous, Maltese folktales and legends. Spirtu pront translates as ‘quick wit’, and originated from the informal ‘song duels’. Other types of għana are: bil-Qamsa and Makjetta

Spirtu Pront

In Spirtu Pront sessions, two or more għannejja (singers) are paired together and take part in an improvised song duel that demonstrates their knowledge of a wide range of social topics as well as their command of the Maltese language. Sessions take around an hour in duration, and there may be a number of sessions that make up a whole performance. The għannejja are the living poets of the Maltese language, singing in a highly expressive, free flowing style.

Their improvised melodic lines borrow heavily from Arabic influenced scales. Although improvisation is definitely an element, it is never the focus.

Once a session has commenced, għannejja must participate for the entire duration, and no new singer can join. The ghannejja usually begin with an introductory comment about who is taking part in the session. This section acts as a way of easing into the bout, but has more recently been used as a way of identifying participants during taped performances. The għannejja then begin discussing the topic. This would either be predetermined, or it will be established during the course of a session, just as a conversation would. Għana is not used to settle personal differences or arguments between singers. The song subjects themes themselves are dramatic and grave, even if dealt with wittily. They may be personal honour, reflections on social values, or political (in the narrow sense of the word) (Fsadni, 1993). Singers must display their superior knowledge in the topic, while adhering to a number of formal constraints. For instance, their improvised responses must rhyme, phrases should be in an 8, 7, 8, 7 syllabic structure, and singers must use ‘high-flown’ language. This form of language is not one that is used in ordinary social intercourse. It is highly elaborate making use of wit and double-entendre, and drawing on the many Maltese proverbs and idiomatic phrases. The Maltese language is a very ancient language, and compared to English, it does not contain many adjectives or adverbs. Instead, over the centuries, the Maltese have developed a rich and colourful library of proverbs to act as their descriptors. Occasionally, depending on the għannej, the language used overtly self-righteous. Ultimately, this type of practice creates tension between competing għannejja. In most cases, the għannejja would be shaking hands with their opponent, similar to a sporting match, showing that what they are saying is only for entertainment and they do not mean to cause any offence.

Once a session has commenced, għannejja must participate for the entire duration, and no new singer can join. The ghannejja usually begin with an introductory comment about who is taking part in the session. This section acts as a way of easing into the bout, but has more recently been used as a way of identifying participants during taped performances. The għannejja then begin discussing the topic. This would either be predetermined, or it will be established during the course of a session, just as a conversation would. Għana is not used to settle personal differences or arguments between singers. The song subjects themes themselves are dramatic and grave, even if dealt with wittily. They may be personal honour, reflections on social values, or political (in the narrow sense of the word) (Fsadni, 1993). Singers must display their superior knowledge in the topic, while adhering to a number of formal constraints. For instance, their improvised responses must rhyme, phrases should be in an 8, 7, 8, 7 syllabic structure, and singers must use ‘high-flown’ language. This form of language is not one that is used in ordinary social intercourse. It is highly elaborate making use of wit and double-entendre, and drawing on the many Maltese proverbs and idiomatic phrases. The Maltese language is a very ancient language, and compared to English, it does not contain many adjectives or adverbs. Instead, over the centuries, the Maltese have developed a rich and colourful library of proverbs to act as their descriptors. Occasionally, depending on the għannej, the language used overtly self-righteous. Ultimately, this type of practice creates tension between competing għannejja. In most cases, the għannejja would be shaking hands with their opponent, similar to a sporting match, showing that what they are saying is only for entertainment and they do not mean to cause any offence.

The accompaniment is provided by three guitars usually strumming Western influenced tonic to dominant chordal progressions. This gives għana a very unusual sound, not quite Eastern, but not quite Western. In between sung verses, the next għannej (singer) is given time to prepare a respond to his opponents’ remarks while the prim (first) guitar improvises melodies based on traditional għana melodies. The għana guitar is modelled on the Spanish guitar, and is described by Marcia Herndon as:

…a standard instrument, with metal frets and turning keys, metal strings, and traditional decorations on the front. It differs from the standard guitar only in that there are two sizes. The solo guitar is slightly smaller than the accompanying instruments. This, along with the method of tuning, indicates the presence in Malta of an older tradition of guitar playing which has almost died out elsewhere in the Mediterranean. The guitars are played with or without the use of a pick.

