The name Carnival originates from the Italian phrase ‘Carne vale’, which literally means ‘meat is allowed’ due to the fact that during the forty days of lent, meat consumption was not permitted in the Roman Catholic religion. This is why carnival is celebrated before the austerity of Lent.

The name Carnival originates from the Italian phrase ‘Carne vale’, which literally means ‘meat is allowed’ due to the fact that during the forty days of lent, meat consumption was not permitted in the Roman Catholic religion. This is why carnival is celebrated before the austerity of Lent.

In Christian countries, Carnival is the last opportunity to eat and make merry before Lent, the 40 day period of fasting in preparation of Easter and no wonder in Malta it is called Zmien ta’ bluha (‘a time of foolishness’), as it is characterised by all sorts of excesses and sometimes even rivalries that know no limits. Carnival is celebrated right before Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent. Mardi Gras means Fat Tuesday. But since the 13th century the popular festival started to be held even earlier. The Carnival season can now extend from right after Epiphany to the eve of Ash Wednesday.

But Carnival existed before Christianity, and its roots can be traced to its pagan forms which persisted well into the Christian era. Carnival floats also rolled in Babylon, in honour of the God Marduk, and in Egypt, for Isis, the queen-goddess of life and light, who opens the year. Elements of this Isis-cult persevered in early Christianity (Isis was even connected to Mary, mother of Jesus). They point to Carnival’s nature as a celebration of the waning of winter, the return of a new year, and fertility.

Other elements derive from the Roman Saturnalia, a festival with lots of food and drink, dress-up and parades. The social order was reversed and rules of behaviour were suspended: higher classes had no authority over the lower, masters waited on their slaves, men dressed like women. A temporary King was crowned and everyone had to abide by his most ludicrous whims. Even today, revelers elect a King Carnival.

Historically in Malta, this entertainment can be traced back to the early 1400s where we find the Universita’ issuing directives about the selling price of meat during carnival.

Encouraged by the Grand Masters of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem (1530-1798), Carnival declined in the 19th century but managed to live through the period of British rule (1800-1964) and has thus been handed down in an almost unbroken tradition of about six centuries.

Carnival seems to have been given a boost in Malta by Grand Master del Ponte in 1535. At that time carnival was all about knights entering tournaments and pageants. They proved their skills and were in turn awarded for that.

When the second Grand Master, Piero del Ponte, ruled in Malta carnival changed. He complained that some of the tournaments were getting the knights to be abusive, so he made it clear that he would no longer tolerate any wild or strange behaviour from the knights. He made sure that he was the only one that could approve the tournaments, and the other exercises that were necessary to train the Christian knights for their battles against the Turks.

Piero del Ponte wasn’t the only one who felt like the knights were exaggerating in their festivities. In 1560 Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette felt the same thing. He had already allowed the wearing of masks in public, even when this was forbidden for the rest of the year. He had also made the celebrations more fun. This is also the period where the floats started to be used. Only these weren’t on land as it is now, these were actually the decorated ships of the Order of St John.

Piero del Ponte wasn’t the only one who felt like the knights were exaggerating in their festivities. In 1560 Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette felt the same thing. He had already allowed the wearing of masks in public, even when this was forbidden for the rest of the year. He had also made the celebrations more fun. This is also the period where the floats started to be used. Only these weren’t on land as it is now, these were actually the decorated ships of the Order of St John.

In 1639 Grand Master Juan de Lascaris-Castellar issued an order, prohibiting women from wearing masks and costumes that would represent the Devil. Later those prohibitions were abolished. In 1730 we find the first parades on land. These were led by the Grand Master’s carriage and flanked by the cavalry marching to the beats of the drums. Behind them followed all the open carriages that were decorated by the people themselves. This was almost the same kind of carnival as we are celebrating it now.

Nowadays the Malta Council for Culture and the Arts organises the yearly carnival activities that are held during February over a period of 4 days. Folklore celebrations in Malta have, over time, included satirical forms of public rituals with massive public participation. Between 1972 and 1987 Carnival was held in May.

Nowadays the Malta Council for Culture and the Arts organises the yearly carnival activities that are held during February over a period of 4 days. Folklore celebrations in Malta have, over time, included satirical forms of public rituals with massive public participation. Between 1972 and 1987 Carnival was held in May.