Prejjem

During spirtu pront, the “prim” begins improvising along a motive chosen from a ‘restricted’ repertory of Ghana motives. This section is known as the prejjem. These motives are popular, not only among the dilettante, but are well known outside of the għana community by the general Maltese public. The lead guitarist begins with an introductory section accompanied by the strumming of triadic, diatonic chords provided by the other guitarists.  As soon as the former completes his improvisation he joins the other guitarists in the accompaniment based on the tonic and dominant of the established key. The function of this introductory section is to establish the tonality and tempo for the session. Tonality changes from one session to another in a whole performance, depending on what collectively suits the għannejja (singers). In the most frequently used ‘La’ accompaniment (akkumpanjament fuq il-La), the strings of the lead guitar will be tuned to e a d’ g’ b’ e² while those of the second accompanying guitars will be tuned a minor third lower, except for the bottom string: e f# b e’ g#’ c#². The tone quality of these locally produced guitars is described by Ciantar (1997) as “very compact, with very low bass resonance” . Such tuning is through to better facilitate the technical demands imposed on the lead guitarist in the creation of new motifs and variations. In the introductory section a series of rhythmic and intervallic structures are created and developed; this same rhythmic and melodic material is then reiterated in the second section by both the ghannejja and the lead guitarist. The frequent use of syncopation and descending melodic movements, for instance, form part of the formal structure of both the singing and instrumental soloing in the spirtu pront; these are structural elements announced in the introductory section as to establish the style of both Ghana singing and playing.

As soon as the former completes his improvisation he joins the other guitarists in the accompaniment based on the tonic and dominant of the established key. The function of this introductory section is to establish the tonality and tempo for the session. Tonality changes from one session to another in a whole performance, depending on what collectively suits the għannejja (singers). In the most frequently used ‘La’ accompaniment (akkumpanjament fuq il-La), the strings of the lead guitar will be tuned to e a d’ g’ b’ e² while those of the second accompanying guitars will be tuned a minor third lower, except for the bottom string: e f# b e’ g#’ c#². The tone quality of these locally produced guitars is described by Ciantar (1997) as “very compact, with very low bass resonance” . Such tuning is through to better facilitate the technical demands imposed on the lead guitarist in the creation of new motifs and variations. In the introductory section a series of rhythmic and intervallic structures are created and developed; this same rhythmic and melodic material is then reiterated in the second section by both the ghannejja and the lead guitarist. The frequent use of syncopation and descending melodic movements, for instance, form part of the formal structure of both the singing and instrumental soloing in the spirtu pront; these are structural elements announced in the introductory section as to establish the style of both Ghana singing and playing.

Maltese Traditional Instruments

with special thanks to Anna Borg Cardona’s Website: Malta’s Musical Legacy

The ċuqlajta

The ċuqlajta is an instrument which on the Maltese Islands has very strong associations with Holy Week. Iċ-ċuqlajta encompasses a large number of different shapes and sizes of clappers and ratchets which produce their sound in different ways. Most are made totally of wood but a few are made of wood and metal or even out of Arundo donax reeds. One particular type of clapper has existed in Malta since Roman times and can still be seen in folk bands particularly in Gozo.

The ċuqlajta is an instrument which on the Maltese Islands has very strong associations with Holy Week. Iċ-ċuqlajta encompasses a large number of different shapes and sizes of clappers and ratchets which produce their sound in different ways. Most are made totally of wood but a few are made of wood and metal or even out of Arundo donax reeds. One particular type of clapper has existed in Malta since Roman times and can still be seen in folk bands particularly in Gozo.

Il-qarn

Another early, natural instrument is the horn, il-qarn or il-qrajna. Horns have long had protective properties on the Maltese Islands and for this reason were often placed over farmhouse doors to protect the inhabitants from the ‘evil eye’ of strangers arriving at the house. Cattle horns were also used as sound instruments when blown through a reed or reed and pipe (hornpipe). Horns were particularly associated with Carnival, suggesting a previous connection with spring ritual.