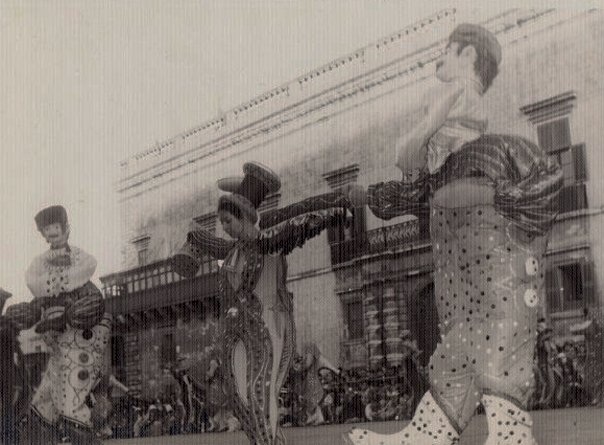

During the carnival days, Valletta bursts at the bastions with phosphorescent carnival floats. These floats are the mainstay of the Maltese Carnival. Massive cardboard structures, painted in an explosion of screaming colours, start their route at Floriana on the outskirts of the capital, enter Valletta’s main entrance, then commence a slow parade through the principal streets. The “city built for gentlemen” turns into the City of Fools for the carnival days. Prizes are awarded for the best artistic dances, costumes, floats and grotesque masks. Before the Second World War, the floats often represented local political figures. In the 1920s and 30s the caricature of political figures often led to tense situations that induced the Government to ban such customs from future editions of Carnival. This ban lasted until 2013 when it was realized that there were no such laws in the Maltese Legislature that restricted carnival floats depicting political satire. In fact for the 2013 Carnival edition there was one float which depicted some mild political satire. The Maltese Carnival does not, however, consist only of these floats. Throughout the five days of merrymaking, numerous activities take place throughout the island.

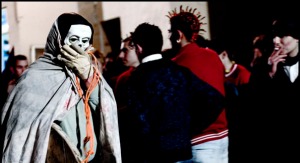

Carnival in Gozo is a separately organised edition of the festivity. These festivities were first officially organised in Gozo in the year 1952. The Gozitans have their own floats and parades. The main activities take place in It-Tokk, the main square in Gozo’s capital Victoria, and in Nadur square. The Gozitan Carnival bears witness to a separate and autonomous interpretation of the festive occasion and is therefore instilled with a character of its own, stemming from the different temperament of the people who set it up. But a parallel event, which takes place in Nadur, defies the official definition of a standardised Carnival activity such as those held in Valletta and Victoria. The novelty of the Grotesque Carnival on Nadur is that there is no organising committee to plot out its course.

Carnival in Gozo is a separately organised edition of the festivity. These festivities were first officially organised in Gozo in the year 1952. The Gozitans have their own floats and parades. The main activities take place in It-Tokk, the main square in Gozo’s capital Victoria, and in Nadur square. The Gozitan Carnival bears witness to a separate and autonomous interpretation of the festive occasion and is therefore instilled with a character of its own, stemming from the different temperament of the people who set it up. But a parallel event, which takes place in Nadur, defies the official definition of a standardised Carnival activity such as those held in Valletta and Victoria. The novelty of the Grotesque Carnival on Nadur is that there is no organising committee to plot out its course.

Every year, there is the so-called Il-Parata, a re-enactment in dance form of the 1565 struggle between the forces of Maltese and Knights of St John against those of the Muslim Turks.

Every year, there is the so-called Il-Parata, a re-enactment in dance form of the 1565 struggle between the forces of Maltese and Knights of St John against those of the Muslim Turks.

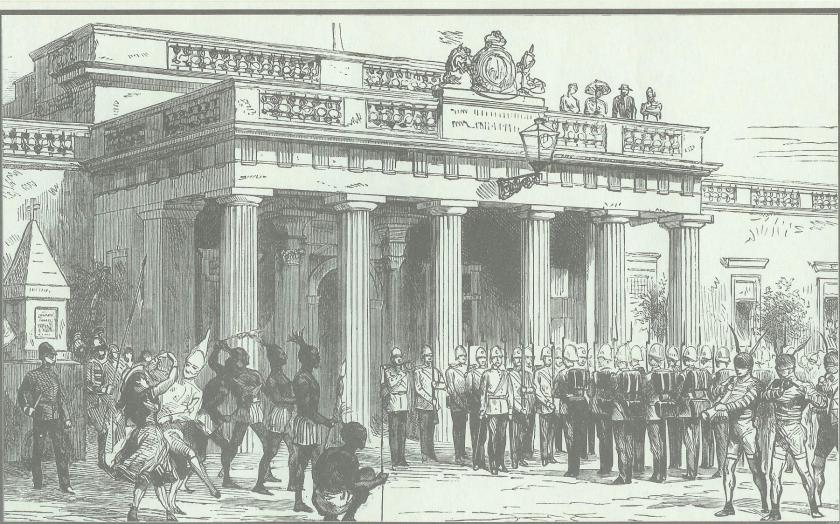

During the Knights, the Parata was taken very seriously both by the Knights and the people in general as its part was of special historical significance. It was the custom for some farmers and country folk and later carnival companies of young dancers to gather early under the balcony of the Grandmaster’s Palace eagerly waiting until they received formal permission from him to celebrate Carnival. When the sign was given, the companies dressed as Christians and Turks performed a mock fight re-enacting the Great Siege of 1565. Under the Knights it was taken very seriously, and the Maltese eagerly awaited its performance because the rule was “no Parata, no Carnival”.

Nowadays it is mainly children who participate in the dance. The Parata is of special significance in the history of the Maltese Carnival.

Grand Master Zondadari introduced the traditional game Kukkanja (Cockaigne) in 1721. A crowd assembled in the Palace Square on Carnival Monday and at a given signal attacked the hams, sausages and live animals tied to the long beams fixed against the guard house and covered over with branches of trees in leaf. The provisions became the property of those who, having seized them, were able to carry them off in safety through the crowd.

On the evening of 11 February 1823, the last day of Carnival, 110 boys aged 8 to 15 yrs were trampled upon as they were leaving the convent of the Minori Osservanti at Strada St Ursula Valletta.

On the evening of 11 February 1823, the last day of Carnival, 110 boys aged 8 to 15 yrs were trampled upon as they were leaving the convent of the Minori Osservanti at Strada St Ursula Valletta.

It was customary during Carnival to entertain a large number of children at the convent, but as they were leaving down a corridor, an exit door was left shut, and the pressure from behind crushed and suffocated the children. The Royal Malta Fencibles helped to deal with the aftermath of the disaster.

There was another incident on 22 February 1846 which could have had tragic consequences but thankfully was avoided by a whisker.

This 1846 incident was more of a tragic comedy as the Governor of the time, Sir Patrick Stuart did not allow people to wear masks on Carnival Sunday and this was met with much disgruntlement from the Maltese people. The people decided to dress up their horses, mules, donkeys, dogs and other animals instead to parade them in Valletta. During this time feelings between the British Protestant and the Maltese Catholic population were strained and since some of the Maltese dressed up their animals in the guise of Protestant clergymen, this irked the British. The matter reached boiling point when some Maltese youngsters assaulted bandsmen of the 42nd Highlanders. A.E Abela quotes Rev. Henry Seddall’s book: Malta, Past and Present (1870), where he wrote: “If the order had been given to them (the Highlanders) to disperse the mob… torrents of blood would probably have been shed.”

Carnival 1929 started on Saturday 9 February up to Tuesday 12 February. The programme started off with a Maltese Parata from 7am to sunset. The Parata ushered in Carnival.

Carnival 1929 started on Saturday 9 February up to Tuesday 12 February. The programme started off with a Maltese Parata from 7am to sunset. The Parata ushered in Carnival.

The following day the Maltese Parata took part again from 8am to noon followed by a defile’ and competition of schoolboys and other boys’ associations. In the afternoon, King Carnival arrived followed by a defile’ and competition of companies in costumes and then Grotesque Marches. The following day a defile’ and competition of triumphal cars was organised and a defile’ and competition of Decorated Motor Cars. Dancing and Figure Displaying Competition by held at Piazza S. Giorgio at 3.45 pm followed by a continuation of the Grotesque Marches Competition. The day was wrapped up with a Venetian March.

Just like all Carnivals under British rule especially in the 19th century and early 20th century, Carnival 1929 parades, was famous for their biting satirical themes and many of the intricate floats were designed to poke fun at political figures and unpopular government decisions; however, political satire was essentially banned as a result of a law passed in 1936.

The last day of Carnival 1929 consisted of a farewell Parade of King Carnival, the last Parade of Companies in Costume, a continuation of Grotesque Marches competition and a Pyrotechnical Display on Piazza S. Giorgio. The Pyrotechnical display consisted of:

• Aux Flambeaux

• Magic Lightening

• Niagara Falls

• Roman Candles Display

• Revolving Stars

• Departure of King Carnival on Airship ‘Ramadan’

Carnival parades during the British period, especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries, were noted for their biting satirical themes, and many of the intricate floats were designed to poke fun at political figures and unpopular government decisions.

In the 1920s and 30s the caricature of political figures often led to tense situations that induced the Government to ban such customs from future editions of Carnival. Political satire was essentially banned as a result of a law passed in 1936.

Prizes are awarded for the best artistic dances, costumes, floats and grotesque masks. The Maltese Carnival does not, however, consist only of these floats. Throughout the five days of merrymaking, numerous activities take place throughout the island.

Up to the early 1970s Carnival was held at St George Square in Valletta

Up to the early 1970s Carnival was held at St George Square in Valletta

From early 1970s the hub of the organised activities was in Freedom Square, where a stage and seating used to be specially erected for open-air performances of dance, drama and song. This arrangement had to stop when the new parliament building project started in 2011. Freedom Square has been taken by the new parliament building. Carnival in 2012 was held at the Valletta Bus Terminus and in 2013 it was held at the Floriana Granaries.