Another early, natural instrument is the horn, il-qarn or il-qrajna. Horns have long had protective properties on the Maltese Islands and for this reason were often placed over farmhouse doors to protect the inhabitants from the ‘evil eye’ of strangers arriving at the house. Cattle horns were also used as sound instruments when blown through a reed or reed and pipe (hornpipe). Horns were particularly associated with Carnival, suggesting a previous connection with spring ritual.

The bedbut

Simple whistles are commonly made out of corn or wheat stems and the Arundo donax reeds (Maltese qasab). These are known as il-bedbut, pl il-bdiebet. They were often made and used by children and then unceremoniously discarded. The bedbut, a down-cut single reed is made out of the Arundo donax plant and is also used as part of other more complex instruments.

Simple whistles are commonly made out of corn or wheat stems and the Arundo donax reeds (Maltese qasab). These are known as il-bedbut, pl il-bdiebet. They were often made and used by children and then unceremoniously discarded. The bedbut, a down-cut single reed is made out of the Arundo donax plant and is also used as part of other more complex instruments.

The żummara

Another very simple folk instrument is the mirliton or kazoo known in Malta as iż-żummara. This is made out of a section of Arundo donax reed into which a hole is drilled and on one end of which grease-proof paper is tied with string. One then hums a melody into the hole thus producing a rough raspy sound.

Another very simple folk instrument is the mirliton or kazoo known in Malta as iż-żummara. This is made out of a section of Arundo donax reed into which a hole is drilled and on one end of which grease-proof paper is tied with string. One then hums a melody into the hole thus producing a rough raspy sound.

The flejguta

Malta’s folk flute is known as il-flejguta. This is made out of a length of Arundo donax reed and is constructed on the principle of the penny whistle and recorder. It has a varying numbers of fingerholes.

Malta’s folk flute is known as il-flejguta. This is made out of a length of Arundo donax reed and is constructed on the principle of the penny whistle and recorder. It has a varying numbers of fingerholes.

The tanbur

The Maltese tambourine is known as it-tanbur in Malta and it-tamburlin in Gozo. It usually accompanies the bagpipe and other more recent instruments such as the accordion. The tanbur is made up of a round wooden brightly-coloured frame with a membrane tightly stretched on one side of it. It is known to have been of varying sizes, the largest reaching a diameter of about 60cm. It frequently has metal discs and pellet bells attached.

The Maltese tambourine is known as it-tanbur in Malta and it-tamburlin in Gozo. It usually accompanies the bagpipe and other more recent instruments such as the accordion. The tanbur is made up of a round wooden brightly-coloured frame with a membrane tightly stretched on one side of it. It is known to have been of varying sizes, the largest reaching a diameter of about 60cm. It frequently has metal discs and pellet bells attached.

Iż-żaqq

The Maltese bagpipe, known as iż-żaqq, is particularly important because it is not exactly like any other bagpipe. However, there are certain similarities, most strikingly with the Greek tsambouna. The Maltese żaqq is made out of the skin of an animal – generally of prematurely-born calf, but also of goat or dog. The complete skin is used including all four legs and tail. The chanter (is-saqqafa) is made up of two adjacent pipes, one with five fingerholes (left) and another with one (right). The chanter terminates with one large cattle horn.

The Maltese bagpipe, known as iż-żaqq, is particularly important because it is not exactly like any other bagpipe. However, there are certain similarities, most strikingly with the Greek tsambouna. The Maltese żaqq is made out of the skin of an animal – generally of prematurely-born calf, but also of goat or dog. The complete skin is used including all four legs and tail. The chanter (is-saqqafa) is made up of two adjacent pipes, one with five fingerholes (left) and another with one (right). The chanter terminates with one large cattle horn.

Thank you so much. I really agree with what the others said and it is also very handy for Maltese projects.

Anna Borg Cardona has just published a new book: “Musical Instruments of the Maltese Islands – History, folkways and tradition”.

Thank God for people like YOU who take the time to explore our heritage and share with everyone who LOVE their home land. I miss being there so much.

this is a very interesting site, our family’s who live around the world are going to love this. well done and thank’s for putting all this info,