Carnival was held at Freedom Square till 2011

Carnival was held at Freedom Square till 2011

Carnival 2012 was held at the Bus Terminus

Carnival 2012 was held at the Bus Terminus

Carnival 2013 was held at the Granaries

Carnival 2013 was held at the Granaries

Carnival 2014

Carnival 2014 saw the return of a number of elements which were not included in the previous editions for a number of years.

Carnival 2014 saw the return of a number of elements which were not included in the previous editions for a number of years.

For the first time in 40 years, Carnival was held in St George’s Square, bringing the festive atmosphere to the heart of the capital, where it was held up to the early 1970s. Between 1972 and 2011 the hub of the organised activities was in Freedom Square, but this was stopped when the new parliament building project started in May 2011. The year after, Carnival was held at the Valletta Bus Terminus while in 2013 it was held at the Floriana Granaries.

The return of satire, too, was a novelty with its roots buried in the past. Carnival parades during the British period, especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries, were noted for their biting satirical themes, and many of the intricate floats were designed to poke fun at popular figures and unpopular government decisions. In the 1920s and 1930s the caricature of political figures often led to tense situations that induced the Government to ban such customs from future editions of Carnival.

The qarcilla or wandering farce – which also made a return in 2014 – was still held in the Valletta Carnival up to the early 20th Century. A man dressed as a notary read out a marriage contract in rhyming verse full of witticisms – some verging on the obscene – to a bride and groom.

Kitba taz-Zwieg ta’ John u Virginia – 2014 Qarcilla

by Trevor Zahra

The first known qarcilla was written for the 1760 Carnival by the poet Fr Felic Demarco. The 2014 qarcilla, penned by Trevor Zahra, was performed by a number of actors, including Joseph Galea. They wandered around the streets of Valletta on Saturday evening, re-enacting a parody of a wedding ceremony.

Also on Saturday evening Carnival festivities reached their climax. In the Carnival edition of 2014 – another first – festivities ran through the night, in a non-stop celebration.

Yet another first was the twinning with Notting Hill Carnival, Europe’s largest festival of popular culture. A Caribbean Carnival in Britain – Notting Hill Carnival, takes place on the streets of North Kensington in London with elements that include musical bands, sound systems, masquerade bands, singers, musical and artistic competitions, Caribbean food stalls, street fashion, sound stages and dancing spectators following bands through the streets. The Notting Hill Carnival attracts on average of 1.5 million people over its two days in August each year.

Past Carnival and New Year’s Eve Drama in Malta

by G Mifsud Chirchop

Sureya John, the UK Universal Carnival Queen, headlined the first ever presentation of the Notting Hill Carnival in Malta. Another Carnival Queen, from the Elimu Paddington Band, also performed with the Notting Hill Group.

And to highlight that Carnival is all about diversity and inclusion – and, ultimately, joining in the fun – in 2014 a group of dancers from the Adult Training Centres of Agenzija Sapport presented a dance at the National Carnival. Other novelties included the artistic direction by Carnival director Jason Busuttil for the first time, a People’s Choice Award which was selected by televoting.

Apart from the above, there were also dance competitions, float defilés, swarming streets and exuberant costumes that are so much a part of Carnival. For a few days Valletta was in party mode. Streets were transformed, children everywhere were in fancy dress, gigantic floats pushed their way through the crowds.

In Gozo the traditional and spontaneous Carnival in Victoria hosted various traditional folklore groups. The old streets of Gozo’s capital city were given a breath of fresh air with the sound of music played by guest musicians and other folkloristic groups in traditional colourful costumes. Among the leading artists performing in Pjazza San Gorg, featured ‘Gorg il-Puse’ who enchanted the public with his violin playing. In Independence Square a group of Maltese and Gozitan folk singers, known as ‘ghannejja’ and guitarists, entertained the audience present with their spontaneous folk music known as ‘l-ghana.’ The children’s carnival was held in Independence Square. Seven schools coming from six different Gozitan villages participated in this children’s carnival, following the Ministry for Gozo`s initiative to double the school funding so as to encourage increased children’s participation. The extravagant parade themed ‘Gozo: Colours, Life and Extravagance,’ organised for the first time by the Ministry for Gozo under the artistic direction of Felix Busuttil was held in Republic Street in Victoria. The organised Carnival in Gozo dates back to 1952.

Hundreds jammed the streets around Nadur Church on Saturday evening to celebrate Carnival, although the weather also appeared to have kept many people away. As in previous years, a wide variety of costumes were on show, with the local focus being very much on the passports for sale controversy.

The Malta Carnival is organised by the Malta Carnival Committee with the support of the Malta Council for Culture and the Art. For the full Carnival 2015 programme visit maltaculture.com